History is littered with sporting dynasties – in basketball, Phil Jackson’s Chicago Bulls are often touted as one of the all-time greats; in rugby, it’s New Zealand’s fearsome All Blacks who reign supreme. Of equal significance to both is a group of female volleyballers from the East, whose exploits have sadly been underreported in recent years.

In the early 1960s, the world of women’s volleyball was dominated by the Nichibo Kaizuka team, consisting largely of textile workers from the outskirts of Osaka. Under the rigorous training regime of coach Hirofumi “The Demon” Diamatsu, this band of young women annihilated their domestic opponents, eventually being selected to represent Japan internationally against other, higher-ranked teams.

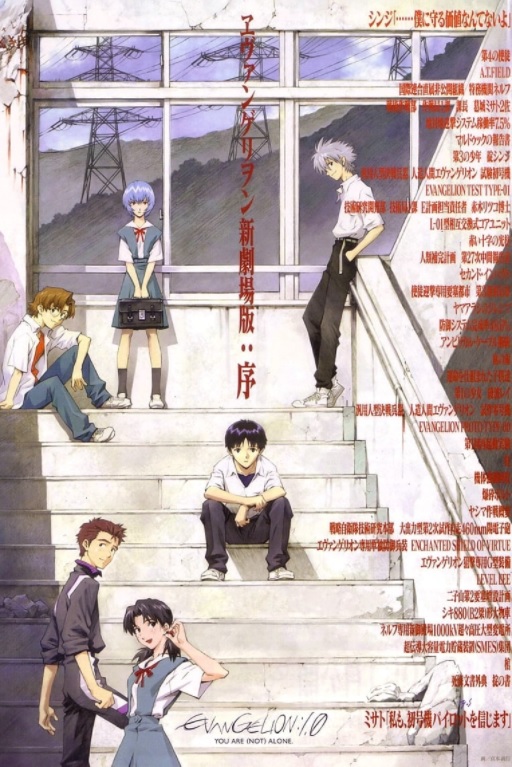

Diamatsu’s team would go on to be dubbed the “Oriental Witches” by the foreign press, owing to their athletic prowess and unparalleled succession of victories – 258, to be exact. This extraordinary feat saw the Japanese players become celebrities at home and abroad, inspiring cartoons, comics, and documentaries such as this one, albeit without the same levels of artistry and reflection.

The Witches of the Orient comes from French documentarian Julien Faraut, who three years ago examined the psyche of tennis player John McEnroe in another MIFF entry, In the Realm of Perfection. Much of Faraut’s narrative is composited of existing footage – including the aforementioned cartoons, plus material of the team competing in Eastern Europe – which is then paired with electronic music, an eclectic combination that leaves the viewer in a trance.

Perhaps the most mesmerising sequence of Witches is the archival film of the women training in Kaizuka. In this footage, coach Diamatsu can be seen relentlessly spiking balls at his players to ostensibly improve their return serve, forcing them to sprint and roll across the court until they are all but exhausted of energy. While Diamatsu’s arduous techniques are somewhat mortifying to witness, they do provide an indication as to why the Witches were so competitive.

Faraut’s story also draws upon interviews with Nichibo Kaizuka’s surviving members, who provide rare, exclusive access to their lives. The women never speak directly to the camera, instead providing voice-overs that are matched to their daily routines – the earliest example being Katsumi Chiba and her morning workout at a local gym – as well as a discussion between them over dinner.

There are some real gems offered in the ladies’ narration and B-roll of their activities. Yoshido Kanda speaks most candidly of all the former players, reflecting upon her status as a substitute player and why the women were so drawn to Diamatsu despite his gruelling nature; meanwhile, Yoko Tamura’s footage has a lifestyle to be envied, shown playing a game of memory with her grandchildren and watching volleyball anime with her family.

Although the narrative is transfixing, Witches would benefit from some tighter editing – the montages are too long at times, and there’s a sequence about the players’ nicknames that adds nothing to the story. There are some questionable stylistic choices too, with Faraut keeping a tight 4:3 frame throughout – even in contemporary settings – only to inexplicably transfer to a widescreen ratio in the third act.

Watching The Witches of the Orient, it’s difficult to fathom why their achievements have been so muted in contemporary media. The Nichibo Kaizuka story may not possess the drama or excitement of other sporting dynasties, but their winning streak is yet to be matched by any other volleyball team, as is the level of fame and fervour they generated overseas. Surely those facts alone are worth a place in sporting folklore.

Crafted with an element of idiosyncrasy, Julien Faraut’s The Witches of the Orient is a beguiling story about a group of women whose triumphs ought to be celebrated more. The openness and humility of the subjects is what charms most, though the mesmeric visuals play their part too.

The Witches of the Orient is currently streaming as part of the Melbourne International Film Festival on MIFF Play until August 22nd.