In recognition of The Boy and The Heron releasing nationwide this very week, our resident animation buff Tom Parry is here to list its director’s filmography from least best to absolute best — because there is no such thing as a bad Miyazaki picture! But first, an explainer…

With the exception of Walt Disney, there is indisputably no animator more famous or revered than Hayao Miyazaki. In a career spanning six decades, the Japanese auteur has left an indelible mark on the artform through his distinctive films, readily identified by their gentle tone, strong female characters, fantasy themes, pertinent morals and gorgeous illustrations.

His work has spawned plenty of imitators and thousands more admirers, both within the industry and outside of it — all of his feature-length pictures have an average rating of 3.95 stars or above on Letterboxd, plus an approval rating of 87 percent or above on Rotten Tomatoes. He’s garnered no shortage of accolades either, including Berlin’s Golden Bear, numerous Annie Awards, and two Oscars — one competitive, one honorary.

Miyazaki-san is also notorious for prematurely exiting the industry, having declared retirement in the late 1990s, 2013, and again in 2018, only to return to directing each time, hence earning himself a reputation as the John Farnham of Cinema. He pulled the same trick just this year, announcing he has another project in the works despite previously saying that The Boy and The Heron (2023) would be his last as a director.

That title is finally reaching local cinemas this week, and to celebrate this momentous occasion, yours truly is taking a look back at Miyazaki’s previous 11 releases and determining which of his releases is best. Of course, all of his pictures are fantastic, which makes ranking his filmography a nigh-on impossible task; if nothing else, consider this list a guide for which of the living legend’s masterpieces to prioritise seeing before his latest one.

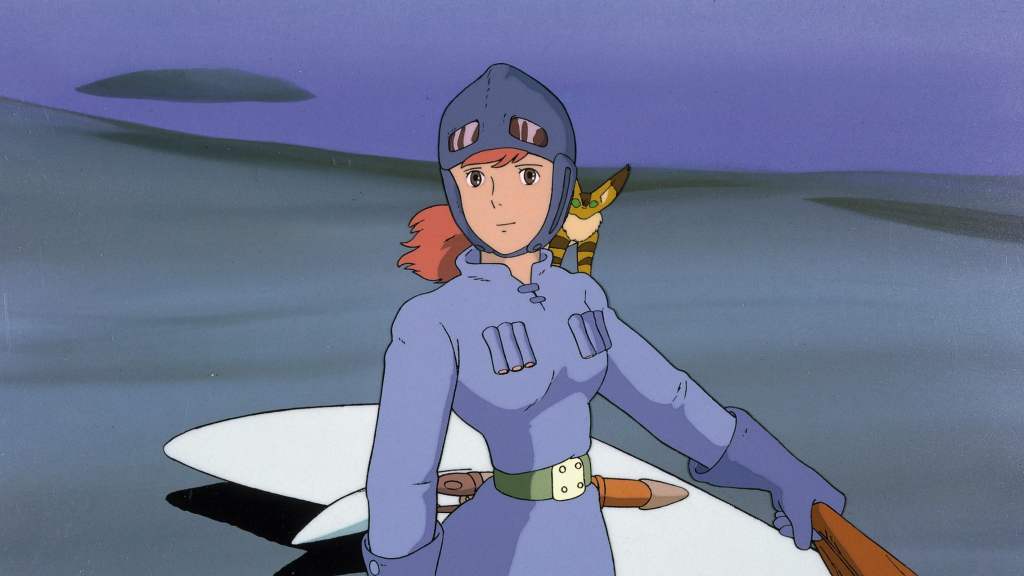

11. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

One of the earliest directorial efforts from Miyazaki, and it shows — but it’s certainly not without charm. Nausicaä follows its eponymous heroine, a teenage princess of a post-apocalyptic land, who seeks to protect a neighbouring jungle and its large insectile inhabitants from a warring kingdom, one seemingly hellbent on the forest’s destruction.

This feature, the second to be helmed by Miyazaki, can be considered the genesis for the themes which would later come to define his catalogue. Its screenplay touches upon themes of conservation, pacifism and anti-Imperialism, all tropes which have come to be a consistent presence in his career, while also drawing upon his penchant for aviation and placing a brave, resourceful young woman in a leading role.

Yet it’s not without flaw. The screenplay is too reliant on dialogue to tell its story; the score of Joe Hisaishi — in the first of his many collaborations with Miyazaki — utilises electronic instruments at times, which prove tonally jarring; and the illustrations lack detail, being near-indistinguishable from other anime projects of the period. (In fairness, the film was produced on a limited budget.) Nausicaä may be considered a classic, and rightly so, but to consider it Miyazaki’s best is doing the remainder of his works a great disservice.

10. Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)

Countless productions have paid tribute to Miyazaki, but here is a rare instance in which the director pays homage to himself. Adapted from British author Diana Wynne Jones’ novel of the same name, its plot concerns a young woman who is cursed with an elderly body, the wizard who offers her refuge, and the moving, mechanical fortress which they call home.

Howl’s Moving Castle plays like a melange, or even a rehash of all the Miyazaki films released up until that point, sharing many of the themes and even the same aesthetics as those made previously. This, in turn, marks the picture as the least distinctive and least memorable of his career.

Yet the film is not without appeal. The characters are all likeable and well-written, the orchestrations of Hisaishi beautiful and the illustrations, as ever, stunning to look at. It’s a less-than-stellar glint in his resumé, sure, but certainly not bad. Heck, compared to most other animated features, it’s exceptional.

9. Ponyo (2008)

For a film-maker unafraid to place mature and complex themes into his stories, Ponyo appears a retrograde step for Miyazaki-san; it takes place in a contemporary setting, has two kindergarten-aged children as its core protagonists, and borrows heavily from a Danish fairy-tale that has been told countless times elsewhere. The only difference being, this Little Mermaid’s dream of becoming human could lead to an ecological catastrophe. Now there’s a twist!

Despite being a definite contender for the cutesiest and most juvenile product in this list, it’s impossible not the be charmed by Ponyo, nor its namesake character — her insatiable enthusiasm for the human world and its delicacies is the undoubted highlight. Pleasing further is a driving sequence that evokes Miyazaki’s earliest cinematic handiwork (more on that later) and rich use of colour throughout; less so a nauseating theme that accompanies the English dub, and the heavy-handed application of its environmentalist themes.

Anime purists may scoff at its soft tone and simplistic messaging, but those apparent misgivings are what makes the title ideal for a younger audience, or those needing an easy entry point to Japanese animation.

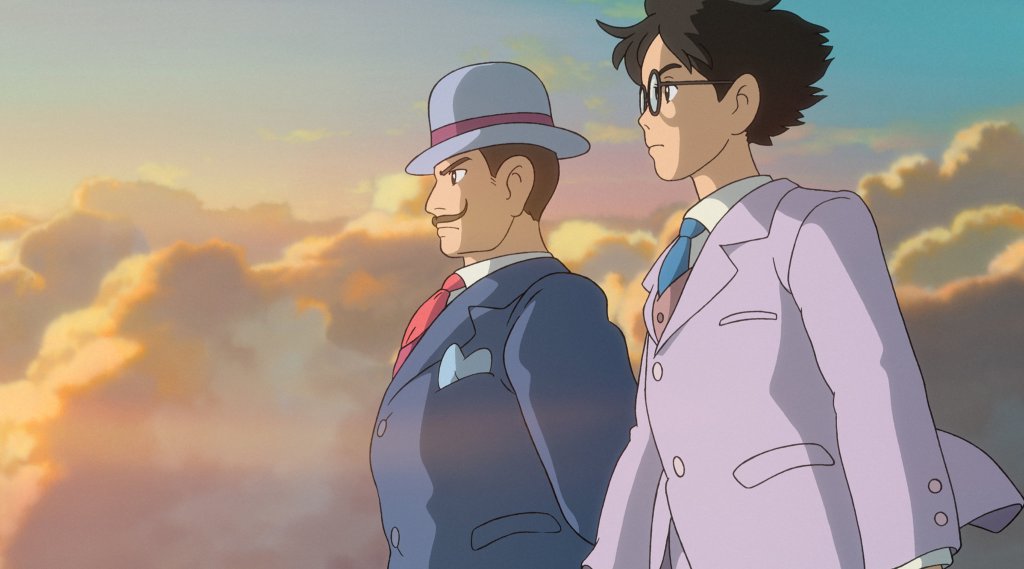

8. The Wind Rises (2013)

Biographical stories aren’t typically the domain of animators; then again, Miyazaki isn’t your typical animator. This one recounts the life of inventor, aviator and engineer Jiro Horikoshi — infamous for developing the Mitsubishi “Zero” fighter planes that fought during World War II — tracing his journey from teenagehood to immediately after the Japanese surrender, revealing himself to be an idealistic dreamer.

The Wind Rises ties firmly with two of Miyazaki’s persistent motifs: his fondness for aviation, and his unwavering advocacy for pacifism. It’s the former which comes through most strongly, courtesy of the mesmeric flying scenes, Jiro’s dream sequences, and the human sound effects applied to the aircraft that assist in personifying them. And, of course, the animation and music are exquisite.

Sadly, there are flaws. The film does romanticise its main protagonist somewhat, who lacks complexity and doesn’t appear particularly distressed by his aircraft being utilised for warfare; and some of the minor characters present themselves more like caricatures than they do human beings.

7. Castle in the Sky (1986)

Properly considered the first movie to hail from Studio Ghibli — the world-renowned animation firm co-founded by Miyazaki, fellow director Isao Takahata, and producer Toshio Suzuki — and a captivating one at that. Its story is about a young girl and boy in possession of a powerful crystal, who travel across their homeland in search of a mythical flying kingdom known as Laputa.

There are numerous signs of a director transitioning into an auteur in Castle in the Sky, as Miyazaki again applies his themes of environmentalism, nonviolence and aviation to the screenplay. Other connections to his future output are also present, such as the steampunk visuals that would later be applied to Howl’s Moving Castle.

Even so, parts of this picture clearly indicate a career still in its infancy. The script is rather dialogue-heavy, much like Nausicaä, breaking the medium’s golden rule of “Show, Don’t Tell”; the moods of the supporting characters are rather capricious; and it doesn’t quite reach the level of storytelling magic for which Studio Ghibli is nowadays famed for.

6. My Neighbour Totoro (1988)

Undoubtedly the sweetest, cutest and most innocent feature to be directed by Miyazaki. Here, the plot unfolds in rural Japan, where a mother-of-two is recuperating from an undisclosed illness; nearby lives her husband and their two daughters, who occupy their time by playing in the adjacent forest. It’s in this same forest that the girls encounter a series of friendly beings — including a large grey one whose name graces the title.

Chief to the appeal of Totoro is the ingeniously-designed creatures who interact with Satsuki and Mei; this includes Totoro himself, who would go on to be incorporated into Studio Ghibli’s logo, and become the company’s official mascot. Also notable is the picture’s tone, which is light and palatable to even the youngest of viewers, possessing very little in the way of threat or conflict.

And therein lies Totoro’s biggest problem: this slice-of-life drama is too light and fluffy for its own good. The only tension that occurs is when Satsuki learns of her mother’s deteriorating health, leaving her angry and causing her to yell at her younger sister, and even that low level of friction is resolved in a matter of what feels like seconds.

5. Princess Mononoke (1997)

Quite possibly the most mature and complex work of this list, and one often rated highly in animation circles. Its title refers to a female warrior raised by wolves, who seeks to protect the forests she calls home in feudal-era Japan. But she is not the central figure in this tale. Instead, the lead protagonist is a young prince who seeks to stop the demons that are terrorising his village.

Mononoke’s tone is noticeably darker than all other Miyazaki pictures, as evidenced by the amount of violence and blood on display; it also leans heavily into its conservationist, pacifist and anti-imperialist themes. Additionally, the film possesses characters that are well-written with intricate personalities; and what may well be Hisaishi’s best score, at times evoking the work of his American contemporary, Howard Shore.

As for problems, having the narrative follow Prince Ashitaka — as noted above — means less attention is paid to San, who is by far the more interesting of the duo; and the conclusion isn’t wholly satisfying. Those flaws aside, there’s very little to complain about.

4. Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

Another literary adaptation, and one of Miyazaki’s better examples. Beginning with its heroine, a young witch, leaving her home to partake in an adolescent rite-of-passage, the story eventually settles in the town of Koriko, where our broomstick-riding maiden comes to find employment at a bakery in exchange for a place to stay.

Like Totoro before it and Ponyo after it, Kiki has a sweet, inoffensive tone that makes it perfect viewing for youngsters, or those otherwise unfamiliar with anime. But where Totoro is largely devoid of conflict, Kiki has its central protagonist undergo a great emotional struggle; and where Ponyo talks down to its audience with simplistic messaging, Kiki has faith in their intelligence and maturity.

And then there’s the wonderful flying sequences, and the immensely likeable characters, and the European aesthetics, all of which combine with the usual Miyazaki hallmarks to make a fun, heart-warming adventure. If there’s any fault with Kiki, it lies in the somewhat rushed conclusion, and the convenient amount of time its witch takes to overcome her woes.

3. Porco Rosso (1992)

This one is quite the achievement; not only does it contain a Flying Pig as the main character, but it manages to overcome its rather silly premise to be a funny, heartfelt and mesmerising tale. It’s a tale that sees Marco — a veteran of the First World War who has gone on to become an aerial bounty hunter — partner with an aspiring female mechanic to defeat his American arch-rival, Curtis, and the shenanigans that ensue.

Predictably, yet pleasingly, Miyazaki’s love of aviation shines through in Porco Rosso, with detailed illustrations of aircraft and enchanting moments of planes in flight; also emerging strongly is his steadfast objection to Imperialism, with the film’s titular protagonist outrightly condemning fascist ideology. What makes this picture truly stand-out though, is the level of humour, with more gags and therefore laughs to be had than just about any production from the Great Man.

Porco Rosso comes ever so close to being top-ranked; but, as with Kiki, the conclusion arrives rather abruptly, almost to the point of being anti-climactic and leaving the viewer underwhelmed. Thankfully, no such issue plagues the next two entries on the list.

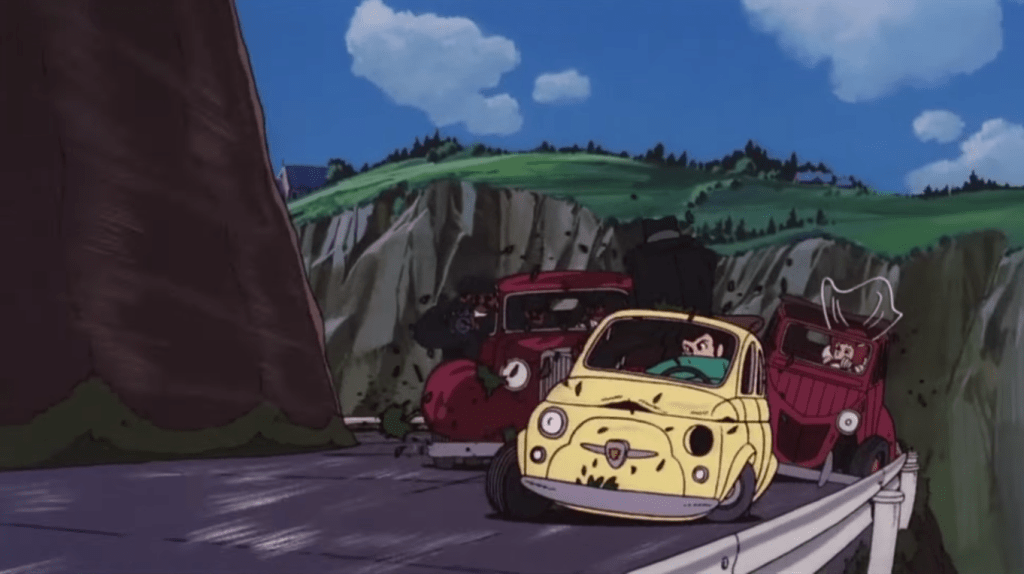

2. The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)

Miyazaki’s debut feature is one far removed from anything else in his filmography, yet proves one of his most entertaining works. Spinning off from the Lupin the Third TV series — which itself was based on the manga of the same name — Cagliostro tells of a gentleman thief who uncovers a counterfeiting operation in a dilapidated European kingdom, while simultaneously pining for the affections of the country’s Princess.

Laced within this ostensible crime-caper is a mystery bountiful in action and humour, as evidenced by a chaotic, destructive chase scene between a yellow Fiat 500 and two much-larger sedans (see above); our hero, Arsene Lupin III running full-pelt down the steepest of roofs; and Lupin desperately trying to escape a plunge of certain death by swimming up a waterfall! Additionally, there’s a surprisingly warm romance between Princess Clarisse and Lupin; and while the illustrations aren’t up to the standards of later Miyazaki efforts, they still have appeal.

Cagliostro was a critical and commercial success upon release in Japan, and went on to have a profound impact on several Western film-makers — its influence can be seen everywhere, from the climactic clocktower sequence in Basil the Great Mouse Detective (1986) to the Roman car chase in Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One (2023). Steven Spielberg is also said to be an admirer, with the story purportedly inspiring him to create Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

1. Spirited Away (2001)

Is it a cliché to consider this Miyazaki’s best film? At this point in history, possibly; yet to consider anything other than Spirited Away as his greatest achievement would be sacrilege. Inspired by Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland stories, it centres on a girl named Chihiro and her journey through a mystical realm of spirits, witches and beasts; a realm where she must grow-up in order to find her way home.

Along the way, viewers are met with imaginatively designed creatures; strangers who are curt and kind; stunning painted landscapes; and Joe Hisaishi’s gentle, catchy piano refrain that enters the ear like a cool breeze on a summer’s day. In terms of faults, the pacing is lethargic on initial viewing, taking a long time to establish the setting and its characters; and the screenplay is a bit too eager to portray Chihiro as a spoilt brat in its early stages, rather than a flawed heroine. But so haunting, moving and transfixing is the story that these qualms are more or less forgotten by its end.

Universally, rightly lauded, Spirited Away is to date the only Japanese production and the only hand-drawn work to have won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature; it’s also beloved by the public, sitting in the upper-echelons of the IMDb Top 250, and Letterboxd’s Top 250 Narrative Features. And, on a personal note, it happens to be the very film that fostered this writer’s interest in anime — there are almost certainly others who can say the same.

This is a film not to be ignored; a must-see for fans of animation, cinephiles, and indeed anybody with even the barest of interest in movies.