For horror season, the Criterion Channel has crafted an eclectic and bountiful collection of iconic Japanese Horror films to immerse yourself in. From ’60s cult classics to the ’90s and early ’00s staples that exploded the country’s unique horror classics onto the world stage, this collection has something for both the cinephile horror fan and those looking for an entry point.

The genre is defined by old folklore and urban legends about Oni, invisible demons that potentially bring disaster and disease with them. A key form of Oni is Yūrei, or vengeful spirits, which we can see spread across almost all Japanese horror cinema. Perhaps the most well-known story of Yūrei is of Okiku, a young maid who was thrown down a well by a samurai after she refused his advances, returning as a vengeful spirit. Okiku is defined by her long black hair and hushed whisper, iconography burned into the celluloid of the country’s horror storytelling for generations, forming the immortal image that spreads across this entire collection.

Japanese horror storytelling thrives when these legends of Yūrei and other Oni are weaved into their contemporary settings, from post-civil war anxiety (Onibaba) to suburban anxiety and community suspicions (Creepy) and the encroaching dominance of technology in our world (Ring, Pulse, Tetsuo: The Iron Man). This creates a consistent cultural imprint that makes the genre so satisfying to engage with and return to.

So what better way to spend October than to binge through these and craft a ranking list from this well-curated list of classics from the fine folks at Criterion.

13. Ichi the Killer (2001) – Takashi Miike

Extremist hyperviolence for the incels, industry legend Takashi Miike’s bizarre and underbaked screed Ichi the Killer, made two years after his brilliant film Audition (which will arrive later in this list), was banned in multiple countries for its approach to sexual violence and sadomasochism. Centring on the titular Ichi (Nao Ômori), an emotionally disturbed man who is just as likely to weep uncontrollably in the corner of a room as he is to violently murder those around him, most likely with a blade hidden in his boot. Pursuing Ichi is a sadomasochistic yakuza enforcer Kakihara (Tadanobu Asano), known for his brutality and Joker-like scars along his cheeks, who is impressed and tantalised by Ichi’s level of violence.

If that reads like a teenage boy fantasia of hyper-violence and extremity at the expense of taste and storytelling, that’s because it is. The only skippable film on this list, Ichi the Killer sees the chaotic filmmaker indulge in all his worst impulses which were weaved in more creatively in his other films.

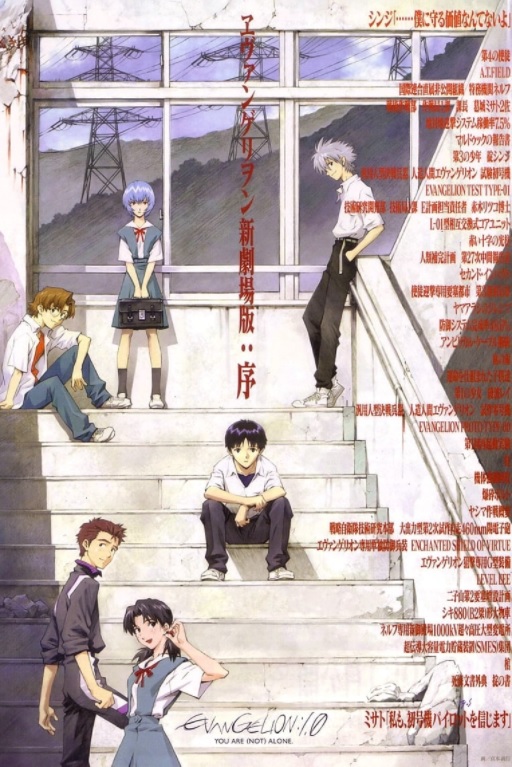

While the film and the manga it is faithfully adapting has clearly influenced a generation of filmmakers, particularly in manga and anime circles, its haphazard approach to storytelling centred on a hyper-violent incel creates an instant callous so thick, the proceeding depravity sparks little to no emotion.

12. Ju-On: The Grudge 2 (2003) – Takashi Shimizu

Even as the lesser of the films in the franchise selected by Criterion, Ju-On: The Grudge 2 is not without its iconic moments that each film in the franchise achieves. Operating in a surprisingly quieter, more atmospheric horror register, Ju-On: The Grudge 2 centres its plot on a TV crew working on a reality show about ghosts set in the house of the original film.

The Yūrei at the heart of the franchise stems from a murdered housewife, cursing all those who enter the house to an inevitable demise. The horror set pieces in the film and the franchise grow repetitive in a hurry, but still manage a psychological stickiness through some impressive genre flourishes. The ghost’s death rattle sound remains one of the great noises in the horror canon that ratchets up tension faster than any convoluted plot.

Following the similar trajectory of the previous film with its nonlinear narratives inside character (read, next victim) focused chapters, Ju-On: The Grudge 2 has a more menacing air of inevitability that never feels oppressive. Instead, it makes for an easier watch than the first film, albeit with the same issues.

The time-skipping narrative in this film is more potent and evocatively tied to the whole story than the original, making its climactic final act wash over you in waves of sadness and melancholy, even with its bizarre final ten minutes.

11. Ju-On: The Grudge (2002) – Takashi Shimizu

The all-time ‘just leave the house’ franchise, Ju-On: The Grudge thrives in the unknown. The horror is a tightly contained, well-chosen horror house, a small collection of characters and a looming presence we are desperate to learn more about, even if the resolution ultimately lessens the experience in the film’s uneven conclusion.

Ju-On: The Grudge’s keen focus on sound design with its wall scratching, cat screeches, and the iconic death rattle heightens an unfocused plot, held together by its terrific horror set pieces, Hitomi’s (Misaki Itô) chapter especially. Japanese horror, and especially those centred on yūrei have these unexpected and often moving notes of sadness at the heart of the curse, something that can be felt even within the iconic stair scene at the climax of the film, largely through Takako Fuji’s performance as the ghost Kayako.

Ju-On thrives in its limitations as a micro-budget film shot in a tremendous house for a horror, which Shimizu puts great attention to laying out, but is bogged down by a serious lack of characterisation, opting instead for time skipping and short chapters that prevent the inventive filmmaking to thrive. Ultimately, these films have such aggressively passive characters stuck in these doom loops that while tepidly compelling, never excel as an overall experience.

10. Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) – Shinya Tsukamoto

Pure heavy metal cinema that some have deemed ‘migraine cinema’, the wildly feverish Tetsuo The Iron Man leaves a crater in the medium we can only hope to mine for future resources. With the self-awareness to hit the ejector seat after 67 minutes, Shinya Tsukamoto’s manic sci-fi nightmare about a self-professed ‘metal fetishist’ (Tomorô Taguchi) is driven mad (or already was), creating a sequence of events which include a graphic and hysterical sex scene, an incredibly tactile chase sequence, all culminating in a transcendent moment of mania you’ll be coming down for days after.

This Japanese Eraserhead (1977) crushes your skull with a relentless pace and style, truly fitting its design aesthetic of violent machinery bursting from limbs like the chest burster in Alien (1979). There is no Crash (1996) or Titane (2021) (and to a certain extent The Substance, 2024) without Tetsuo, placing it violently at the top of the heap of the cinema of extremity, even if its ideas arrive with a blunted edge.

9. Dark Water (2002) – Hideo Nakata

A tense and poignant drama of a family going through a divorce wrapped up in a ghost story, Dark Water is a melancholic look at childhood neglect and trauma with a beautiful and unexpected third act.

Directed by Hideo Nakata who thrust the Japanese horror genre onto the world stage with Ring (1998) —appearing later in this list— based on a short story collection by Koji Suzuki (who also wrote the Ring novels), Dark Water centres on a young mother in the process of divorcing her husband and rebuilding a life for herself and her young daughter Ikuko (Rio Kanno). The mother, Yoshimi (Hitomi Kuroki), rents a rundown apartment for her and her daughter where strange occurrences happen, localising around the water in the building.

Four years after his enormous success with Ring, Nakata is driven to a more potent emotional story of childhood neglect and a fracturing family, lowering the temperature of the horror, using the genre instead to heighten the dramatic storytelling rather than as a means to an end. The film succeeds as a sombre piece of atmospheric storytelling that weaves two unique stories together, the family divorce drama that gives remarkable attention to the young child’s feelings throughout, and the ghost story in the apartment.

Held together by a pair of fantastic performances by Kuroki and Kanno, with the latter giving an all-time child performance in a horror film, Dark Water sneaks up on you with its deceptively poignant storytelling and characters, culminating in the most emotionally resonant final act on this list. The horror genre, and especially ghost stories, excel in articulating a sense of longing and lost time, with those we love and those that need to be loved.

8. Creepy (2016) – Kiyoshi Kurosawa

It is no mistake that Kiyoshi Kurosawa finds himself on this list three times, as the great master formalist makes a case for the most important voice in horror storytelling since John Carpenter. A film that understands the anxiety an audience gets from a whisper in a stressful situation, or a quiet interview in a frame full of people, Creepy brings Kurosawa’s doom scenario milieu to the suburbs, tracking an ex-detective Koichi Takakura (Hidetoshi Nishijima) forced to retire from the force and move with his young wife Yasuko (Yūko Takeuchi).

With a clear itching to return to detective work, as well as a heightened sense of danger and menace behind every door, influenced by a level of unresolved PTSD, Koichi becomes obsessed with a local cold case brought on by an ex-colleague, as well as being unnerved and suspicious of his neighbours.

Kurosawa’s formalism is well suited to the obsessive detective narrative, with the modern suburbia setting slowly pierced by the auteur’s signature sense of overwhelming dread and suspicion. His measured camera movements, at times unsettlingly ahead of the action, heighten the anxiety of any given moment, binding us to the experiences of his characters.

The legendary auteur is at his best when he can place the audience, alongside his characters, in situations where anything is possible. Like reality, not every moment is cause and effect, where potentially horrifying incidents can occur seemingly without motive or reason. This troubling, anxiety-fuelled sensation is where Kurosawa is more keenly tapped into than perhaps any living filmmaker, allowing his seemingly mundane character dramas to glide into some of the greatest horror moments of the past 30 years.

A bold perspective gearshift in the film’s second half almost derails the drama and tension Kurosawa so brilliantly establishes for over an hour, held together only by the filmmaker’s ability to reignite the dramatic flame for a memorable closing moment. While not in the highest tier of works, Kurosawa’s Creepy is as satisfying an unsettling portrait of suburban anxiety and destabilisation as you will find.

7. Ring (1998) – Hideo Nakata

The quintessential Japanese horror film, Hideo Nakata’s Ring is probably the most iconic film on the list, defined by its Yūrei antagonist Sadako (Rie Ino’o), clearly based on the Okiku legend, down to her horrific murder of being thrown down a well. It’s also the film that sparked a Western fever over the Japanese horror industry, rapidly adapting them into American versions of middling success (four films on this list have American adaptations), the best of the lot being Gore Verbinski’s impressive adaptation The Ring in 2002.

To catch those up to speed with the story of this blockbuster from Japan, Hideo Nakata’s Ring has the all-time horror premise of a mysterious VHS tape that, once watched, will have you scared into an early grave seven days after watching. Wonderfully blending Japanese folklore with modern society’s relationship with physical media and storytelling, all wrapped up in a moody yet propulsive journalism procedural centred on the brilliant Nanako Matsushima and Hiroyuki Sanada as ex-wife and husband pair Reiko and Ryūji.

Where Ju-On falters by being solely driven by its formula and inventive kills, Ringu thrives in its deep fascination with the looming spectre of Sadako, using the framework of the journalism procedural to uncover the reality that she is less a hostile ghost and more of an enraged victim.

The film elevates itself with an emotionally overwhelming moment in the climax, with Reiko warmly embracing the skeleton of Sadako, a graceful note in a film that until this moment thrived in its procedural meticulous storytelling. In a genre defined by outcasts reaping revenge on the world, this moment of tenderness pierces through the shroud of menace and cynicism, leaving behind a desperate mother letting her tormentor know it will be okay. Even though this moment is followed by a scene with the franchise’s most iconic imagery of Sadako crawling out of the television, it’s without question the film would be stronger for ending at this place (the TV crawl scene could happen at any point), perhaps moving it higher up this list.

6. House (1977) – Hideo Nakata

A destabilising horror experience, unlike anything you’ve seen before. With a feverish energy and imagination that removes an audience’s ability to anticipate an inch in front of their face —a crucial component of any great horror— Nobuhiko Ôbayashi’s House, playfully referred to as a psychedelic comedy horror, is the most unique film on this list that quickly became a global cult object.

A tremendously enjoyable film, House follows seven schoolgirls with names like Gorgeous (Kimiko Ikegami) and Kung Fu (Miki Jinbo, MVP of the group once the mania starts), played by mostly amateur actors, who go on a summer vacation to a country estate owned by Gorgeous’ aunt (Yōko Minamida), an eccentric older woman. Strange occurrences and violent episodes begin to plague the girls at the house, shifting the film from a glossily bizarre romp into a clear ur-text for Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead films while never losing its internal style and spirit.

Ôbayashi has made a film on such a different frequency to the rest of cinema, a feat that forces you to realign your senses to get onto its wavelength. But once you’re there, the results will astonish you. You’ll be so overwhelmed with a sense of dysphoria, oscillating rapidly between genuine glee and anxiety with its feverish editing style and use of stop motion and simple animations. In a secluded cabin where anything is possible, even a cat can become a nightmare.

5. Onibaba (1964) – Kaneto Shindō

The demonic nature of war and conflict which sows its violence into the very earth, Kaneto Shindô’s atmospheric and captivating 14th-century folk tale has perhaps the loosest attachment to the horror genre as anything on this list, earning its place through its deep connection to post-war anxiety, reflected through the prism of Japanese samurai cinema.

With her son, Kichi, away at war as a samurai, a woman (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law (Jitsuko Yoshimura) struggle to survive on their own in the outskirts of Kyoto, resorting to killing solitary samurai and stealing their swords and clothes to a local merchant for food. Upon the return of a neighbour, Hatchi (Kei Satô), who tells them of the death of the son, the trio begin a dance of seduction and connection fuelled by loneliness, jealousy, and desire.

Onibaba lives in the sound of nature in conflict with human violence, the aggressive rustling of grain and reeds, the coarse splashing of water on a riverbed as two nameless men fight, tying notions of human violence and horror to the very earth, better than almost any film has since. As the oldest film on this list, it is as crucial a watch as any in understanding the genre as a whole.

4. Kuroneko (1968) – Kaneto Shindō

Such a wonderful companion to his previous film Onibaba it’s impossible to separate the pair, with its casting of Nobuko Otowa in near identical roles, mirrored visual motifs and narrative of the women left behind and left to rot in the burnt ruins of a world left by feeble men.

Opening with the brutal murder of a woman, Shige (Kiwako Taichi), and her mother-in-law Yone (Otowa), at the hand of a band of samurai that sets the tone for the rest of this haunted revenge thriller as the pair return to the world as cat formed Onryō, a more vengeful form of yūrei.

In many ways, this is the more overtly horrific film of the pair, but where Kuroneko really excels and where Shindō clearly improves as a writer is in the dramatic storytelling that is unlocked in the centre of the film with the return of Gintoki (Nakamura Kichiemon II), Yone’s son, Shige’s husband, and crucially, a samurai. This return creates a compelling internal battle for Shige and Yone, who have returned to the mortal world to seek vengeance on the samurai plaguing and overwhelming the land, but still harbour a great love and longing for the man who left them.

At its core, Kuroneko is a story of vengeance against the inhumanity of male violence, with its beautiful knots of human longing and connection in the face of great pain piercing the heart more powerfully than any fang.

3. Audition (2001) – Takashi Miike

Recently ranked the 7th best horror film of all time by Variety, Takashi Miike’s second and much more successful entry on this list, Audition, moves as an anglerfish, enrapturing you in its romantic light, masking the dark monster lurking in the shadows.

Beginning with a beautiful three-minute prologue of a young family losing their mother in a hospital, Miike’s Audition blooms from a place of empathy and loss, creating a lush bed to destabilise us. Set seven years after this, Shigeharu’s (Ryo Ishibashi) son Shigehiko (Tetsu Sawaki) presses him to find a wife. Shigeharu’s friend Yasuhisa (Jun Kunimura), a film producer, devises a plan to hold an audition for a fake film project with the goal of Shigeharu choosing a wife out of the cohort.

Immediately, Shigeharu is enchanted, bordering on obsessed with one prospect, the quiet Asami (Eihi Shiina), and pursues her, even though Yasuhisa urges him to reconsider as he believes something is off about her. Miike uses his chaotic approach to editing and story structure that tipped over Ichi the Killer here as a piercing needle into the skin of this Vaseline-covered pulpy romance. It is in this needling contrast that the film thrives.

Miike has a profound eye for composition and lighting, transcending the material into a consistent wave of tangible emotion, never letting its characters or the audience off the hook he so delicately dangles. This lush style is wrapped in a discordant editing style once we meet Asami, reshaping any notion of the type of film we are watching from moment to moment, culminating in a wild final act that made the film legendary to horror fans.

2. Pulse (2001) – Kiyoshi Kurosawa

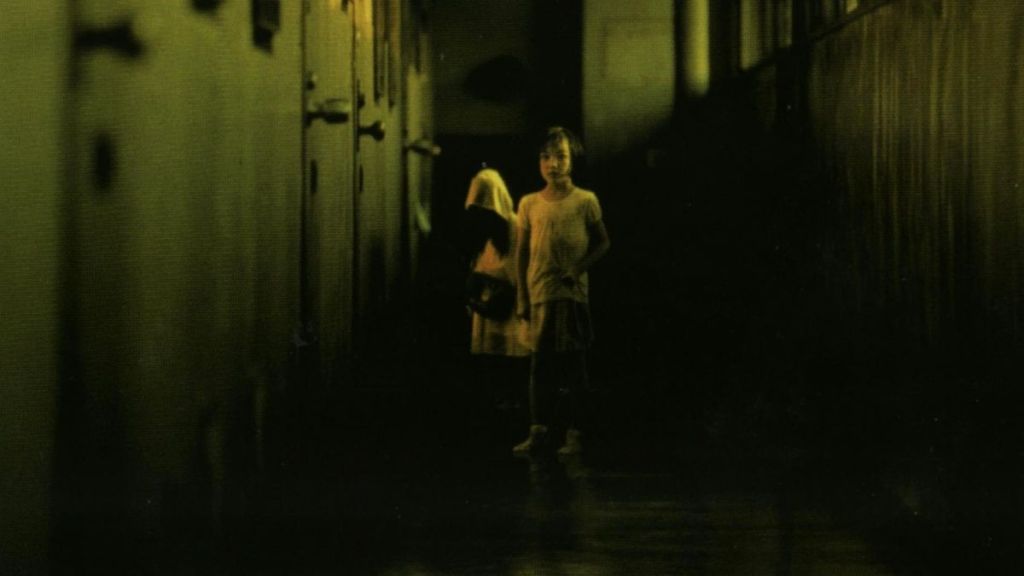

The year is 2001 and the legend Kiyoshi Kurosawa is deeply sceptical about the internet’s promise to connect the global population more deeply with each other. In Pulse, at the turn of the millennium with the internet burgeoning into being, a creeping loneliness epidemic appears to be bleeding into people’s lives through their computer screens, leaving its victims in a fate worse than death.

In conversation with Hideo Nakata’s Ring with their relationships to media and technology’s place as the medium to our new folk stories, Pulse elicits a similar feeling the VHS tape has with its steadily increasing number of apparent ghosts taking form inside the internet, desperate to escape for reasons that become clearer at the film’s remarkably evocative climax.

Viewing the relationship between a rapidly isolating city and life through the lens of a small group of young people retreating into their own worlds via the internet is eminently recognisable in 2024. With a steady march towards depression tied to the oblivion of disconnection that Kurosawa achieves better than almost any living filmmaker, we are forced into the role of both protagonist and camera operator, refracting our modern life into this 23-year-old film. For this reason, alongside its depressive but uncynical atmosphere, Pulse is potentially the definitive work of cinema for our online, modern age.

The miracle of Kurosawa’s films is their ability to form a compellingly bleak drama without an overwhelmingly cynical worldview. While the film is defined by suicide and internet-driven malaise, Pulse is never driven by a contempt for the ghostly presences or the young victims like in the Ju On films. Even in the final, apocalyptic moments, the audience, with Kurosawa by our side, is hopeful for a potential step forward.

With all that said, what supercharges these ideas and propels them into a plane few films achieve is their ability to operate as a truly terrifying work of horror. Even in a horror collection that boasts iconic horror scenes like the ones in Ring or Ju-On, nothing is as bone-chilling and skin-crawling as the slow-moving ghost sequence, perfectly calibrated to destabilise our ideas of how our fears can be provoked in such a simple scene.

The unveiling of the Big Bang event at the film’s core as a deeply personal, isolating act of exposed self-annihilation is overwhelmingly emotional. The best horror films root themselves in empathetic moments of anguish that birth a larger malice to those in its orbit, which Pulse achieves better than anything on this list and in almost any other film in the genre.

1. Cure (1997) – Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Perhaps the film I’ve thought about the most since watching it on a gloomy night in 2020, sliding ever higher up my all-time list, making its ultimate landing spot at the top here felt inevitable but still celebratory. Kurosawa’s best film, Cure, is the perfect blend of his obsessions of ingrained human anxiety and potential for violence, with his filmmaking influences, equal parts Andrei Tarkovsky and Tobe Hooper, flourishing at every turn.

Centring on obsessive detective Takabe (a colossal performance by Kōji Yakusho), with a deteriorating home life due to his wife’s (Anna Nakagawa) failing mental health, who is tasked with solving a series of seemingly random murders connected only by the assailants having carved an ‘X’ into the neck or chest of the victim. We are shown these violent attacks in Kurosawa’s familiar smooth camera movements, creating an unnerving balance that stems from the potential violence of everyday life.

Much like David Fincher’s Se7en (1995), a film deeply tied to Cure, our burgeoning obsession with true crime storytelling is being reflected back at us, forcing us to contend with our own impulses towards viewing violence in this way. Cure excels because Kurosawa is keenly aware of these impulses and genre conventions, understanding when to subvert them or allow them to play out at his own deliberate pace.

Cure’s greatest act of subversion comes from the crafting of perhaps the best horror character of the past 30 years, the black hole known as Mamiya, the man seemingly hypnotising people into performing these murders. Portrayed with a compelling aloofness by Masato Hagiwara that disarms both the audience and other characters, while also flooding the air with a palpable sense of tension and dread. Mamiya’s hypnotism scenes are extraordinary set pieces in magnetic genre filmmaking, focusing on elemental connections like the flame of a lighter or the meditative quality of washing over you like a steadily rising tide. The film transcends past its terrific villain and set-pieces due to our near-instant tethering to Takabe’s obsession with understanding these murders, propelling us deeper and deeper into the world and ultimately, Mamiya’s spell.

Takabe’s ultimate decision to give his ailing wife over to an asylum creates an absence inside him that allows him to reach the precipice of defeating Mamiya but directly asks us the cost of this sacrifice. In a world void of something to fight for, how does one look into the abyss and see anything but themselves? In a genre of scares and nightmarish atmospheres, these lasting questions and closing moments will have you questioning how you view humanity itself.