With another year having drawn to a close, Rating Frames is looking back at the best new releases of the last twelve months.

It was a difficult year for the medium, owing to numerous delays and cancellations – these retrospectives would be quite different had MIFF been able to run its full schedule – but there were still some excellent films released that we all wanted to celebrate.

In the last of our end-of-year articles, Arnel Duracak will be revealing his ten favourite pictures of 2021.

In arguably one of cinema’s most challenging years ever, 2021 surprisingly stood the test of time to become one of the best years for films and film lovers in the 21st century.

There were films by Paul Thomas Anderson, Steven Spielberg, Wes Anderson, Denis Villeneuve, Todd Haynes, Edgar Wright, Jane Campion, David Lowery, Lana Wachowski, Steven Soderbergh, M. Night Shyamalan, Shaka King, Zack Snyder, Sean Baker, Mike Mills, James Gunn, Lin Manuel Miranda, Adam McKay, and Ridley Scott (two from him) all coming last year, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

My point is, as impacted as cinema was in 2021, there was a silver lining in terms of the films we got from the large pool of iconic filmmakers available. My list is a sum of my experiences with some of those filmmakers and their films, and here’s to a promising 2022.

10. The Last Duel

Having one new Ridley Scott film these days feels like a rarity that needs to be savoured, but two? Now that’s like seeing a UFO. But The Last Duel isn’t just rare because it’s a film from a legendary filmmaker in his later years, it’s also a film that doesn’t come around too often. In fact, this film is Ridley Scott at his directing best, all the while bringing in the grit and tension that make his films so enjoyable.

Through a chapter like structure, this film is about the closest thing we have to Scott’s iconic Gladiator (2000) as it keeps you engaged right throughout courtesy of some clever editing and writing, and it sees Jodie Comer deliver her best performance yet (even outshining her male counterparts Adam Driver, Matt Damon, and Ben Affleck to a lesser extent given his minimal on-screen time).

The Last Duel is also memorable due to its practical filmmaking (incorporating practical combat rather than taking the easy route through CGI), well worked story, and captivating performances. Unfortunately, Scott’s other film of 2021, The House of Gucci, doesn’t hit the same high as this one but both are worth watching if not for want, then for the icon that is Ridley Scott.

Currently streaming on Disney+.

9. Nobody

I can only imagine that screenwriter Derek Kolstad’s logline to get this screenplay green-lit was “John Wick but with Bob Odenkirk dialled up to 11”. Nobody is the John Wick (2014) of 2021 and this was one of the first films I saw in a packed cinema at the start of 2021. It was an exhilarating experience and one that got me excited to get back into the cinema.

With a relatively simple premise that sends Odenkirk on a revenge killing spree after his daughter’s Hello Kitty bracelet is nabbed during a failed house robbery, Ilya Naishuller’s Nobody is a joy ride from start to finish. While the film doesn’t capture the awe and suddenness that came with seeing a rampant Keanu Reeves in John Wick back in 2014, Nobody is still a rowdy 90 minutes at the cinema.

The closing sequence is one of my most memorable from last year with a shotgun wielding Christopher Llyod going berserk alongside Odenkirk — Doc and Saul Goodman really paint the town red here.

Currently streaming on Prime and Binge.

8. The Mitchells vs. The Machines

When adding films to my top of the year list, I kept asking myself “why does this film deserve a spot on my list?”; in the case of The Mitchells vs. The Machines the answer was pretty simple: there wasn’t an animation like it in 2021.

Michael Rianda does a stellar job with telling a story about family and the drama of family life, while also managing to tap into ever present fears around technology as it becomes more advanced. This animated road movie is essentially We’re The Millers (2013) meets I, Robot (2004) but it’s actually funny and it actually handles its subject matter quite well.

The animation style here has been spoken about a bit, and while it does take a bit of time to adjust to the striking style like with Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018), the animators prove that animation doesn’t need to be a cookie cutter process.

Currently streaming on Netflix and available on DVD.

7. Minari

The second of my two 2020 films seen in 2021 courtesy of Australia’s awful theatrical schedule, Minari is a compelling piece of storytelling by Lee Isaac Chung that focuses on themes of family, loss, the American dream (or whatever that means today), and the immigrant experience.

With a cast that gives it their all (comprised of Steven Yeun, Han Ye-ri, and Youn Yuh-jung whose performance won her an Oscar), a well written script, and excellent direction, Minari has a bit of everything for everyone.

Coming from an immigrant background with refugee parents, this film really hit home in terms of the difficulties families experience when moving to a new country and the struggles of growing up relatively poor. If you haven’t seen Minari yet, what are you waiting for!

Currently available on home-video and on-demand services.

6. The Father

The Father is a heartfelt and considerate film that provides a unique outlook on the struggles of dealing with dementia from the perspective of a character dealing with the condition.

Director Florian Zeller directs his play of the same name and he’s evidently had the look of this film down pat for a while — focusing on enclosed spaces with lots of mid-shots, close-ups and extreme close-ups and using space to his advantage.

With Anthony Hopkins winning his second Best Actor Oscar and making history as the oldest actor to win a Best Actor Oscar at the ripe age of 83, this film is all about the performance. It’s an interesting idea to look at the condition from the perspective of the patient, and Zeller does so by brilliantly playing with time through smart editing and staging (take note Nolan).

While this film is technically listed as a 2020 release (as is another on this list), Australia unfortunately has an awful theatrical window so I’ve had to adjust accordingly and this film deserves a place on my list.

Currently streaming on Prime Video and Foxtel Now.

5. Dune

Having read Frank Herbert’s novel of the same name shortly before its release, Denis Villeneuve’s Dune is blockbuster filmmaking at its very best that honours Herbert’s writing through visual splendour that only the cinema can offer.

The film has everything you want from a blockbuster: scale, mesmerising world-building, a lived in feel, a large ensemble, wondrous set pieces, a resounding score, and (for the most part) grounded storytelling.

Villenueve has once again proven his worth by tackling a piece of fiction and an iconic title often deemed unfilmable due to its scope and depth, and he’s left his imprint on it in the process. He incorporates his fondness for slow cinema with plenty of moments of recollection and contemplation to be had, and he sets the stage for a sequel that will no doubt have a lot more riding on it given the success of this picture (especially considering his 2017 feature, Blade Runner 2049 was a box office flop).

The film is not flawless given that characters aren’t all that interesting and the performances are quite mute (there’s not one that stands out from the other), but it’s a fitting first adaptation of half of Herbert’s novel and lays the foundation for a (hopefully) more spectacular part two.

Currently screening in theatres nationwide and will soon be on Blu-Ray.

4. C’mon C’mon

A film that was unbeknown to me for the majority of last year, C’mon C’mon is one of those cozy and warm films that you would just want to hug if it was a tangible object.

Mike Mills writes and directs this tender story of connection and self-discovery, with two resounding performances from the incomparable Joaquin Phoenix and newcomer Woody Norman. Phoenix plays Johnny, the uncle of Norman’s character Jesse, and the two of them spend the film together after Jesse’s mother leaves town for a week or so to tend to her mentally ill husband. What ensues is a sweet and earnest film that revolves around a shared journey of self growth as the two characters confide in one another and open each others eyes to the world around them.

The film is shot in black and white which works to its advantage as, even among the very colourlessness of the world, the two characters stand out like a sore thumb; in other words, by being in each others company and experiencing the world through unfiltered conversations (particularly from Jesse), these two become the most colourful parts of the world. Mills meticulously builds his story through the characters’ shared experience to the point where their bond and relationship leads Johnny to view the world in a different light and have a much needed awakening or wake up call.

Children and their world view is at the forefront of the film as Johnny interviews various child subjects due to his radio profession, but Jesse is his gateway to something more real, and Mills makes sure that reality is felt beyond the diegetic world.

Releasing in select Australian cinemas on the 17th of February 2022.

3. In The Heights

In what felt like the year of the musical with West Side Story, Tick Tick Boom, Dear Evan Hansen, and Annette, it was In The Heights that reigned supreme in 2021. I’m usually not a big fan of the musical genre — with The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) being an exception — but In The Heights rekindled my faith in the genre and in its future in cinema.

Jon M. Chu directs the hell out of this adaptation of Lin Manuel Miranda’s first successful broadway musical, which is filled with brilliant choreography and item numbers, a dedicated cast, an infectious energy that sucks you in the longer the film plays out, and a considerate, thought provoking perspective on gentrification and the Latino community at its core.

I must say, I’m yet to see West Side Story, but In The Heights was really the film to get me excited for everything else that would grace our screens in 2021, and it came at the right time during the despondent events that continue to plague the world.

Currently available for rent on Prime and for purchase on DVD.

2. Pig

Michael Sarnoski’s Pig moved me in ways that no other film in 2021 had. With a simple yet gripping story and an emotionally charged Nicolas Cage cashing in his best performance in years, this film hit all the right emotional chords for me — leading me to rewatch it a few days after my initial viewing.

Pig doesn’t go down the conventional route of a revenge thriller even though it might appear that that’s the direction Sarnoski is heading; instead, the film is about reflection, mourning and a wider commentary on how we forgo what we love in favour of a life of conformity in a capitalist system where we ultimately lose sight of who and what we are.

There are so many layers in Pig for a runtime of around 90 minutes, and had Licorice Pizza not been released, this would have been at the tippity top of my list.

Currently available on home-video and on-demand services.

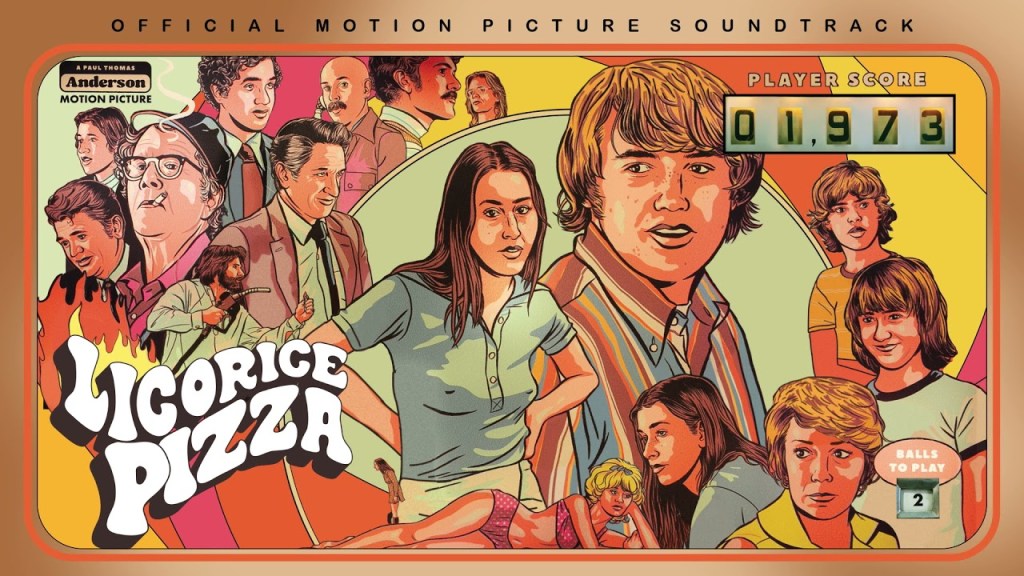

1. Licorice Pizza

That brings me to Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest, or the quintessential film of 2021. It takes everything we know and love about PTA — his undying connection to the San Fernando Valley, the 70s period, characters that are larger than life, the themes that underpin his work, the formal devices from his cinematic toolkit — and meshes it all into one. The result is a heartwarming tale of self-discovery and companionship, and one that traverses the fine line of adolescence and adulthood while managing to bridge the two worlds together.

Acting newcomers Cooper Hoffman (Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s son) and Alana Haim (from the pop rock band Haim), deliver captivating and confident performances of youth angst and free spiritedness. Their chemistry is magical and infectious and it’s hard not to see bits of yourself in their performances (such is the magic of PTA’s screenplays).

Licorice Pizza was always going to be a shoehorn for one of my favourite films of 2021 due to the man at its helm, but it deserves all the praise it has received and it deserves to be seen on the biggest screen you can find.

Currently screening in select theatres nationwide.

Honourable Mentions: Encanto, Annette, Judas and the Black Messiah, The Matrix Resurrections