Given their ubiquity, changes in cast and wildly varying degrees of quality, casual moviegoers could be forgiven for thinking that the James Bond films are always produced by a different studio, their rights exchanging hands more frequently than Bond himself changes lovers. In actual fact, these rights have stayed with the same two companies for decades, both holding the exclusive licence to adapt Ian Fleming’s stories and characters to celluloid.

Well, almost.

In the six decades since producers Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli were granted Fleming’s permission to turn his novels into feature-length pictures, there have been 27 films released with Agent 007 as the lead character. 25 of those movies – including the upcoming No Time to Die (2021) – have been made by Eon Productions, a company founded by Broccoli with the sole purpose of creating Bond films; the remaining two have not.

The production and release of these movies was, on both occasions, made possible due to legal loopholes that allowed individuals to circumvent Eon’s authority and craft their own adaptations of Fleming’s works. Neither picture is remarkable, but nonetheless, both are important pieces of cinematic history that contribute to Bond’s legacy, and as of such are worthy of discussion here on Rating Frames.

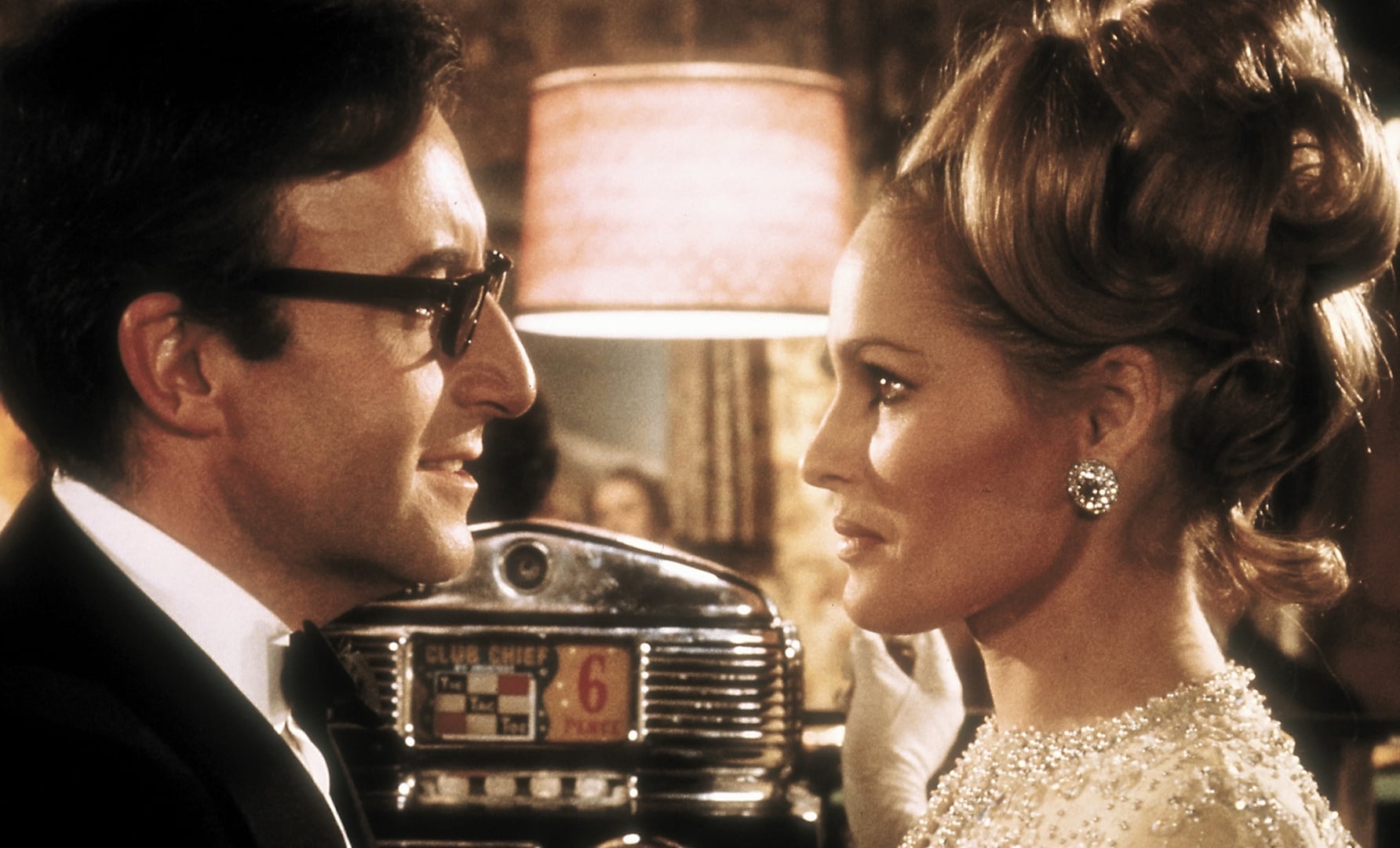

The first of these two films is Casino Royale (1967) which arrived at the height of James Bond’s popularity and mere weeks before Eon’s You Only Live Twice (also 1967) hit theatres. Its title is shared with Fleming’s debut novel, and not by coincidence – the rights to this book were optioned by American producer Charles K. Feldman, who unsuccessfully tried to adapt the story with Saltzman and Broccoli. When his relationship with the pair fell through, Feldman decided to continue on with the project alone, eventually securing the backing of Columbia Pictures.

Feldman’s Casino Royale is a picture that deviates wildly from its source material, being a slapstick parody that centres on an older James Bond (David Niven) coming out of retirement to mitigate a crisis at the behest of his former superior. The picture benefitted from a celebrity-laden cast that included not just Niven, but also the likes of John Huston, Peter Sellers, Orson Welles (yes, really!) and original “Bond girl” Ursula Andress, in addition to future stars Woody Allen, Jacqueline Bisset, Ronnie Corbett, Bernard Cribbons and John Bluthal.

Why actors of such calibre wanted to be involved is a mystery, because Casino Royale is an unmitigated mess of a movie, with the pacing being too fast, the screenplay lacking coherence, and the comedy being atrociously unfunny, with just about every gag falling flat. Its only redeeming feature is an irreverent finale that appears to have inspired Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles (1974), but even this moment of absurdity proves just as underwhelming as any other scene in the picture.

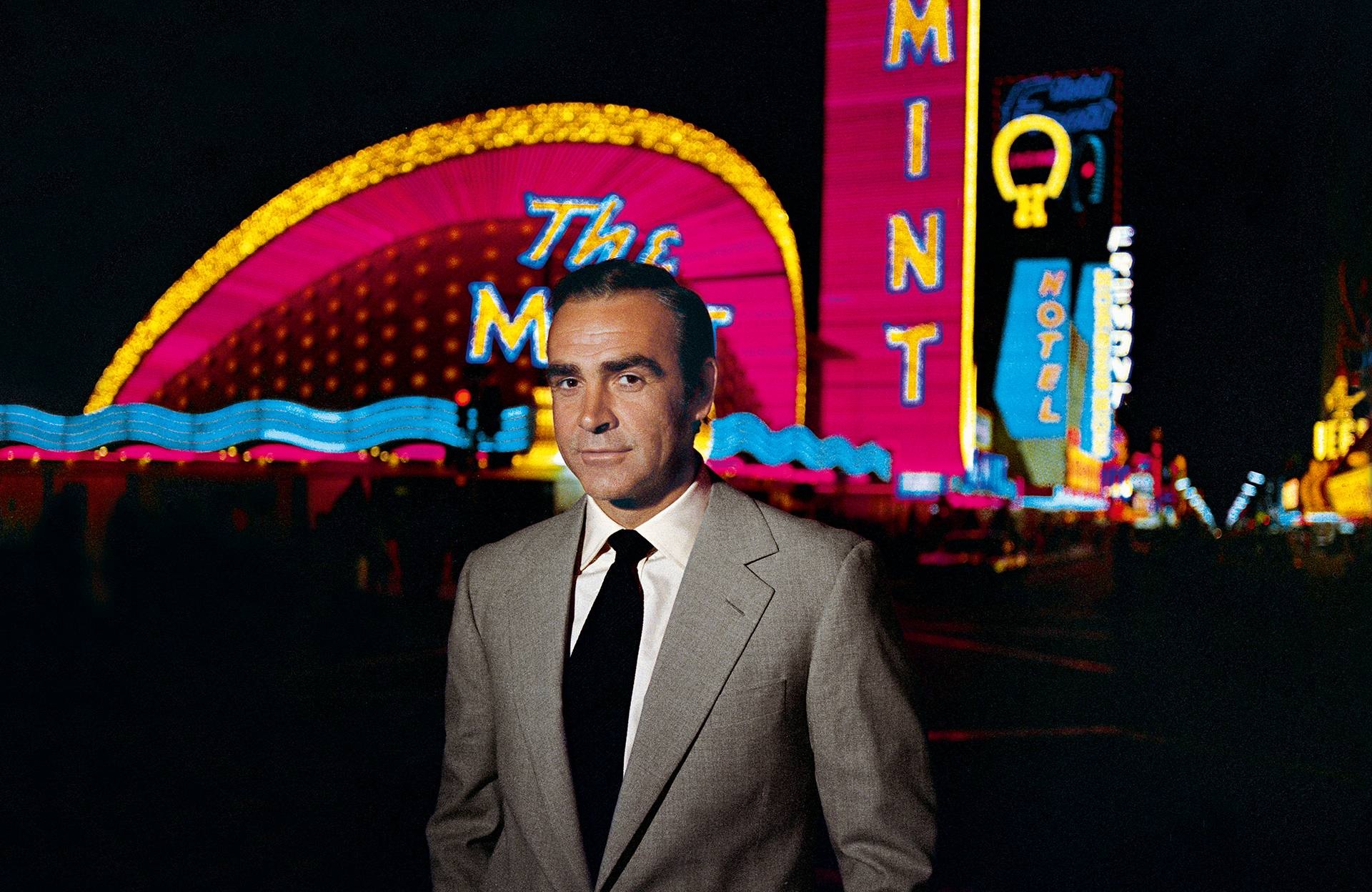

By comparison, the second of these “unofficial” Bond films is a masterpiece, if only because it possesses a level of competence non-existent in Feldman’s production. The film in question is Never Say Never Again (1983), which owes its existence to screenwriter Kevin McClory. Prior to Saltzman and Broccoli’s acquisition of the film rights, McClory was approached by Fleming to adapt one or more of his books, but instead chose to write an original story with Fleming’s input – a story that was novelised by Fleming and published under the title of Thunderball in 1961.

A legal battle between McClory and Fleming ensued, one that went to court and saw McClory awarded damages plus joint authorship of the novel. With this small credit, McClory also had control of the rights to Thunderball, thus gifting him with the power to make his own picture if he saw fit. Those rights were eventually sold to film producer Jack Schwartzman; but since there was already a movie called Thunderball (1966), significant changes were needed to differentiate between the two – most obviously the title.

Never Say Never Again is a virtual rehash of Thunderball’s screenplay, with the fresh cast, updated visuals and the like doing little to disguise this fact; moreover, the newer adaptation is less fun than the Eon production, for it lacks the Sixties aesthetics and fantastic music that make the original picture such a charmer. Yet because it lacks camp and takes itself rather seriously, the film manages to be better than the “official” Bond title released that very same year, Octopussy (1983). Though only just.

In short, both of these movies pale in comparison to their Eon counterparts – one fails as both a compelling spy movie and an astute satire of the source material; the other is serviceable, yet unable to offer anything new or unique. If this author were to place them in our countdown of the other 25 Bond films, Casino Royale would be dead last, while Never Say Never Again would fall between Moonraker (1979) and Licence to Kill (1989), neither of which are 007’s finest hour.

If there’s one positive that can be said about the two unofficial films, it’s that they provide the viewer with a greater appreciation of the Eon-produced pictures, demonstrating the value of Saltzman and Broccoli’s input and why their movies have endured, instead of becoming relics from a bygone era. Or how not to do a Bond flick.