Long before superhero franchises came to proliferate theatres, there was just one man guaranteed to be a box-office drawcard: Bond. James Bond. His handsome looks, sophisticated wardrobe and suave tongue have allured filmgoers for decades, despite his notoriety as a heavy-drinker and misogynist, with his popularity enduring to this day. And next week, he’ll be returning to the limelight once more when his newest picture, No Time to Die (2021), finally debuts in Australian cinemas.

For the benefit of the uninitiated, Bond – who is also referred to by his codename, 007 (pronounced “double-oh-seven”) – is a spy who works as part of the British government’s secret intelligence service, nowadays referred to as MI6. His character originated in a series of wildly-popular novels penned by Ian Fleming and published at the height of Cold War-paranoia, before making his first big-screen appearance in the 1962 adaptation of Dr. No.

More movies starring the secret agent would follow in the years after, with the premise, tone, style and cast occasionally adjusted to suit the tastes of audiences, with varying degrees of success. Like many others, the team at Rating Frames has been revisiting these pictures, and can now offer to you their definitive ranking of the James Bond film franchise, listed below from worst to best.

24. Live and Let Die (1973)

Roger Moore’s debut as 007 is by far and away the most embarrassing entry in the character’s history, filled with painfully unfunny one-liners, far-fetched stunts and plenty more illogical moments. A decent boat chase on the Louisiana Bayou is the only element that saves it from being unwatchable.

23. The World is Not Enough (1999)

“Monotonous” is the word that best describes this Pierce Brosnan-led bore, doing nothing to innovate the genre, nor the franchise. It’s long, slow, bland, and made even more frustrating by the presence of Denise Richards, the most unnatural and ineffectual “Bond Girl” to ever grace the screen.

22. Quantum of Solace (2008)

A misguided affair that takes a few too many cues from the Bourne movies and not enough from its predecessor, which also starred Daniel Craig. The pacing is too fast, camerawork too shaky, narrative lightweight, and Mathieu Amalric’s villain feeble at best.

21. Octopussy (1983)

This one is the most light-hearted of all the films, bordering on parody – especially during the third act; yet it’s not without its charms, with some good chase sequences, decent fights and tension involving a nuclear bomb. Certainly not a stinker, but nor is it Moore’s finest hour.

20. Licence to Kill (1989)

007 goes rogue in Timothy Dalton’s second and last picture as the secret agent, and things get very dark in the process. Quite simply, it’s too violent, too graphic and too angry for a Bond flick, its tone better suited to a Scarface knockoff.

19. Moonraker (1979)

This romp saw Bond fly into outer-space in an effort to capitalise on the science-fiction craze of the late Seventies, resulting in the silliest, campiest film of Moore’s tenure – and that’s really saying something, given the quality of his other movies. With that said, the space sequences are reasonably entertaining.

18. The Man with the Golden Gun (1974)

A pretty tepid and rather forgettable affair for Moore, with the exception of its two antagonists: Sir Christopher Lee as the main foe, Francisco Scaramanga, and Hervé Villechaize as his short-statured associate, Nick Nack. That corkscrew jump is pretty cool, too.

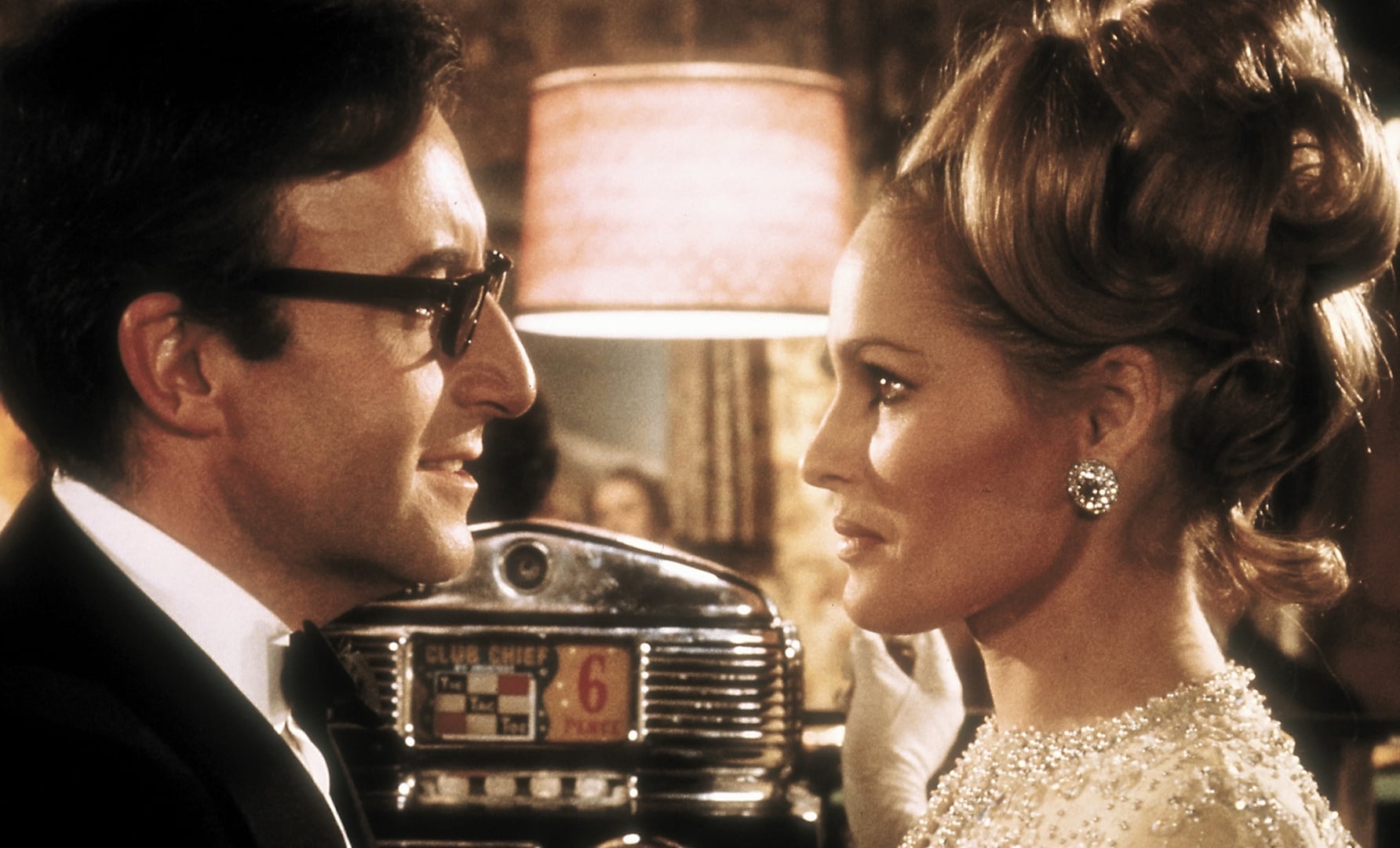

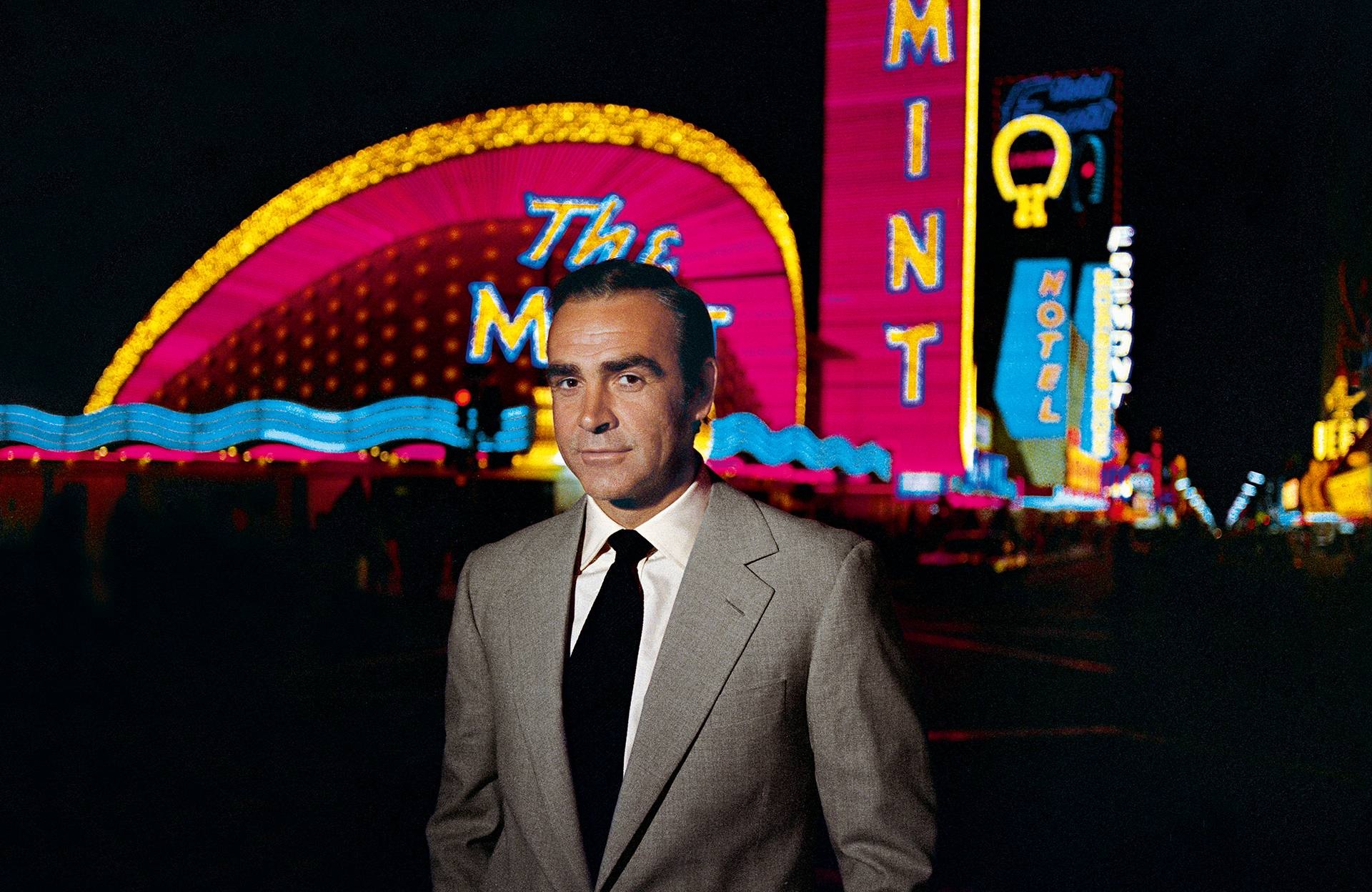

17. Diamonds Are Forever (1971)

The last official Bond film to star Sean Connery, who is virtually the only aspect that elevates proceedings. This instalment marked the franchise’s transition into camp, with bright colours and many ludicrous moments, yet is simultaneously dullened by its flat, lifeless Las Vegas setting.

16. Die Another Day (2002)

Often derided as the worst in the series, but nowhere near as bad as its reputation suggests, Brosnan’s final appearance as 007 contains a bonkers, yet fun, car chase on ice with military weaponry, and a tense climactic battle aboard a jumbo jet. Just be sure to suspend all disbelief.

15. The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

Introduced a great adversary in Jaws (Richard Kiel), and an iconic ride in Bond’s white Lotus Esprit that doubles as a submarine; beyond that though, Moore’s third movie as lead is pretty mundane, and in need of some greater thrills.

14. A View to Kill (1985)

While Moore was definitely too old to be leading an action flick by this point, his swansong is good nonetheless, boasting two of the series’ best villains – Max Zorin (Christopher Walken) and May Day (Grace Jones) – and the occasional moment of high tension.

13. You Only Live Twice (1967)

Cultural appropriation of the Japanese aside, Connery’s fifth outing stands the test of time, with all the Bond trademarks present. Plus, there’s a memorable climax inside a secret lair that sees Bond’s first face-to-face encounter with his arch-nemesis: Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Donald Pleasence).

12. Dr. No (1962)

The first ever Bond film is by no means spectacular by today’s standards, yet remains one of the better instalments due to its straightforward narrative – one that’s reasonably faithful to Fleming’s original novel – and serviceable thrills. A splendid introduction to the secret agent, even if some of the effects look cheap.

11. Thunderball (1966)

Another much-loved entry from the Connery era, this one is marked by its extended underwater sequences that look exceptional; less so the editing, particularly in the third act. Probably has the driest sense of humour of any Bond script, too.

10. Tomorrow Never Dies (1997)

There’s lots to appreciate in Brosnan’s sophomore excursion as 007, including a genuinely terrifying first act, a delectable antagonist, and the presence of Michelle Yeoh, who brings with her some exciting close-quarters combat. But the pacing is too quick, and there’s a few too many corny punchlines.

9. The Living Daylights (1987)

In the first of his two appearances in the franchise, Dalton steers proceedings in a more serious direction than his precursor did, to great effect. The chase scenes and stunt-work are exemplary; the narrative involving a group of Afghan freedom fighters hasn’t aged very well, though.

8. For Your Eyes Only (1981)

The best, and least camp, picture from the Moore era, made enjoyable by the action sequences, a pretty decent twist involving the villain, and an understated sweetness that’s missing from most other instalments; yet it remains quite silly when compared to its contemporaries.

7. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969)

One of the more distinctive entries in the Bond canon, owing to the snowy backdrops, romantic subplot, and George Lazenby in his first and only turn as 007. The icy driving scenes and ski chases are especially pleasing, even when paired with some unconvincing effects.

6. Spectre (2015)

Often lambasted for being too slow and too predictable, and both criticisms are valid; but the qualities of this movie cannot be denied. Caters to the franchise’s purists with its brutal fights, chase sequences and aircraft wreckages.

5. Goldfinger (1964)

Considered the quintessential Bond flick, and with good reason. Boasts two iconic villains in Auric Goldfinger (Gert Frobe) and Oddjob (Harold Sakata), in addition to a gadget-laden Aston Martin which has come to be synonymous with the series and the spy genre as a whole. Tacky effects and substandard editing let it down.

4. Casino Royale (2006)

Loosely inspired by Fleming’s debut novel, this is the chapter that rebooted the venerable series and introduced Craig as a cold, unflinching 007. It’s gritty, taut and occasionally brutal, factors that don’t always work to the material’s advantage; nor, for that matter, does the embarrassing product placement.

3. From Russia with Love (1963)

An improvement over the previous year’s Dr. No in practically every respect, courtesy of a higher budget that allowed for more action and stunts. Justly remains the feature by which all other Bond films are judged.

2. Skyfall (2012)

Deftly combines the tropes of its forebears with an intimate, grounded screenplay to create a product that pleases Bond aficionados and casual viewers alike. Quite simply, it’s one of the best blockbusters ever produced.

1. GoldenEye (1995)

Here is the genesis for the modern James Bond film, an early and brilliant demonstration of how to balance tradition with evolution, the serious with the silly. Pierce Brosnan, sublime and effortlessly comfortable in the lead role, is faced with a pair of equally formidable antagonists who can predict his every move, and the conflict that ensues is nothing short of thrilling. GoldenEye is the franchise’s finest hour, and a must-see for everybody.