It’s that time of year again when people across the world start getting their pumpkins ready for carving and their costumes ready for wearing. It’s also that time of year when horror fanatics dive into their favourite horror films as Halloween nears. To prepare you for Halloween on the 31st of October, I thought I’d make a list of 9 campy, schlock-horror films to watch before the 31st. Most of these films are about as B movie as you can get with their small budgets, practical effects, zany plots, and comical performances. So lets look at some of the titles.

Bad Taste (1987)

As a life-long devotee to anything Peter Jackson related (given I’m a Kiwi), Bad Taste is about as great a debut feature as one can make. Not only was this film made with a small budget, but it was able to do so much with how little it had. Jackson made this with his friends and shot most of the film at his parents NZ house, with a documentary somewhere online showing his mum handing out sandwiches in-between takes.

The film has some structure for about the first 15-20min and then just quickly goes off the rails as practical effects subsume all coherency, and all out carnage ensues. There’s a scene involving barf drinking, there’s blood squirting almost consistently, there’s dudes in ninja costumes, guns galore, and there’s RPG explosions.

The film is really a testament to Jackson’s creativity and it’s far from his best schlock induced work (Braindead would follow), but it is a thrilling and outright enjoyable 90 minutes that never gives you any respite. It’s crazy to think studio executives would give Jackson The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003) to direct, but boy did they make the right choice.

The Evil Dead (1981)

It’s hard to make a list like this without including Sam Raimi’s ever celebrated The Evil Dead. In its 40 years, the film has withstood the test of time to become a cult classic in the horror genre. The film, while definitely more of a professional, serious production, would go on to inspire and pave the way for a wave of 80’s and 90’s schlock horror and campy films.

The premise revolves around a bunch of college students, a cabin in the woods, and a mysterious book that unleashes a demonic force to hunt the students down. It really is a premise with three signature horror elements that has been parodied and done-over countless times.

It’s another example of making do with what you’ve got, and boy does Raimi make do. Plenty of gore to be had and also scares, which is something that this film has over the others on the list as it is more of a nuanced horror that happens to fall into this schlock category as well.

Frankenhooker (1990)

Frankenhooker is just as its name suggests — a Frankenstein zombie made from the body parts of prostitutes. Made by Frank Henenlotter, known for such titles as Basket Case (1982) and Brain Damage (1988), Frankenhooker is about a guy that blows up some prostitutes and stitches them back together to create his dead fiancé (who was killed by a lawnmower).

The film is a comical exploitation film that leans into physical humour for laughs. Though the film falls under sexploitation and is no doubt misogynistic, it has retained a cult status for its nonsensicalness and bemusing premise. The film gets more wild as the scenes roll on, with Elizabeth (the concoction of those prostitute parts) eventually getting a greater consciousness and exacting revenge.

There is evidently a lot of love and care that has gone into the film which give it that rewatch status and it’s no doubt a trashy 90 or so minutes to be had.

Braindead (1992)

If I haven’t made it obvious, I’m a sucker for anything Peter Jackson related. Braindead is no exception and is one of the best films in the schlock horror, B movie category.

New Zealand humour and LOTS of blood subsume the film in this gore fest where Jackson is pretty much set on just destroying any and all human costumes and props. From the outset, Jackson is set on entertaining the audience as he leans into chaotic scenes involving intestine like creatures, zombies, swinging babies, and all while injecting the film with delirious gags and infectious humour.

Braindead is to the comedy-horror genre what Blade Runner (1982) is to the sci-fi genre.

Night Train to Terror (1985)

I don’t know where to start with this film. It’s like if Snowpiercer (2013) met Zoolander (2001) and Step-Up (2006), and even then that would still be an understatement. The film is quintessential viewing if B movie, schlock horror comedies are your thing.

Everything takes place on a train and the stories are absurd with multiple different ones intertwined throughout. The acting is bonkers, the humour feels out of place but works because it is, the practical effects are a staple of the time, and for some reason God and Satan are just having a casual chat amidst all the chaos.

It’s really an experience to be had rather than one that can be articulated as, like Sean Baker says on Letterboxd, the film is “Such an insane mess of a movie”.

Killer Klowns From Outer Space (1988)

As its name suggests, the film is about some killer clowns from space that come to earth and terrorise those they meet.

There really isn’t much to say in the way of what to expect or what works. Everything works because it doesn’t — the absurdness of the plot and performances lean into a humorous telling, and there is just a bunch of nonsensical killing that many would find is “so bad it’s good”.

I’m usually not good with horror movies in general let alone horror movies with clowns, but because this film (like most on this list) are as crude and bizarre as horror movies go, it was worth a mention.

Chopping Mall (1986)

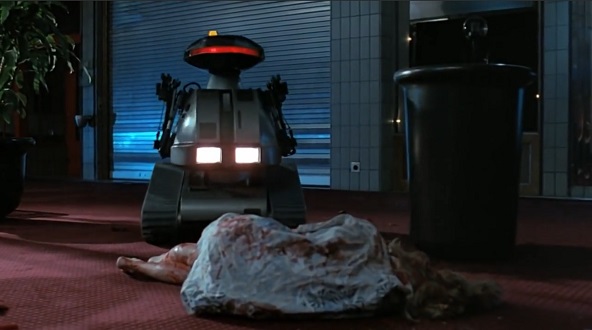

Aside from having one of the greatest simple titles of any film on this list, Chopping Mall is also (from memory) the only film on here (save for Death Spa) that brings robots into the equation!

I like to think of this film as The Breakfast Club (1985) meets WALL-E (2008), only WALL-E is a killer robot. Teens basically get trapped in a shopping mall after the mall goes into lockdown, only for security robots to go on a killing spree to rid these ‘intruders’. That’s really it.

The film is about as 80’s B movie as they come, with lots of satirical elements (particularly pertaining to mall culture and how prominent that was among teens at the time), scenes involving electrocution and also laser death.

Death Spa (1989)

Like Chopping Mall but also unlike Chopping Mall, Death Spa sees the spa computer system turn the workout equipment and other facets of the spa (including steam rooms and hair driers) against the spa goers.

It’s a ludicrous film (but what film on this list isn’t?), with garbage acting and a forgettable premise, but it keeps people coming back for its absurdity and how it doesn’t hesitate to knuckle down on its trashiness. The props and practical effects are lacking in comparison to most of the films on this list, but it has that 80’s vibe and colour palette that seem to be enough to keep viewers coming back.

The only thing missing from the film is Arnold Schwarzenegger and this would have been the Mr Olympia training film of the century.

TerrorVision (1986)

Rounding off the list is a film where a family’s newly installed satellite dish attracts alien signals and eventually, the aliens themselves.

The film is a bizarre delight with cheap set designs, a very satirical undertone (basically ripping into everything 80’s), goofy characters, a surprisingly diverse cast (including Gerrit Graham, Jon Gries, and Bert Remsen), a very cartoony feel, and practical effects that get the job done.

Essentially, if you wanted to get an idea of what the 80’s looked and felt like (from the hairdo’s, fashion, music and comedy), then this is the film for you.