With 2023 drawing to a close, Rating Frames is looking back at the past twelve months of cinema and streaming releases that have come our way. In the first of our series of articles, Darcy Read is taking a look at his ten favourite films of the year that was.

2023 has been a bizarre but ultimately wonderful year in cinema. A film year that felt like a genuine rebound after multiple years of roadblocks — and that’s with long-running SAG and WGA strikes with impacts felt in the latter stages of the year but will impact next year more on the ledger — through the success of ‘Barbenheimer’ and the return of some of the best veteran filmmakers we have working. While none of these storied filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, Hayao Miyazaki, or Wes Anderson delivered a film that will be the first project referenced in their obituary, all have produced work that will contend for the best cinema has to offer this decade.

As 2023 draws to a close, it is clear this year has the potential to enter legend status alongside calendar years like 1999 or 2019, with its combination of peaks and depth by creators both established and emerging, gifting us deeply personal works that have clearly resonated with audiences around the world. 2023 has been a wonderful year to write about for the site, and 2024 looks to be a fascinating year with the return of incredible artists like Bong Joon-ho, Steve McQueen, and Barry Jenkins to name a few. But before we get ahead of ourselves, here is my list of the best of cinema this year.

10. Oppenheimer

A vicious knife fight to land on the 10th spot on this list with a collection of wonderful films by veteran auteurs like Hirokazu Kore-eda and David Fincher, but the scale and power of the fleeting moments in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) proved too difficult to ignore. Nolan has been on a manic kick in recent years, adopting a sound-focused filmmaking pursuit that is just catnip for me. Combining an all-time score by Ludwig Göransson with an elastic soundscape that never lacks emotional or narrative potency by the legendary Richard King, Nolan and emerging editor Jennifer Lame throw you into the subjective war zone that is J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The film is littered with flaws and strange moments that threaten to derail the three-hour tirade through the scientific pursuit of unprecedented destruction, but the rigorous nature of the film allows for some transcendent sequences that stack up amongst Nolan’s very best work.

9. The Eight Mountains

A serene indie film shot across stunning vistas of the Italian Alps centred on two men building a house in a plot of land owned by one of their recently deceased fathers, Felix van Groeningen and Charlotte Vandermeersch’s The Eight Mountains (2022) plays out like a contemplative short story across two and a half hours, a personal favourite flavour that is not a universal palette.

The earnestness of the storytelling about two complicated men seeking purpose through their past and into their present transcends into a reflective pool of emotion and intimacy with a mesmerisingly natural performance by Alessandro Borghi as Bruno. Grab some tea and warm up by the fire of this enchanting Italian epic that would work as a perfect double feature with Past Lives (2023), a film we will get to.

8. May December

A sticky, chewy meal of a film, May December (2023) is less interested in the central scandal of the story (echoing the story of Mary Kay Letourneau and Vili Fualaau) than in the modern societal structures around a tabloid scandal, with the insidious media ecosystem that invades lives for an increasingly uncertain gain and the human impact that ripples out decades later, as the scandal itself.

Casting director turned screenwriter Samy Burch is perfectly matched on the screen by the brilliant Todd Haynes, a filmmaker most comfortable getting into the weeds of a dark, complicated story and emerging with something equally compelling and repugnant. The trio of performances from Julianne Moore, Natalie Portman, and the emergence of Charles Melton present this knotty and potently transgressive story with a heightened tension of melodrama whilst never losing the humanity at its core that allows the film to shine.

7. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

It took months for me to embrace the ‘to be continued’ nature of Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023), but once that hurdle is vaulted, the Jackson Pollock-styled explosion of creativity and narrative inventiveness on display in this sequel to the hit animated superhero film Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018) took hold.

Across the Spider-Verse’s first 20 minutes is the greatest example of riotous, shotgun blast openings to come across in years, miraculously blending art styles with raw emotion and vulnerability that created an avalanche of ideas to cascade from beginning to end.

6. Asteroid City

“Am I doing it right?” Anderson has long been known for his extensive production designs and air-tight dialogue, but what stands out in Asteroid City (2023) is the attention placed on the act of looking. These looks of longing and understanding permeate every moment and every character of the film. From June (Maya Hawke) and Montana’s (Rupert Friend) longing looks of romance tinged with the desire for understanding in an increasingly incomprehensible world, to the gazing scenes of Jason Schwartzman as both Augie in the play with Midge (Scarlett Johansson), and as the actor Jones Hall with the actress of his wife that was ultimately cut played by Margot Robbie – in one of the scenes of the year – Anderson reflects the modern world’s unease and uncertainty by displaying these feelings across the extended ensemble.

Schwartzman — who has never been better — wears layers upon layers of uncertainty about the future and how to feel in the present across his face, opening up like a flower in the final act. By penetrating the hermetically sealed world that Anderson and his crew craft here in Asteroid City with touchingly modern feelings of uncertainty and fear, the potency of the message burrows its way into the soul, where it has remained all year. “Am I doing it right?”

5. The Zone of Interest

The normalisation of genocide as a collection of active, domestic choices, Jonathan Glazer’s attentive formalism is a perfect match for this profound piece of art on the naturalism that real evil lives within. Based on a slither of Martin Ames’ book of the same name, The Zone of Interest centres on the young family of Höss, mass murderer and commandant of Auschwitz, as they live day to day alongside unimaginable horror. Glazer avoids almost all iconography of the camp and world inside of the walls, tightly focusing on the family mundanity through scenes of pool parties, teatime chats, and grandmothers coming over for a weekend as the black smoke billows constantly above them.

Glazer, alongside sonic collaborators Johnnie Burn and Mica Levi as sound designer and composer has crafted a piece of cinema that transcends the formal exercise it easily could’ve become, instead striving for an art film that lands close to a Nazi-based Jeanne Dielman (1975). There is no, and may never be, another experience like it.

4. La chimera

One of the great pleasures of following the career of an emerging artist is seeing them put it all together. In La chimera (2023), Italian filmmaker Alice Rohrwacher perfectly blends the rich, textured grounds of Tuscan farm life of The Wonders (2014) with the magical realism and whimsy from her revered film Happy as Lazzaro (2018) to create one of the year’s best and most creatively rich films.

Set in 1980s Tuscany, we follow Arthur (an extraordinary Josh O’Connor) and his band of tombaroli — Italian looters archaeological heritage — as he returns to his long lost love Beniamina’s local town after a stint in jail. Rohrwacher’s seemingly limitless filmmaking inventiveness wraps around a knotty and evocative story of local heritage and ownership of the past shot gloriously on 16 and 35mm.

3. (How Do You Live?) The Boy and the Heron

Went with the original title for this entrancing and engaging gift of cinema, as it so perfectly captures the film in many ways compared to a seemingly rushed decision to rename this endlessly compelling feature from another old master Hayao Miyazaki. Not only is the title How Do You Live? (2023) taken from a beloved Japanese novel that Miyazaki has called an ur-text for him creatively — heightened by having the book play a crucial story beat with it being gifted to our protagonist Mahito by his recently deceased mother — but it works as the central thesis question for the film Miyazaki came out of retirement to ask. A question he gives no answer to, understanding that a life’s purpose is in the pursuit. The film operates as a deep meditation on life and grief from a world-weary filmmaker and as a goofy, playful Ghibli movie with its eccentric parakeets and Warawara’s that are sure to make their way into the heart of the recently opened Ghibli park.

What allows these larger ideas and themes to flow freely across this entrancing film is the work of longtime collaborator Joe Hisaishi’s score, somehow in career-best form after all these years, echoing these thematic questions through his delicate strings, tense orchestrations, and loving piano melodies that wash over a crowded audience like an emotional wave. No film on this list has better potential to leapfrog up to number one than this film, probing for questions on day-to-day existence than any piece of art released in 2023, like only a true master storyteller can.

2. Past Lives

Saw this treasure of a film back in June at the Sydney Film Festival and remained top of this list for months, Past Lives (2023), the best debut feature of the year by Celine Song, has stayed top of mind for 6 months through its unique mixture of personal and romantic longing with a powerful trio of performances by Greta Lee, Teo Yoo, and John Magaro.

In Past Lives, the present is framed in a unique liminal space, an uncertain future result of past decisions and indecisions, more so than a real time experience, like watching Richard Linklater’s miraculous Before trilogy simultaneously across three screens. How Song is able to merge these ideas inside a tight 105-minute narrative feature is not to be understated, crafting the best screenplay of 2023 and one that will only expand and mature moving forward.

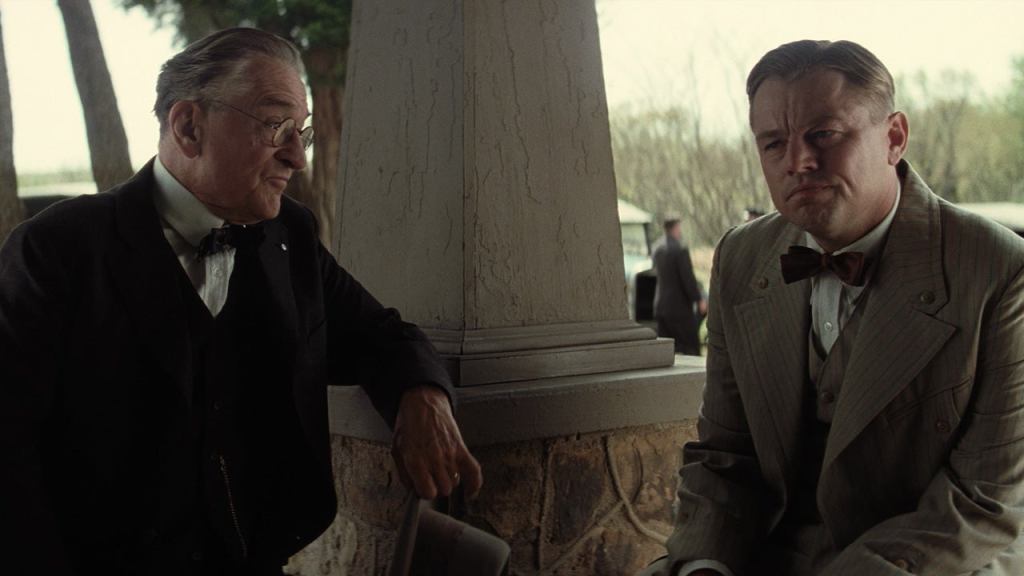

1. Killers of the Flower Moon

From my review for the film: “Killers of the Flower Moon (2023), a sprawling period crime epic based on the incredible best-selling nonfiction book of the same name by David Grann tracking the 1921 Osage Nation murders (potentially hundreds even though the reported count reached only 20), is the best film to arrive in theatres in years. An astonishing work, capturing the clashing worlds of empathy and cruelty, the legendary director Martin Scorsese alongside veteran screenwriter Eric Roth, set out to explore and probe the original sins of white exploitation and destruction that dismantled a once thriving community in the Osage Nation.

With a task as grave and serious about a community unfamiliar to their own, Scorsese and Roth’s script remarkably lands at a point of empathy and understanding they can reach as outsiders to this world. Scorsese’s self-reflective limitations as the person to tell this story are palpable throughout the film. This crime film’s capacity to tell a story of a community not his own arrives at a peak in a final sequence that may not evoke the same emotions in audience members as personal opinions of this vary. However, it is disingenuous to wholly dismiss this remarkable film on those grounds, just as it is disingenuous to wholly dismiss the air of white guilt and limitations as storytellers that frame Killers.”

My only five-star film of the year, Killers of the Flower Moon may not reach the Mount Rushmore of Scorsese’s career but is more than worthy of entering the discussion once the greatest living American director decides to hang it up.

Honourable Mentions: The Killer, Monster, How to Blow Up a Pipeline, Barbie, Showing Up.