Driven, work-oriented men who struggle to balance the personal with the professional and are often trapped by their own desires has always been Michael Mann’s bread and butter. In Ferrari (2023), his latest foray into biopics after Ali (2001), Public Enemies (2009) and to a lesser extent, The Insider (1999), he tackles automotive titan Enzo Ferrari. A figure notorious for his desire to win at all costs, Ferrari fits perfectly into the book of self-destructive but purposeful protagonists that Mann has been exploring.

A perfectionist professionally but a loose cannon personally, Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver) was a multi-faceted man, with his mind ever so focused on innovating and winning races but also ever so muddled when it came to his marriage and family life. Mann wastes no time in connecting those two worlds, introducing Ferrari (after a short montage of recreated black-and-white footage of a young Enzo behind the wheel) slipping out of the home of his mistress Lina (Shailene Woodley), slowly pushing a car downhill before jumping into it and speeding off. It’s a subtle introduction but helps establish what follows as a deeper look beneath the bonnet.

Where he’s speeding off to is his blindsided, somewhat estranged wife Laura (Penelope Cruz) whom he shares his struggling business with as well as a deceased son, Alfredo, whose death is a trigger point Mann continually comes back to over the course of the film to access that hidden internal layer that Enzo tries to hide.

It makes sense to ground the film to a particular moment in time rather than simply treating this as a by-the-books, cookie cutter biopic. The moment he chooses here is in 1957, with Enzo continuing to grapple with the loss of his son while living a double life with another woman and a second child, Piero. It’s a period in time where the Ferrari brand was at risk of collapse and the Mille Miglia race was a way for Enzo to clap back at doubters and hopefully, debt.

Mann is an expert at extrapolating key info from his subject matter, something Driver attests to in a Collider interview by stating that Mann’s characters “internal lives are so rich and so specific” and that “all of his notes are about character and internal life”. And Troy Kennedy Martin’s screenplay, based on Brock Yates’ Enzo Ferrari: The Man, the Cars, the Races, the Machine, offers enough legroom for Mann to build out the sort of bubbling tension that Enzo is harbouring over the course of the film where you feel that at any given moment, something will burst as it often does in his films.

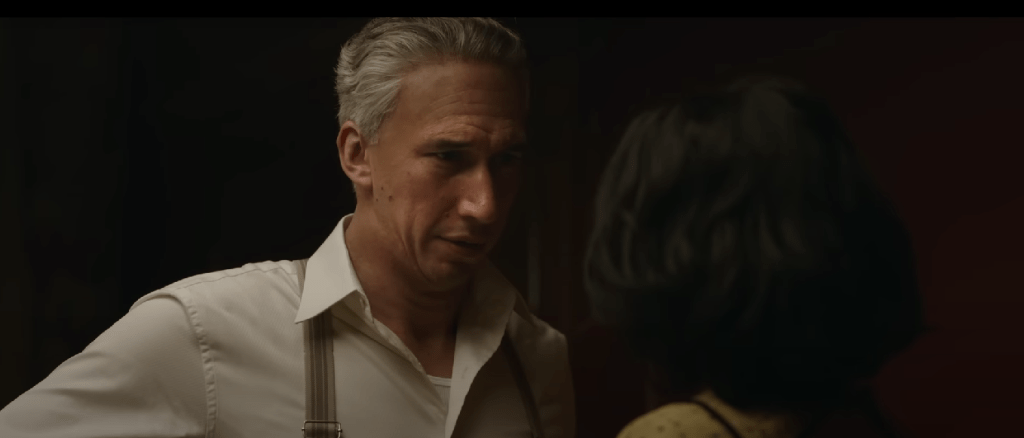

As mentioned, the Mille Miglia feels like the Hail Mary for Enzo to redeem his brand, and across the film he tests cars around a track with professional drivers while reminding them that it’s a privilege to race in one of his cars. It’s in these very transaction-like conversations that his ruthlessness and hunger to win comes through, with Driver playing the Commendatore (as he was known) with a composed edge but towering presence as though he was truly a force of nature in this world. Not to take away from Driver, but at times his performance feels a little less accessible than some of Mann’s other characters who share similar traits but often have a more engaging charisma.

It’s in the more personal exchanges he has with those he cares about that the true duality of his life comes through. Laura matches him in bluntness, with the loss of their son evidently creating a rift between the two that’s left them stagnant in their marriage. Cruz’s performance here is up there with the best of the year as she plays Laura as a woman on the cusp of losing it, with her dark, hollow eyes and blank expressions evoking the rawness she stills feels for her son’s death and distance from her husband.

While the film is more of a melodrama in its muted moments, it wouldn’t be a Mann film without some thrills and spills. The racing sequences, including that of the track tests and the Miglia itself, are shot expertly by cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt with cameras situated in seemingly every part of the car except the drivers laps. The sound-design adds to the flair of the races and the sense of foreboding doom as the cars rocket around turns and narrowly avoid knocking into each other.

The closing sequence is one of the most confronting of Mann’s career and definitely of the last year, with a crash that kills nine onlookers at the Miglia. Sure the CGI feels a bit jarring in a film that focuses on practical effects for its majority, but the moment itself and Enzo’s reaction afterwards speaks to the coolness that he projects where things happen in this line of work and you move on, because that’s what winners do, no matter the cost.

Ferrari is in theatres now.