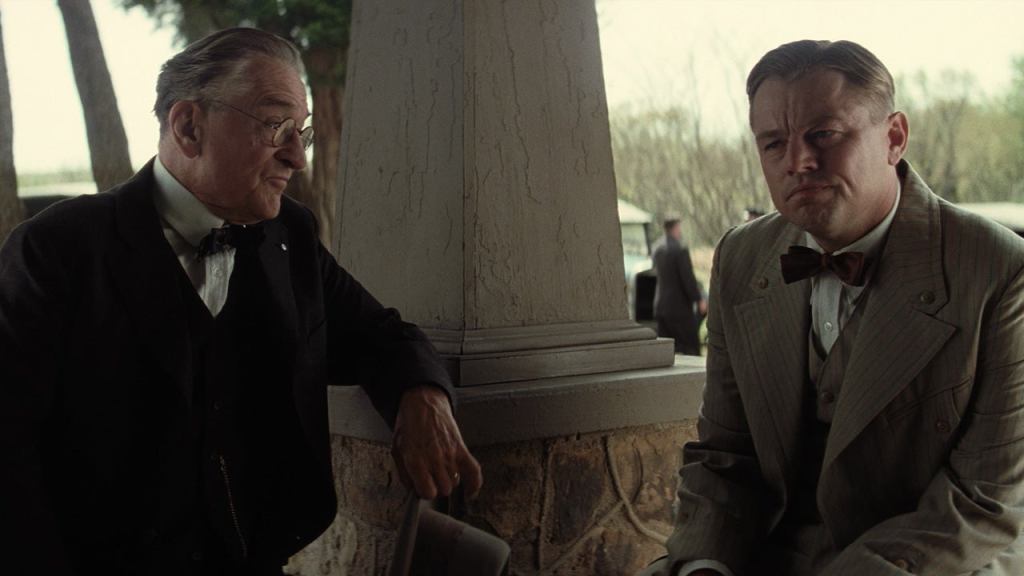

“Can you find the wolves in this picture?” As the simple Earnest (Leonardo DiCaprio) reads from a history book given to him by his uncle William “King” Hale (Robert De Niro) about the Osage Nation, to acclimatise himself to the new land in Oklahoma he has found himself in after returning from the war, we are not so subtly asked to investigate the frame of each scene. The land is almost entirely owned by the First Nations Osage community that, after being slaughtered and chased out of other states before finding themselves here, struck a reserve of oil on the land they had legal rights to, making them the richest per capita community in the world. And now their people are being brutally killed in careless succession, with the government nowhere in sight to investigate.

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023), a sprawling period crime epic based on the incredible best-selling nonfiction book of the same name by David Grann tracking the 1921 Osage Nation murders (potentially hundreds even though the reported count reached only 20), is the best film to arrive in theatres in years. An astonishing work of the clashing worlds of empathy and cruelty, the legendary director Martin Scorsese, alongside veteran screenwriter Eric Roth set out to explore and probe the original sins of white exploitation and destruction that dismantled a once thriving community in the Osage Nation.

Central to the story is Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone in the must-see performance of the year), and her family who were amongst the wealthiest in the community through their Osage headrights. From the opening moments of the film, the plan is established by the wolf Hale: set up his family to marry into and then assassinate Mollie’s family to gain their land through these headrights, with the newest entrant Earnest, Hale’s young (in reality Earnest was 19) nephew with nowhere else to go, to be placed alongside Mollie.

With a task as grave and serious about a community unfamiliar to their own, Scorsese and Roth’s script remarkably lands at a point of empathy and understanding they can reach as outsiders to this world. Scorsese’s self-reflective limitations as the person to tell this story are palpable throughout the film. This crime film’s capacity to tell a story of a community not his own arrives at a peak in a final sequence that may not evoke the same emotions in audience members as personal opinions of this vary (more on this later). However, it is disingenuous to wholly dismiss this remarkable film on those grounds, just as it is disingenuous to wholly dismiss the air of white guilt and limitations as storytellers that frame Killers.

The film is a surprisingly straightforward narrative story, using its 206-minute runtime to form as tight a compulsive story as is possible with Grann’s sprawling book, with the marriage of Earnest and Mollie at its core. There are many changes in structure and perspective to the book, with the most crucial being the shift in storytelling philosophy with the character of William Hale. In Grann’s book, the revelation of Hale’s orchestration of the gaining of head rights through systemic murders of the Osage Nation plays out closer to a whodunit true crime thrill ride that concludes with the formation of the FBI and the men that uncovered the truth — a sharp contrast to how the story is presented in the film. By changing the storytelling style from a whodunit into a bottomless well of foreboding dread through our connection to his character, Scorsese is tying us to the poison in his veins, feeling the bounds of the American condition and original sin within this vile man more directly.

Roth’s original screenplay focused on a more procedural whodunit that would’ve subbed as a perfectly adequate recreation of Grann’s book, centring early on Mollie and following onto Tom White’s (Jesse Plemons) role in the FBI investigation. Scorsese, in his first co-screenwriting credit since Silence (2016), alongside Roth, altered the perspective of the script, maintaining focus on Mollie and Ernest. In Grann’s book, the primary question being posed is: who is the culprit of these hideous acts? In Killers, the power of the storytelling comes from pursuing the more unanswerable questions at the core of their relationship and marriage: How can you do this to someone you believe to love? And how can you not see the root from which all these horrible events are stemming from? The boiling frustrations that stem from these probing, emotional questions are allowed to simmer across the entire extended runtime of the film, evolving into a profound sadness that will last with you a lifetime. Very few films attempt this level of emotional connection with the viewer, and even fewer films achieve it.

What allows Killers to capture an audience’s hearts and minds across its extended runtime is the trio of performances by DiCaprio, Gladstone, and De Niro in one of the finest ensembles in Scorsese’s storied career. De Niro, in his best performance in many years, is nightmarish as the wolf Hale, able to talk and smile through both sides of his mouth, taking up residence as a haunting figure of colonial greed and arrogance in the early 20th century. Alongside him is DiCaprio in his Calvin Candie mode from Django Unchained (2012), a performance style he has grown more comfortable with in recent years. The choice of DiCaprio to play an individual some 30 years his junior is a fascinating one. It can be read as a director pulling his muse into another film for the central role, or as a compelling provocation to the audience of seeing the star portray a despicable and complicated person. The weight of Earnest’s wilful ignorance is also deepened when placed across DiCaprio’s face than a more age accurate performer. What allows the film to transcend however, is Gladstone, perhaps the most compelling screen presence to emerge in a decade, whether in a single scene in the great TV series Reservation Dogs (2022) or Certain Women (2016), she is simply astonishing. Gladstone’s chemistry with DiCaprio is established early and becomes the crux of the film, with each scene together tethered to an anchor of tension that remains all the way into their incredible final meeting.

There are arguments to be made that Gladstone is sidelined for too much of the back end of the film due to her illness, which is as much a compliment to her performance as a narrative choice. This element of the film is also forced due to the reality of Mollie’s poisoning and illness, a storytelling hurdle that would’ve been disrespectful to sidestep. Her powerful presence is felt on and off screen equally, her piercing eyes hold a deep well of humanity which buries into your psyche for the elongated runtime. To avoid this aspect of the real story is to avoid the real pain that was subjugated on each member of this community, something that was clear throughout the production as being integral to telling this story. This family of women, with Mollie at the centre, want for a normal, wealthy American life that should have been afforded to them, but the ingrained systems of racial vilification and capitalism — the two are intrinsically linked — force them into a victimhood they should have been able to avoid through their wealth.

The longer Roth and Scorsese worked with the community, listening to their stories and hearing their truth, the deeper the well of understanding was established which is felt in powerful sequences throughout the film. A key moment displaying this respect to the Osage Nation is in the profoundly moving sequence as Lizzie (Tantoo Cardinal), Mollie’s mother, passes on, holding hands with her ancestors as she walks, smiling and without regret, into the next life. The sequence is quiet, simply staged, and made with great respect, with the air of an Apichatpong Weerasethakul film. The sequence echoes Silence (2016), Scorsese exploration into his own faith late in life, through its stripped-down and respectful style, displaying the utmost care when dealing with the faith of the people portrayed on screen.

By saddling the audience with Earnest for much of the film, a man with absolutely no moral core in the centre of the frame, Scorsese seeks to probe and destabilise us in equal measure. We don’t have the comforts of a future-set flashback to reassure us of his remorse, nor do we have saccharine familial moments that give us an easy out of the atrocities portrayed in the film. The further and further we are stretched, the more determined we are to uncover some hidden truth in DiCaprio’s performance, but he is equally as withholding with us as he is with his own wife. Over 200 minutes, the greatest living filmmaker is asking us not to find the wolves in sheep’s clothing, but to ask how these wolves can live amongst sheep after consuming their families.

As an Australian, it’s impossible to ignore the echoes of our own history in this story, of The Stolen Generations and the arrogant dark seed of colonialism at its core. The pain in seeing the universality of these vicious and callous crimes is overwhelming, especially as it overlaps with this year’s referendum vote. It has never been easier to be wilfully ignorant of our past, dooming ourselves to continue them.

This dark cloud hangs over many aspects of the story of Killers. There is a deliberate air of inevitability to the murders and distressing moments of the story, shown through the edit and deliberately bleak sound cues that saddens whilst never veering into an unbearably solemn experience. Too often a film, especially an epic of this scale and runtime, will lose all propulsion as a compelling narrative in order to express the grave nature of the experience. This is a balancing act that is beautifully achieved, where the wealth of film knowledge of Scorsese and his long-time crew shines through to create this tremendous work of art.

Legendary musician and collaborator Robbie Robertson in his final work feels an inch off screen at all times, holding court on proceedings through his Stratocaster with a beautifully anachronistic score that brings to mind the famous Neil Young improvised score for Dead Man (1996). The real highlight piece for Robertson is the mournful guitar and vocal duet “They Don’t Live Long”, which seeps into your bone marrow through its mixture of seething rage and sorrow at the feeling of utter helplessness to these vile acts we are bearing witness to.

There is a care taken to each death that is heart wrenching and overwhelming that builds across the film. These moments aren’t calloused, or moments of entertainment that Scorsese has been accused of leaning too heavily on in the past. They are stark and honest, allowing the pulverising emotion of an audience experiencing these brutishly evil acts without a guide rope.

There is a special kind of pain Scorsese is carving out of you through the ham-fisted manner in which these horrific crimes are taking place. Not only is no one properly investigating these crimes due to the collective apathy those in real power hold for the Osage, but that is understood by those involved. This is not some elaborate web of seemingly innocuous murders, but a collection of obvious crimes committed by a group that never thought they’d get caught due to the privilege they wield over this community. For the master of the organised crime genre in cinema to focus on this collection of brutish, disorganised crime figures is pointed and considered, a continuation of his previous film The Irishman (2019), which is present throughout.

The film concludes with a charming Lucky Strike-helmed 50s radio play — sponsored by the FBI, valorising and sensationalising their involvement in the events — performing the events that transpire post the film in place of the usual text over photographs that close many a nonfiction adaptation. In these final moments, Scorsese enters the frame in an emotionally charged note to Molly’s ending, emanating both a solemn goodbye and apology for the nightmarish life she had to endure. He is overtly surrendering to the material and the Osage Nation. Not in some Variety interview or for your consideration campaign spot, but in the very text itself. The greatest living American filmmaker – and perhaps the country’s greatest ever auteur – closing potentially his final film in this manner will resonate till the end of time.

Killers of the Flower Moon is in select theatres now and streaming soon on Apple TV+.