With 2024 having drawn to a close, Rating Frames is looking back at the past twelve months of cinema and streaming releases that have come our way. In the second of our series of articles, Darcy is taking a look at his ten favourite films of the year that was.

With a dense collection of titles with no clear standout, 2024 was the hardest year to rank recent releases in a long time. With a collection of new voices and revered personal icons, 2024 had a wide mixture of films that went head-on in tackling modern life, something that has felt lacking in the last few years. The only key omission to this list upon release is Ramell Ross’ Nickel Boys, a book I love from an exciting new artistic voice in the medium I’ve been desperate to see all year, which is releasing via Amazon at the end of the month. With that being said, I’m happy with how this list came together and hope these rankings get someone to check out a new exciting film.

10. Chime

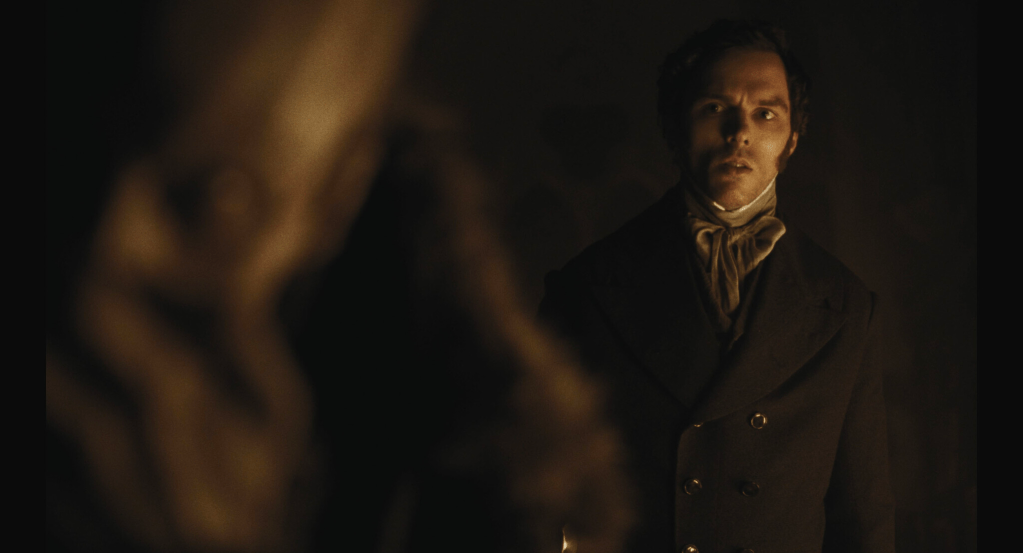

I struggled with whether to include this short film by one of my favourite filmmakers Kiyoshi Kurosawa ahead of more ambitious titles (like The Brutalist 2024), but ultimately this sinister snapshot of reality was impossible to shake. In a year, and what’s shaping as a decade defined by crucial filmmakers reflecting on their lives and creative work, Kurosawa used multiple 2024 projects to open a dialogue with his early and defining work, even going as far as remaking his 1998 film Serpent’s Path with the same name but in the French language.

In Chime, Kurosawa continues his pursuit into modern perceptions of evil and the malice of life through a brief lens into a culinary school, with a student seemingly driven mad by a noise no one else can hear. What happens next is a remarkable level of cinematic dread that burrows deep into your skin, taking up space in your soul. Kurosawa’s ability to communicate complicated ideas within the short film format is astounding, making this film a must-watch whenever it becomes more widely available.

9. Perfect Days

In a year stacked with esteemed filmmakers returning with a work deep in reflection of their first works, none felt as complete as Wim Wenders’ Japanese-language quotidian reflection piece Perfect Days. Centring on a Shibuya public toilet cleaner, Hirayama, performed by screen legend Kôji Yakusho, Wenders’ film reflects his global curiosity and evolving perspective on humanity through humour and grace. It will be a film I return to often in the coming years.

8. Janet Planet

Janet Planet is a film that knows the smell and crunch of autumn leaves outside a family home that can define a childhood. Annie Baker’s debut work in the cinema space (after years as one of Broadway’s great unsung playwrights), inhabits the in-between with an honest curiosity.

Centring on a wonderful child performance by Zoe Ziegler as the 11-year-old Lacy and her mother Janet (a gravity-altering Julianne Nicholson), Janet Planet is keenly aware of the way a child can refract the adults around them, revealing new parts of a parent and child that is rare in its respect for both sides.

7. Red Rooms

No film crawled under my skin more in 2024, where it continues to remain. While Canadian filmmaker Pascal Plante’s Red Rooms contains no violence, it is the most violently confrontational film you’ll encounter from the last year. At once a spiritual successor to David Fincher’s The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo (2011) and a keenly modern devolution of how the internet has isolated and festered our worst impulses, Red Rooms is one of the great underground discoveries of the year, a chilling interrogation into modern life through the lens of true crime, dark web violence, and modern voyeur culture.

At the front of the lens of the film is Kelly-Anne, portrayed by Juliette Gariépy as an all-time thriller character on the level of Patrick Bateman. A statuette beauty who spends her time modelling, crushing people in online poker, and obsessively attending the trial of Ludovic Chevalier (Maxwell McCabe-Lokos), a serial killer of adolescent girls who uploads his extreme violence to the dark web for those who wish to see, can. With Vincent Biron’s dexterous and compelling camera, we are intoxicated by a mesmerising oscillation between extreme unwatchability and an engrossing thriller, caught in a spiderweb where escape is too late. Achieves a lot from very little.

6. Evil Does Not Exist

The best score of the year can be found in Ryuichi Hamaguchi’s follow-up to this decade’s best film Drive My Car (2021), Evil Does Not Exist (more than halfway through the decade these lists should be beginning to solidify), with its elegiac jazz progressions that evolve into a haunting rapture from Eiko Ishibashi.

As a tale of eco-modernism that leaves room for the farcical ways contemporary metropolitan life seeks to corrupt what remains of the natural world which displays Hamaguchi’s breadth and quality as a writer. When consultants for a work retreat glamping company seek to operate within the small village of Mizubiki, they are confronted by an uncooperative community.

Like its overwhelming musical compositions, Evil Does Not Exist climaxes in a confounding but engrossing final moment that lingers and provokes long after you leave. Ishibashi and Hamaguchi are carving out a place as the composer-filmmaker collaboration which the industry should be measured up against.

5. Anora

The unexpected hit out of Cannes, making it the first American film to win the Palme d’Or since Tree of Life (2011) on top of being a Best Picture contender, Sean Baker’s eighth feature Anora is larger and broader than any film he’s made before while still capturing his uptempo yet sobering look into the contemporary American underbelly.

The modern chronicler of contemporary fringe America maintains his scepticism-bordering-on-cynicism about his homeland throughout his filmography, which is stretched to a compelling breaking point here. The internet has explained the film as a modern-day Pretty Woman (1990) by way of Uncut Gems (2019) with a Goodfellas (1990) like structure, but Sean Baker and star Mikey Madison are more interested in exploring how Ani is placed within different worlds than how the world changes her. Anora is a fully realised character that still carves out space to surprise us in moving and memorable ways.

4. The Seed of the Sacred Fig

A film with a backstory as compelling as its on-screen drama (filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof, the cast and creatives were forced to flee during production due to a warrant out for their arrest in Iran for filmmaking that goes against the regime), Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig speaks generationally about the modern Iranian moment through the language of family drama and genre filmmaking.

Through the use of social media footage from a recent student protest that turned violent—surprisingly a late addition in the editing process once they had fled the country—Rasoulof creates a certain surreality that arrives through this directness. This allows the simmering political drama to expand past the confines of the narrative into an explosive condemnation of authoritarian rule. While its final tonal shift won’t be for all audiences, it complicates and transforms the film into something larger and more elliptical than its humble and understated beginnings.

3. I Saw the TV Glow

In the days since the passing of the great David Lynch, much has been made about how modern cinema has increasingly lacked this effervescent feeling come to be known as ‘Lynchian’. But with the emergence of Jane Schoenberg and their second feature, I Saw the TV Glow in 2024, that essential Lynchian sensation that has defined indie filmmaking for 40 years has returned to breathe new life into our contemporary world.

With a close kinship to Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992) — in contention for best film of the 90s — I Saw the TV Glow ties 90s television fan nostalgia with the dissociative world of the adolescent trans experience that is willing to go to some deeply uncomfortable depths of the soul. Schoenberg’s modern reflection of the trans experience as a Lynchian world won’t place it within the awards season conversation, but alongside the extraordinary documentary No Other Land (2024), I Saw the TV Glow is the only essential film to arrive in theatres this year.

2. Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World

The funniest film of the year is also the hardest to wrestle with. Rade Jude is indie cinema’s great punk rocker, throwing rotten fruit at those that need it. After releasing what will eventually be seen as the definitive Covid satire, 2021’s Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, the Romanian satirist Jude returns to take aim at the capitalistic infrastructure of modern Bucharest, the gig economy, and the iron claw multinational corporations hold over even small production companies just trying to get by.

With Ilinca Manolache at the centre of his film as production assistant and part-time TikTok satirist Angela, Jude has the perfect muse for life in the Romanian capital, strained in every direction to get by, all for the financial security of a soulless multinational corporation, personified by a great cameo by Nina Hoss.

With its expansive 163-minute runtime, Jude holds many feet to the fire, concluding with a virtuosic yet simple long take for a workplace safety video which will prevent the families from suing the company for culpability, that both cements and brushes off its themes and frustrations like a poetic middle finger to the ruling class.

By culminating this long-form screed on modernity with a capitalistic nightmare version of Bob Dylan’s iconic music video for Subterranean Homesick Blues, with the family of a worker injured at work told to hold up blank pages meant to express their side of the story but will be written in post instead of in their own voice, Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World cements Jude as the modern satirist to compare all others to. No one is doing it like him, but I wish more tried.

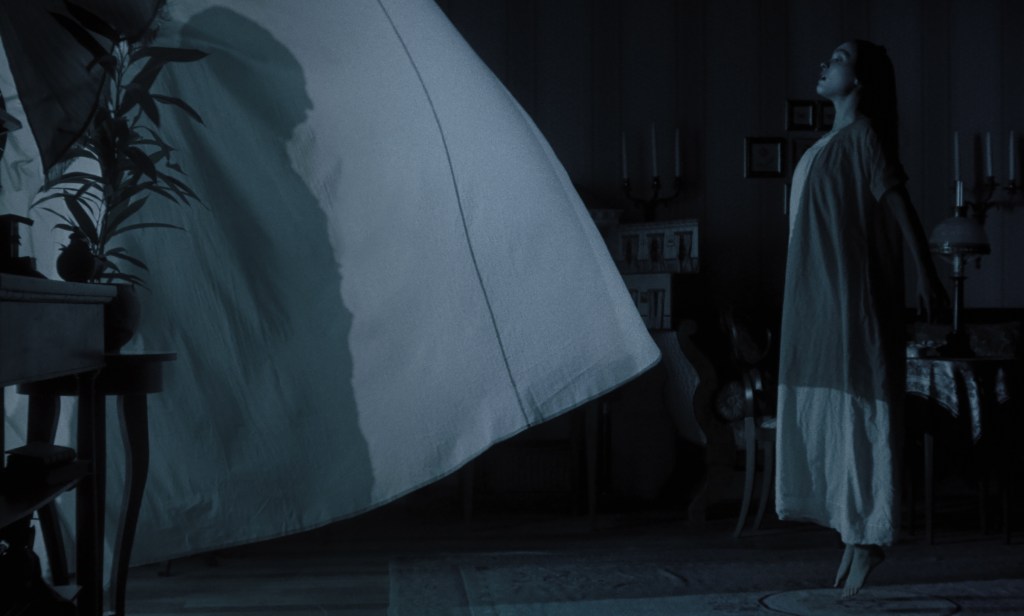

1. All We Imagine as Light

In a deep movie year with no real standouts like previous years have had, picking a number one was exceedingly difficult. That being said, no film expanded and deepened in my mind on rewatch as Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light. I was recently able to review this film properly since its showing at MIFF left me staggered. Kapadia’s soulful rendering of modern-day Mumbai is gorgeous and a must-see while it remains in theatres.

With a refined hand through documentary work, Kapadia flourishes in small moments. Whether it’s the embrace of a rice cooker given by a distant-slash-estranged husband working in Germany, or the small gesture of helping an older colleague move her things back to her old home after being wrongfully evicted, All We Imagine as Light embraces the aching emotionality of the quotidian, knowing these fleeting moments create a mosaic that reflects the light of human experience.

Honourable mentions: The Brutalist, Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus, Challengers, No Other Land.