27 years ago, Walt Disney Pictures took a massive gamble in distributing Toy Story, the world’s first feature-length film animated entirely with computer technology. Said film has since gone on to become a cultural touchstone, and the Emeryville-based crew that created it has morphed from a humble software firm to an entertainment juggernaut, its name as synonymous with animation as the corporation which acquired it.

The team at Rating Frames has been fortunate enough to witness the meteoric rise of Pixar Animation Studios first-hand – with our eldest writer being only a year older in age than Toy Story, we have never known a world without Pixar’s movies in it. Our earliest cinematic memories have been forged by their releases, which in turn have informed our love of the medium today.

Pixar made a return to theatres this weekend just past with Lightyear, breaking a two-year tradition of its pictures being released exclusively on Disney+. To celebrate this achievement, and his unflinching admiration for the company, our resident animation expert Tom Parry is ranking every prior Pixar feature from worst to best.

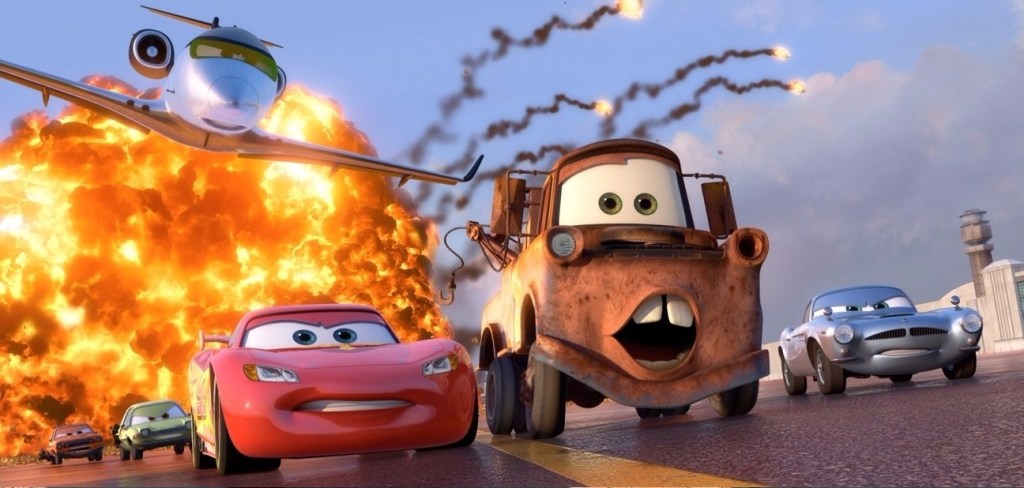

25. Cars 2 (2011)

This one’s appearance at the very bottom of our list should come as no surprise to anybody familiar with Emeryville’s filmography. With a nonsensical, chaotic story that makes its originator look passive, and a penchant for violence and destruction, this sequel is the let-down in an otherwise stellar family of high-achievers.

24. The Good Dinosaur (2015)

Despite being undeniably sweet and filled to the brim with gorgeous visuals – particularly those near-realistic landscapes – this seen-it-all-before screenplay squanders any potential by failing to build upon its (admittedly) clever premise. Ordinary by the standards of most; underwhelming by the standards of Pixar.

23. Cars 3 (2017)

Seeking to atone for the mess that was its predecessor, this threequel took the series back to its roots by opting for a more placid approach, and removing the juvenile antics – mostly. Although these changes are welcome, they result in a picture that feels too safe and lacks the magic of its stablemates.

22. Cars (2006)

Barely a nose ahead of the second and third Cars movies is the very product that inspired them. Some elements prove enjoyable, such as the tranquil driving sequences and surprisingly decent soundtrack; others are less so, like the infantile morals it seeks to impart on the viewer.

21. A Bug’s Life (1998)

One of the earlier releases from Pixar that has almost been lost to time, owing to the many quality productions in its wake. Needlessly mean-spirited and possessing a screenplay riddled with clichés, today it looks closer to another studio’s product than an early example of Pixar’s greatness.

20. Brave (2012)

A backward step for the esteemed folk of Emeryville as they follow the route usually taken by their superiors – telling a narrative about a princess in a medieval setting. But it’s saved from mediocrity by the Scottish backdrop, Patrick Doyle’s soundtrack and reasonably engaging conflict between the central protagonist and her mother.

19. Monsters University (2013)

The first and, to date, only prequel from Pixar, utilising the well-worn formula of the college movie and combining it with the ingenious concepts of its originator. Never reaches the emotional or intellectual heights of its contemporaries, but does have some amusing moments and a smart, thoughtful message.

18. Finding Dory (2016)

Andrew Stanton’s return to the deep-blue tugs at the heartstrings without ever reaching the heights of its highly-acclaimed and much-loved precursor. Nonetheless, it’s a delight, and worth watching alone for an utterly wild third-act.

17. Luca (2021)

Riding on an easy-going, carefree tone and possessing anime-inspired visuals, Enrico Casarosa’s Italy-set adventure is the most distinct feature of this bunch. A little too sweet and gentle when compared with its brethren, yet still an absolute charmer – one could almost describe it as catharsis in motion-picture format.

16. Onward (2020)

Nestled in the rich and imaginative world of New Mushroomton is a compelling, witty and warm tale about brotherly love, paired to an epic soundtrack of power ballads. Spoiling the otherwise-pleasing narrative is a trite conflict between siblings that a studio of this calibre should be avoiding at all costs.

15. Toy Story 4 (2019)

The least compelling entry in the Toy Story franchise, for it dispels its fantastic roster of deuteragonists and has rather disparate messaging. Even so, the screenplay is absorbing, the laughs hearty, the new characters likeable, the struggles relatable and the familiar voice-cast a reassuring hug from an old friend.

14. Incredibles 2 (2018)

A long-awaited, much-anticipated sequel that nearly lives up to the hype. Brad Bird’s movie carries over the superhero protagonists and multiple qualities of its predecessor, but forgets one key ingredient: an imposing, inimitable villain.

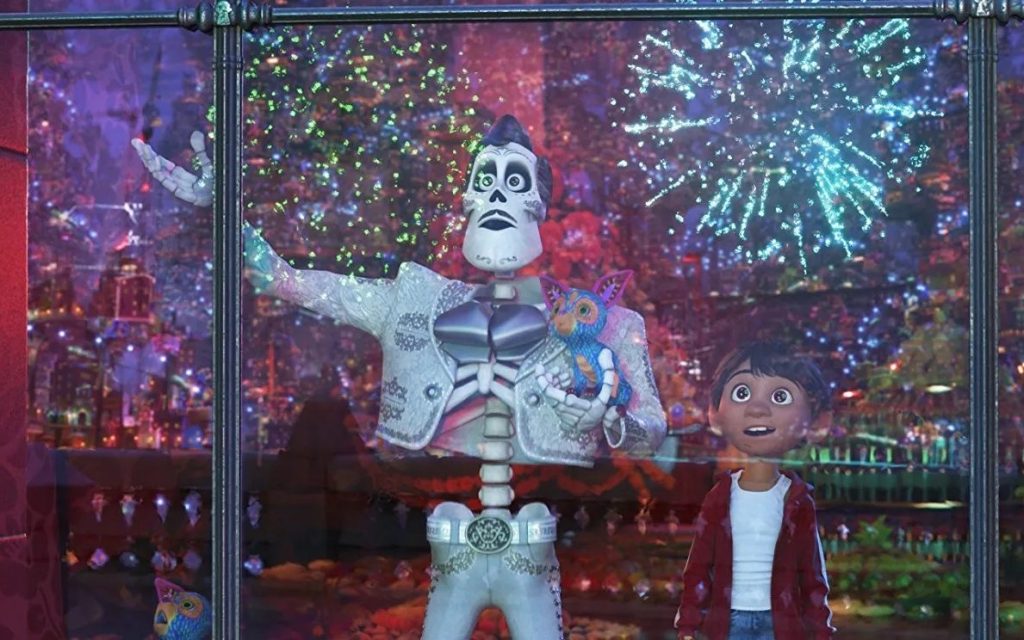

13. Coco (2017)

While comparisons with another Day of the Dead-themed animated feature, The Book of Life (2014) are inevitable, Pixar’s effort proves enjoyable in its own right due to the astonishing visuals and fabulous soundtrack. Only a hackneyed script hinders it from outright greatness.

12. Toy Story 3 (2010)

Never afraid to wrench a few hearts, Emeryville delivered its biggest tearjerker yet with this stirring threequel about everybody’s favourite playthings. Unfortunately, it’s spoilt by being a touch too dark at times, utilising the same themes as its precursor, and needing knowledge of the two prior films to be fully appreciated.

11. Monsters, Inc. (2001)

The directorial debut of Pete Docter takes a common trope – the belief that monsters terrorise children in their bedrooms at night – and applies its own unique spin to deliver a clever, heartfelt story. The characters are iconic, the dialogue endlessly quotable, the designs creative and the voice-cast peerless, though proceedings do get a bit outlandish.

10. Finding Nemo (2003)

Andrew Stanton’s ocean-faring debut feature possesses much the same strengths as Docter’s door-hopping tale, such as fantastic characters, quotes and voice-acting; yet Nemo gets the edge over Monsters for being the more grounded conflict. Plus, the blue of the deep sea helps lend a tranquil, serene tone.

9. Toy Story (1995)

After all these years, the movie that started it all remains a solid watch thanks to a timeless narrative and litany of distinctive personalities. If anything sours the experience, it’s the evident limitations of the technology available at the time. That, and the actions of the characters are quite extreme on occasion.

8. Turning Red (2022)

Released only a few months ago, Domee Shi’s coming-of-age comedy is already a certified classic for the studio. It’s also the most individual film of the bunch, containing slick designs, amusing slapstick gags, extroverted protagonists and an exuberance which is absent from most other Pixar movies.

7. Ratatouille (2007)

Its premise is bizarre and brilliant in equal measure – a rodent with a passion for gastronomy becomes a chef at his idol’s restaurant by using a lowly garbage boy as his vessel. But look behind the zaniness, and there will be found an investing conflict, stunning imitations of Parisian streetscapes, playful orchestrations and a monologue in the third-act that one never tires of hearing.

6. The Incredibles (2004)

Well-written protagonists facing a memorable, formidable villain. Detailed, superbly-rendered worlds. Quotes that stand the test of time. A brassy, catchy soundtrack from one of the industry’s all-time great composers. This isn’t just one of the best Pixar films, nor animated features; it’s one of the best superhero blockbusters ever released.

5. Soul (2020)

The least childlike product to emerge from Emeryville, which is no bad thing. Pete Docter’s pensive, adult-minded drama wins viewers over with its clever screenplay and exceptional soundtrack, proving that animation is a medium for all ages. It’s also, quite possibly, the only good thing to come from the year 2020, film or otherwise.

4. Wall-E (2008)

An ambitious, mesmerising piece of cinema that’s loaded with allegories and offers plenty of commentary of modern consumerism, yet at its basest level is a touching, charming tale about a tiny, lonesome robot who seeks a greater purpose in life. Visuals, music, sound editing and writing are all stellar.

3. Toy Story 2 (1999)

The first of many sequels and spin-offs from this company that set a very high benchmark for every production since. Aspects improved upon over the first Toy Story include better rendering, a more nuanced antagonist and some insightful ruminations on purpose and mortality, while the only irksome element is the pacing – it leans a tad toward the fast side.

2. Inside Out (2015)

Until the release of Soul, this was the most profound, mature and resonant feature in Pixar’s relatively short history. Don’t be fooled by the simplistic premise, loud colours and cartoonish designs of the main characters, for they mask a screenplay that’s clever and moving in the most unexpected of ways.

1. Up (2009)

The 2000s well and truly witnessed the peak of Pixar Animation Studios – it’s the decade that bore Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Ratatouille and Wall-E, five of the features which have drawn universal acclaim and come to define the company almost as much as the Toy Story franchise has. And at the very end of that decade came the picture that would top them all: Pete Docter’s Up.

The film has it all – a melodic orchestral soundtrack from Michael Giacchino; an emotion-filled montage of married life; endearing characters, both human and non-human; outstanding voice-acting from all involved; and a script that deftly fuses adventure, comedy, romance, fantasy and thrills. It is, quite simply, perfection in animated form, and deserves to be seen by everybody young and old.