Dune: Part Two preview screening provided by Universal Pictures

Few working directors have the capacity to deliver such audacious tentpole features like George Lucas and Sir Peter Jackson, and even fewer are able to do so authentically while ensuring that the end result is nothing short of spectacular. But that’s exactly what Denis Villeneuve has done with Dune: Part Two, his sequel to 2021’s Oscar winning Dune: Part One.

To call Dune: Part Two anything other than a generation defining Sci-Fi would be to undersell just how monumental an achievement the director has on his hands. Where Part One focused more on methodical world-building and planting the narrative seeds of Frank Herbert’s iconic novel (some might say in a much more trimmed down, thin fashion than expected), Part Two is all about scale and upping the ante.

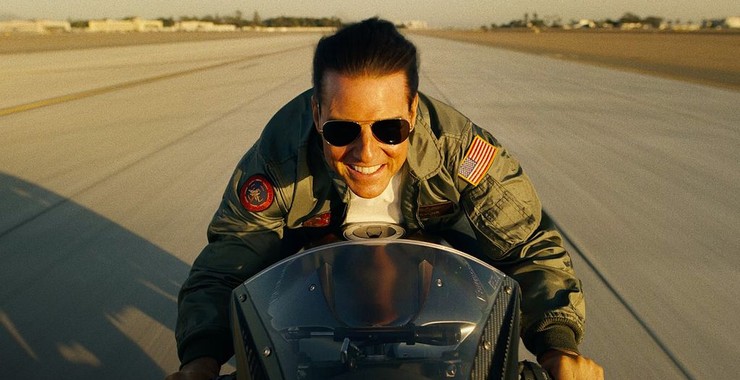

And it picks up almost immediately after the first film, where Paul Atreides (Timothee Chalamet) has found his way to the Fremen and is working towards building their trust, learning to assimilate in their ways, and realising his potential as a Messiah. There is seemingly more pandering this time around, with the first film having the skeleton of what is sure to become a trilogy, established, but lacking that extra flesh for why we should care about these characters, the Kwisatz Haderach or any of the novel’s deeper lore.

The care for those aspects all starts with Paul though, with his plight becoming increasingly refined by screenwriters Villeneuve and Jon Spaihts, who inject more oomph into the script. Paul is much more nuanced here, having had to grow up faster than he would have liked, especially now that the Harkonnens have reoccupied Arrakis (or Dune) and are actively pursuing spice. In turn, time is of the essence for Paul and the Fremen, especially as the Harkonnens edge closer to their hidden locations.

As a result the film places greater attention on the interplay between Paul and the Fremen. Fremen leader Stilgar (Javier Bardem) has become the guiding voice of reason who echoes the idea that the chosen one has arrived. He puts Paul through his paces via a series of trials that test out whether he truly lives up to all that was foretold. Whether that’s venturing out into the desert to overcome its harshness, battling the Harkonnens as they attempt to harvest spice, or riding a Shai-Hulud without guidance —there’s not shortage of incredible individual moments that both propel the narrative forward but also leave one in awe every time.

It’s in these moments that Part Two really shines and speaks to Villeneuve’s eye for detail and scale. It helps that the returning Greig Fraser (who won an Oscar for his cinematography for the first film) once again captures Dune’s deceptively beautiful vistas on a macro level, which allows that scale to shine through. Everything on Dune looks blown up in size which works to its advantage in creating this look of endlessness and enormity, a creative decision that speaks to the gravitas of the journey awaiting Paul. It’s all the more crystallised in the vibrancy of the desert colours, which further evoke that deceptive beauty of a world that will show you no mercy and swallow you whole.

For Paul, the only beauty that isn’t deceptive is that of young Fremen warrior, Chani (Zendaya). She helps him through his series of trials while continuing to hold her own as a character of interest that isn’t just sidelined to play second fiddle as a muse. Often she claps back against the popular opinion of Stilgar, and refuses to fall privy to what she sees as a cause that doesn’t exactly serve the interests of her people.

In fact, most of the female characters in Part Two play crucial roles in the film’s events, with Paul’s mother Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) embracing her destiny as the Fremen’s Reverend Mother. Princess Irulan (Florence Pugh) has a much smaller part in proceedings as the Emperor’s (Christopher Walken) daughter, serving more as a springboard for the plot and entry point to its politics rather than anything else, which isn’t a problem per se.

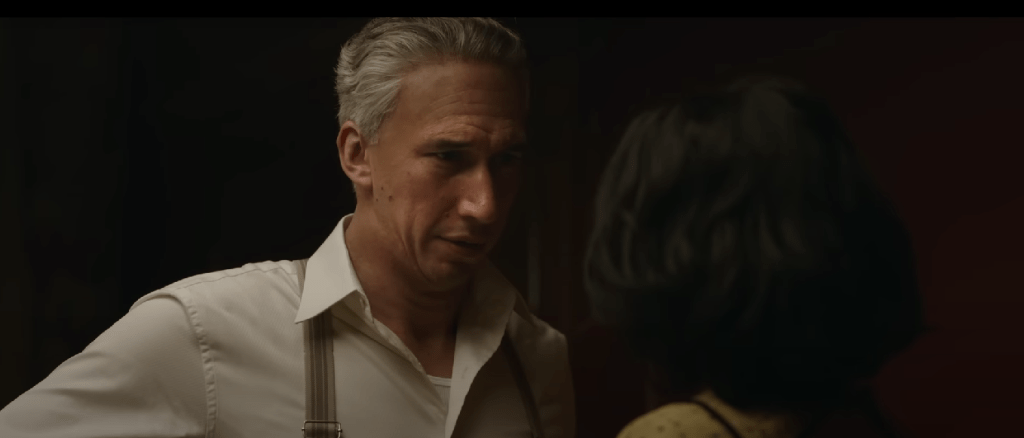

On the flip side are the Harkonnens, with the Baron (Stellan Skarsgård) returning in his hauntingly enlarged state alongside his incompetent nephew Rabban (Dave Bautista) who is continually being outsmarted by the Fremen as he tries to gather spice on Arrakis. But it’s Austin Butler’s portrayal as the Baron’s nephew, Feyd-Rautha, that is a particular standout; he comes across across as both raw and subtle, at once menacingly distant yet eerily close.

When the Fremen do lock horns with the Harkonnens, the result is always jaw-dropping set pieces with well choreographed fights that are supported rather than supplanted by those unique visual effects. The battles are also much easier on the eye compared to a majority of recent blockbusters, in that the action is discernible rather than messy. To top it off, Hans Zimmer’s score is also complimentary rather than excessive, with his use of drums and sharp crescendos aptly suiting the various cultures and moments (I had literal goosebumps at moments as the soundscape reverberated through my seat and being).

If there was to be a shortcoming it would be that the closing sequence rounds off rather abruptly. At various points throughout the film I couldn’t help but wonder how Villeneuve would bring everything together as the finish line was becoming clearer and closer to the end. However, he had always said that this was a continuation rather than a direct sequel, and that aspect is felt, even though audiences might be left wondering by the end —with some threads left hanging.

That said, there are few directors who can create a spectacle at such a scale while leaving their own mark and remaining faithful to the source material. Dune: Part Two takes the best parts of the second half of Herbert’s novel —allegory and all— and serves them up in a digestible, refined and spectacular result that is reminiscent of some of the best sequels (or continuations) in cinema history.

Dune: Part Two opens nationally from the 29th of February.