With 2023 drawing to a close, Rating Frames is looking back at the past twelve months of cinema and streaming releases that have come our way. In the third of our series of articles, Arnel Duracak is taking a look at his ten favourite films of the year that was.

In what was a year jam-packed with incredible film titles, a myriad of legendary directors continuing to deliver the goods, newcomers making their mark, and strikes that led to several delays for other anticipated releases, I only wish that I had spent more time in front of a silver screen.

Alas, I ventured to Europe for a good few months which limited my access to key titles early on in the year (though I did see Michael Mann’s 1995 classic Heat at London’s Prince Charles Cinema), but I was lucky to be able to witness some of the year’s best films at the cinema in the second half of 2023. There have been multiple other titles that I wish I had seen before the end of 2023 –––The Holdovers, Poor Things, Ferrari (which I will be reviewing for the site soon), to name a few––– but nonetheless I am satisfied with what I was able to see. Here’s to a 2024 with more of the same, happy watching!

10. Wonka

As I was looking at my ongoing 2023 ranking list, it turns out Wonka made the cut.

While I am a bit surprised, this film felt like the most deserving 3.5 star film from 2023 for me. It neither rocked my socks nor did it live up to the brilliance of Paul King’s modern classic Paddington 2 (2017), but my bar was set rather low for this title if not for the fact that it felt like an unnecessary foray into the background of one of cinema’s strangest characters, then definitely because I just wasn’t all that interested (Darcy will attest to that).

But being a King and Simon Farnaby screenplay, Wonka felt both fresh and unique, owing to the fact that it was imbued with the zany British humour that Paddington 2 excelled at, had an all-star cast who thrive as misfits and are just a joy to be around, contained some catchy musical set pieces (‘Scrub Scrub’ being a particular highlight), and never felt like it was trying to follow in the footsteps of the other two Willy Wonka films.

My only gripe would be that Wonka himself was less interesting as a character than any of the side characters. Whether or not that was because Chalamet’s performance was a bit overly boisterous or because 90% of the core cast meshed well with the British comedy by comparison, but Chalamet’s no Gene Wilder here (maybe for the best).

9. Oppenheimer

In what is perhaps Christopher Nolan’s most accomplished film for many (2008’s The Dark Knight still takes the cake for me), Oppenheimer is a magnetic feat in filmmaking that only Nolan could deliver at such a scale.

I’ve never been a big fan of the way that he writes dialogue, and Oppenheimer isn’t different in that regard for me as it tries to balance more heartfelt, interpersonal connections with more heavy handed themes and technical language (ultimately tailspinning into some less than convincing, at times eye-rolly back-and-forths). However, for a three hour film that is about one of history’s darkest periods, it flows rather well with crisp editing, excellent performances all around, a moody but effective score, and direction from Nolan at the peak of his powers. The film’s climax is one of the most cinematic this year and once cements Nolan’s status as the king of IMAX.

At the time of writing, it’s been about an hour since Oppenheimer swept up the Golden Globes, and if that isn’t a testament to just how deserving this film is to be on anyone’s top 10 list, then I’m sure the Oscars will have something to say about that.

8. Asteroid City

In what is a film of layer upon layer upon layer, Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City is a film I’ve accepted I just have a love-hate relationship with.

Anderson, of course, probably has the most identifiable visual style of any working director at the moment, and he once again delivers incredible vistas in this desert doll-house diorama showcase. Asteroid City is also his most self-reflexive film, both on the art of being a storyteller and on the process leading up to the camera rolling.

Artifice and reality intersect on multiple occasions, with the film playing out through a series of chapters that pull you into the world itself, and then pull you back out to take a glance at how everything is coming together. At times the film can be beguiling, especially if you aren’t familiar with his previous stuff, but it’s also a rewarding insight into art of being a storyteller.

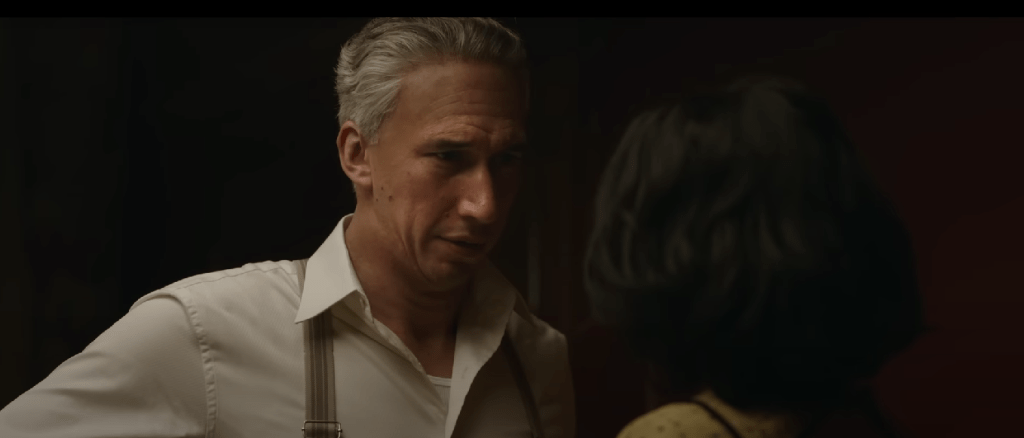

7. The Killer

Many (and by many, I mean Letterboxd users) have called David Fincher’s The Killer his most introspective, meditative film on the craft of doing your job, taking pride in your work and thinking you’re doing it so well to the point of perfection. I just think it’s his most comedic.

Michael Fassbender stars as the straight-faced, emotionless hitman who screws up a hit and now has to clean up his tracks and those that might wish to take him out for his shortcoming.

The Killer is a great study on the dissolution of identity, of a man coping with his inner thoughts and dismissing all empathy for those that don’t deserve it because he knows the game he’s playing and the players involved. As mentioned, I also think it’s a comedy or at the very least, unintentionally funny especially with various internal monologues by the character, describing what he sees and feels, that are followed by sharp interruptions.

While this isn’t Fincher’s best film or even in his top three, it’s a safe but well executed crime thriller that will satiate the desire of hardcore Finchonians who would wish to see him return to similar stories.

6. Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One

I’ve continually been surprised by just how good each Mission Impossible film has gotten.

Christopher McQuarrie and Tom Cruise are like each other’s yin and yang as they seem to have found common ground since their first collaboration on Jack Reacher (2012) to the point where they’re willing to push the boundaries of what’s achievable on film at such a scale. Cruise especially is no stranger to putting his body and life on the line for an awesome shot, and in Dead Reckoning Part One there is everything from that iconic plummeting bike sequence off the top of a cliff to the creation and destruction of a whole train.

While Dead Reckoning Part One is pipped only by Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018) in the franchise in terms of scale and death defying moments, it is pure action cinema that knows no bounds. I’m keen to see what Part Two will have to offer.

5. Past Lives

Celine Song’s debut feature is the sort of film that sneaks up and catches you off guard if you’re not prepared for its candid depictions of everyday people doing this thing we call life, and it leaves you feeling either optimistic or a tad wrecked by the time it’s over.

I generally gravitate towards fantasy, action and romance films, and I was pleasantly surprised that while this is a film about young love and looking back to move forward, it’s ultimately a film about reconciliation and friendship.

Song’s film cleverly captures how time passes in an instant; we try to hold on to the high points as much as we can, we’d put them in a bottle if we could, but that’s not how life works. In other words, things happen for a reason, but that doesn’t mean we have to forget the past, but rather learn to live with the present reality that we’ve been given.

The film is ultimately anchored by Greta Lee, Teo Yoo and John Magaro who form the emotional centre that allows Song to deliver this story as effectively as she does.

4. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

Across the Spider-Verse was one of the releases that I missed on the big-screen after going to Europe and only saw towards the close of the year on Prime Video.

I say that with a degree of sadness as this sequel to the Oscar winning hook-out-of-nowhere, Into the Spider-Verse (2018), absolutely floored me in just how creative it was in utilising the key moments of past Spider-man films and flipping them on their head to deliver an original, engaging, emotional and downright fun two and a half hours. The trio of writers, Phil Lord, Christopher Miller and Dave Callaham clearly understand this world and its characters, and it shows in all of its vibrancy.

Much has been said on the animation style of these films, and it once agains results in a colourful and unique display. Another Part Two I am ever so keen to see.

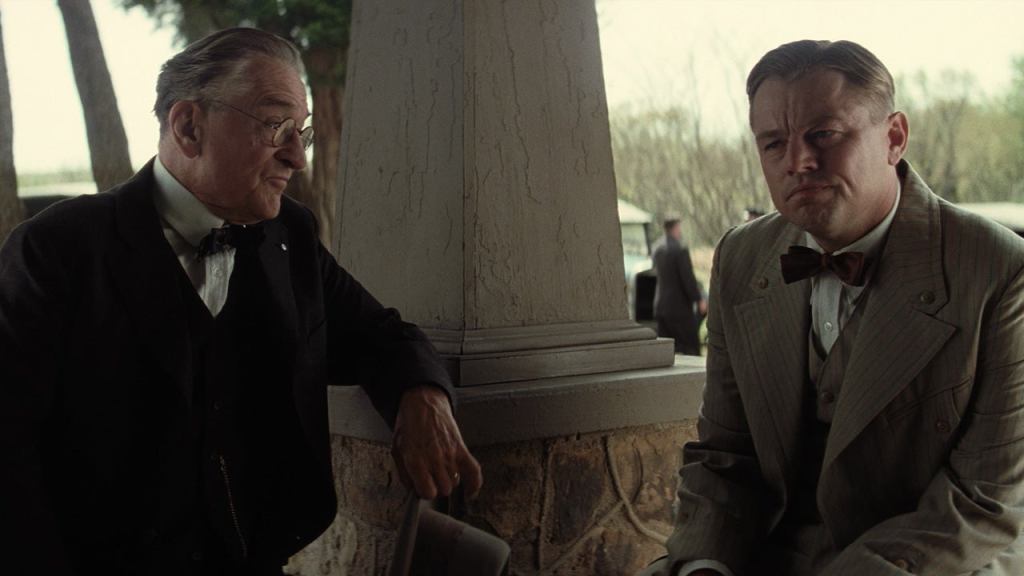

3. Killers of the Flower Moon

Martin Scorsese has been there, done that and gone back again, but even I couldn’t believe the brilliance I was seeing with Killers of the Flower Moon ––– even though brilliance is what we’ve always known with this cinematic titan.

Killers of the Flower Moon is another film that passes the three hour mark this year, but if it went for another three, I don’t think there would be many complaints. And that’s owed largely to just how precise Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing is, which paces the film very tidily with no loose moments that don’t add up to a wider whole.

It’s also a testament to Scorsese’s brilliant direction and he and Eric Roth’s approach to the screenplay which they flipped on its head and decided to tackle from an inside point around the film’s perpetrators. The result is one where we still see all of Scorsese’s signature mobster embellishments and themes of betrayal, ambition and greed, but they’re repurposed in a more Western setting and allowed to simmer for the film’s lengthy runtime.

I’ve said it elsewhere, but Killers of the Flower Moon feels like the sum of all the best parts of Scorsese’s oeuvre. By that I mean not just in the little tell-tales and visual cues that scream Scorsese, but more in terms of how this film balances tension, develops character, incorporates louder moments with more muted ones, communicates more heavy handed themes like greed and corruption in a digestible way, and all while feeling fresh in the process.

The fact that this isn’t his magnum opus tells you everything you need to know about him, so let’s enjoy this legend while he’s still around.

2. (How Do You Live?) The Boy and the Heron

From one legend to another, Hayao Miyazaki’s decision to un-retire and make The Boy and the Heron was met with wide gasps, especially since The Wind Rises (2013) felt like the perfect capstone to his illustrious career.

Yet there was clearly some unfinished business in the director’s life that he no doubt felt compelled to express, and in his latest he once again takes a deep dive into the phantasmagorical through various creatures, concoctions and imagery, but with existentialism at the forefront.

The Boy and the Heron might well be seen as Miyazaki coming to terms with the limitations of the physical form and seeking out answers, or at least seeking to provide certain tools that might lead to the answers around what this thing called life is all about. Darcy has described the film as a “deep meditation on life and grief” and I think that’s the basis for what Miyazaki is going for here, along with the idea of carving something from nothing and doing your best to hold it together for as long as you can.

For the young character Mahito at the centre of it all, he is there to try and help take this bleakness and turn it into something redeemable now that his uncle (a very obvious injection of self from Miyazaki), cannot. It’s almost a futile request as everything around him crumbles, but it’s enough to believe he will take this with him in his own life and attempt to bring some order to it that way.

1. John Wick: Chapter 4

It feels like a millennium ago that I saw the fourth instalment in Chad Stahleski’s thriving John Wick franchise, and yet nothing this year has toppled it from the peak of my list.

Don’t get me wrong, any of my top three could just as easily be sitting in pole position, but Stahelski’s final John Wick film is a sensory overload that I feel like was made for me. Shay Hatten and Michael Finch’s ability to up the ante and deliver a screenplay that not only ties everything from the first three films together, but adds some more and then blows everything out of the water in the third act is truly mind-boggling (it’s a crime they weren’t nominated at the Golden Globes for Best Screenplay).

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. I’ve long praised Stahelski for his understanding of actors and his ability to stage fight scenes, but in John Wick Chapter 4 he has once again managed to blend hand-to-hand combat and bullets galore with an appreciation for more grounded storytelling and the recognition that John Wick is the emotional anchor of this film even when he’s engaged in tense situations.

He’s not just a two-dimensional assassin or someone simply out for revenge, and Chapter 4 makes it clear that moving forward requires sacrifice. And this franchise has always been able to introduce anti-heroes and antagonists that are just as layered as Wick because they occupy the same space, under the same oversight, guided by the same principles ––– Wick just has the courage to stand against the system that has nurtured him and recognise the virus its rotten roots are spreading.

It feels like a fairytale ending that echoes the practicality and originality of Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) while standing out from anything else that has been released since Fury Road in the action genre. I can safely say I am eagerly anticipating Stahelski’s adaptation of Ghost of Tsushima.

Honourable mentions: Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, Babylon (a 2023 release in Australia)