Arnie, Darcy and Tom recap the 95th Academy Awards, including everything from Ke Huy Quan’s extraordinary journey to win the Best Supporting Actor award; his fellow cast member Michelle Yeoh’s Best Actress win; the biggest winner of the night in Everything Everywhere All At Once; All Quiet on the Western Front‘s underdog wins; and Brendan Fraser’s Best Actor win to cap off his run of wins — we have it all.

Tag: movies

95th Academy Awards: Predictions

It’s the most wonderful time of the year if you’re a cinephile, and it’s just around the corner.

Yes, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Night of Nights —otherwise known as “The Oscars”— will be taking place this Monday morning, March 13th (Naarm time) and the team at Rating Frames is as excited as ever.

As they did last year, our three resident critics have made their predictions as to what, or who, will be victorious in all 23 categories.

Below are the films that Arnel, Darcy and Tom are predicting will walk away with a coveted statuette at the 95th Academy Awards, and their personal vote, in each category.

Best Picture

What will win // What deserves to win

Arnel: The Fabelmans // The Fabelmans

Darcy: Everything Everywhere All at Once // Tár

Tom: Everything Everywhere All at Once // Everything Everywhere…

Best Director

Arnel: Steven Spielberg (The Fabelmans) // Steven Spielberg (The Fabelmans)

Darcy: Daniel Kwan & Daniel Scheinert (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Steven Spielberg (The Fabelmans)

Tom: Daniels (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Martin McDonagh (The Banshees of Inisherin)

Best Actor

Arnel: Brendan Fraser (The Whale) // Colin Farrell (The Banshees of Inisherin)

Darcy: Brendan Fraser (The Whale) // Paul Mescal (Aftersun)

Tom: Brendan Fraser (The Whale) // Colin Farrell (The Banshees of Inisherin)

Best Actress

Arnel: Cate Blanchett (Tár) // Cate Blanchett (Tár)

Darcy: Cate Blanchett (Tár) // Cate Blanchett (Tár)

Tom: Michelle Yeoh (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Michelle Yeoh (Everything Everywhere…)

Best Supporting Actor

Arnel: Ke Huy Quan (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Brendan Gleeson (The Banshees of Inisherin)

Darcy: Ke Huy Quan (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Ke Huy Quan (Everything Everywhere All at Once)

Tom: Ke Huy Quan (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Brian Tyree Henry (Causeway)

Best Supporting Actress

Arnel: Angela Bassett (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever) // Kerry Condon (The Banshees of Inisherin)

Darcy: Angela Bassett (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever) // Kerry Condon (The Banshees of Inisherin)

Tom: Jamie Lee Curtis (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Stephanie Hsu (Everything Everywhere All at Once)

Best Original Screenplay

Arnel: Martin McDonagh (The Banshees of Inisherin) // Martin McDonagh (The Banshees of Inisherin)

Darcy: Martin McDonagh (The Banshees of Inisherin) // Todd Field (Tár)

Tom: Daniels (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Martin McDonagh (The Banshees of Inisherin)

Best Adapted Screenplay

Arnel: Sarah Polley (Women Talking) // Sarah Polley (Women Talking)

Darcy: Sarah Polley (Women Talking) // Sarah Polley (Women Talking)

Tom: Sarah Polley (Women Talking) // Rian Johnson (Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery)

Best Animated Feature

Arnel: Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio // Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio

Darcy: Turning Red // Turning Red

Tom: Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio // Turning Red

Best International Feature

Arnel: All Quiet on the Western Front // All Quiet on the Western Front (ideally, none)

Darcy: All Quiet on the Western Front // The Quiet Girl

Tom: All Quiet on the Western Front // All Quiet on the Western Front

Best Documentary Feature

Arnel: Guess answer: Fire of Love // Fire of Love

Darcy: Navalny // All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

Tom: Fire of Love // Fire of Love

Best Documentary Short Subject

Arnel: Guess answer: Haulout

Darcy: Haulout

Tom: How Do You Measure a Year?

Best Live-Action Short

Arnel: Guess answer: Le Pupille

Darcy: Le Pupille

Tom: Le Pupille

Best Animated Short

Arnel: Guess answer: The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse

Darcy: The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse

Tom: The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse

Best Original Score

Arnel: Justin Hurwitz (Babylon) // Justin Hurwitz (Babylon)

Darcy: Justin Hurwitz (Babylon) // Justin Hurwitz (Babylon)

Tom: Volker Bertelmann (All Quiet on the Western Front) // Justin Hurwitz (Babylon)

Best Original Song

Arnel: “Naatu Naatu” (RRR) // “Hold My Hand” (Top Gun: Maverick)

Darcy: “Naatu Naatu” (RRR) // “This is a Life” (Everything Everywhere All at Once)

Tom: “Naatu Naatu” (RRR) // “Hold My Hand” (Top Gun: Maverick)

Best Sound

Arnel: Top Gun: Maverick // Top Gun: Maverick

Darcy: Top Gun: Maverick // The Batman

Tom: All Quiet on the Western Front // Top Gun: Maverick

Best Production Design

Arnel: Babylon // Babylon

Darcy: Babylon // Babylon

Tom: Elvis // All Quiet on the Western Front

Best Cinematography

Arnel: Roger Deakins (Empire of Light) // Roger Deakins (Empire of Light)

Darcy: Roger Deakins (Empire of Light) // Florian Hoffmeister (Tár)

Tom: Mandy Walker (Elvis) // James Friend (All Quiet on the Western Front)

Best Makeup and Hairstyling

Arnel: The Whale // The Batman

Darcy: Elvis // Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Tom: The Whale // The Batman

Best Costume Design

Arnel: Shirley Kurata (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Shirley Kurata (Everything Everywhere All at Once)

Darcy: Shirley Kurata (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Shirley Kurata (Everything Everywhere All at Once)

Tom: Catherine Martin (Elvis) // Ruth Carter (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever)

Best Film Editing

Arnel: Paul Rogers (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Paul Rogers (Everything Everywhere All at Once)

Darcy: Paul Rogers (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Paul Rogers (Everything Everywhere All at Once)

Tom: Paul Rogers (Everything Everywhere All at Once) // Eddie Hamilton (Top Gun: Maverick)

Best Visual Effects

Arnel: Avatar: The Way of Water // Avatar: The Way of Water

Darcy: Avatar: The Way of Water // Avatar: The Way of Water

Tom: Avatar: The Way of Water // Top Gun: Maverick

Pearl Stands on Her Own

“Please lord, make me the biggest star the world has ever seen”, our heroine Pearl (Mia Goth) pleads each night before bed, accompanied by a garish string accompaniment that draws immediate comparisons to the early colour cinema. A skilled director of pastiche, Ti West has crafted a Douglas Sirk-styled film within the dark and gory world he has created with muse Goth, that is sure to thrill old and new fans alike. Immediately following the release of one of 2022’s best horror films, X, it was announced West and Goth will be creating a trilogy surrounding these characters, here with the prequel Pearl (2022), and concluding with MaXXXine (2023), all following Goth’s characters.

Set in 1918 Texas during the Influenza pandemic, Pearl is the only child of a German immigrant family. Pearl’s father (Matthew Sunderland) is infirm, laying the burden of survival in a trying time with Ruth (Tandi Wright), Pearl’s domineering mother who needs to get her daughter to help out around the farm. Pearl, however, is desperate to become a silent film star and dancer, sneaking off to the picture house every opportunity she gets.

Pearl’s love of cinema and desire to be a star is established in X, something that ties her to Goth’s other character Maxine in that film, which is deepened here. Pearl is never more joyful than when she is at the picture house, watching the newest dancing features. Goth and West craft such an empathetic and archetypal image of a budding star hoping to break out, that her budding malevolence is allowed to boil under the surface.

The film is aware its greatest strength is a close-up of Goth’s expressive face, a cinematic world into itself. Enough can’t be said about Goth’s commitment to the performance of this character, beginning in X but truly flowering here to create a singular horror cinema performance. You can immediately feel Goth’s co-writing credit in the character, similar to Hunter Schaeffer’s co-writing credit in the Euphoria (2019) Covid special, Fuck Anyone Who’s Not a Sea Blob (the artistic peak of the show), where a performer has a psychic connection to their role that tears through the screen.

The saturated, Wizard of Oz (1939) inspired-yet-repressed world that Pearl inhabits can grow tiring at stages, but the final act is such a showcase for Goth’s magnetism as a performer and writer, that the film leaves you satisfied. West’s films often have an issue of peaking early through his deft skill at creating tension and dread compared to his bloody finales, an issue absent in Pearl.

The film’s setting within the Influenza pandemic whilst being a Covid-produced film has a simple charm to it, with all crowds in masks and characters bemoaning the difficulties of recognising people in them. Pearl’s yearning to be out of the isolation of her farm during this pandemic is a more relatable experience than you’d expect to come out of this film.

Pearl is a unique prequel in that it has the potential to be viewed before the original film, X, due to its focused character study of Pearl, a character you leave the first film aching for more details on. West and Goth feel acutely aware of the aspects audiences were craving more from in X, namely the Pearl character and a further relishing of Goth’s unique screen presence.

Where X focuses on its wide ensemble and 70s environment, Pearl is very much a character study. Aside from a compelling performance by Tandi Wright as Ruth, Pearl’s mother, we are not given many deeply written side characters, allowing the audience to narrow their attention to our star. Wright and Goth have a similar dynamic to Spacek and Laurie in Carrie (1976), a foundational text for the film, particularly in its latter stages. While West is focusing on the juxtaposition of the Cinemascope aesthetic with the gore, the true dynamism is achieved through Goth’s varied performance that gets stymied by Wright’s hard-lined determination to survive their struggling lives. The real climax of the film is not a gory showstopper like in X, but the culmination of Pearl and Ruth’s resentments colliding at a family dinner.

The West trilogy is soon to be completed with the upcoming MaXXXine (2023), the first A24 trilogy. Following on from the events of X, this second entry in this quickly produced franchise is a unique world that has been crafted by a pair of oddball filmmakers in West and Goth that is refreshing in the world of IP drudgery we find ourselves in the never-ending middle of.

Pearl is in theatres from March 16th.

The Films of Michael Mann, Ranked

No one manages to blend crime and action on the big screen quite like Michael Mann. From the sprawling cityscapes that act as their own character, to the attention-to-detail with each and every aspect of production, Mann’s films are distinctively his own. It seems fitting then to look back on his stellar oeuvre and try and rank his titles based on my sentiment towards them at this moment in time. This is especially the case following his recent novel and sequel to the iconic Heat (1995), which he co-wrote with Meg Gardiner, and leading up to his Adam Driver-led, Enzo Ferrari biopic, Ferrari (2023).

Of course, like with any list, opinions are different and feelings towards films change as time goes by and depending on where in your life you find yourself. But for now, these are his films ranked from worst (if you can call them that) to best:

11. The Keep (1983)

Whether it’s due to the fact that large chunks of this film were cut out, or because it’s the least Mann-esque title on the list, The Keep is what I like to call Mann’s brain fart.

His second feature following the brilliant Thief (1981) represents his first and clearest (as there are elements of this in his true crime thrillers) foray into the horror genre. It’s a film plagued by bland and uninspired performances; a nonsensical narrative involving Nazis, a devilish entity, a supernatural Scott Glenn and one of the strangest but best sex-scenes you’re likely to see in a Mann film or otherwise; an interesting production design; and a pretty neat synthy score by Tangerine Dream.

Given Mann has disowned the film because of Paramount’s treatment of it, one can only imagine what the unreleased director’s cut had in store — we can only hope it graces out screens someday.

10. Manhunter (1986)

Many might find my ranking of Manhunter to be completely against the grain, but this thriller revolving around capturing a psychotic serial killer just never resonated with me on a narrative level like some of the other titles on this list (and I still gave it 3.5/5).

Manhunter focuses on FBI agent Will Graham (William Peterson), a detective who’s come out of retirement to help locate an elusive serial-killer with strange motives. His past experiences hunting figures like Hannibal Lecter (a subtle performance by Brian Cox) means he’s the perfect guy for the job.

Manhunter uses Will and the serial killer he’s hunting to create an interesting parallel between the mind of a psychotic man and the man capable of catching him. Its use of home video and the focus on truly seeing almost posits that these two men aren’t so different in how they see the world, but to different ends and outcomes.

Whether or not I was expecting a more conventional voyeuristic mystery-thriller in the way that Se7en (1995) or Rear Window (1954) are —where the killer feels like they’re an arm’s length away, only for the satisfaction of catching them to be snatched from you— is difficult to say (perhaps that’s what people love about this?), but I found myself at a crossroads by the third act. I hope my opinion changes on a second viewing.

9. Ali (2001)

On the surface, a film about Muhammad Ali seems like the farthest thing from a Michael Mann joint. There’s no mesmerising cityscape, no sirens or gunfire, no real suspense in the way that his crime films create suspense, and the subject matter doesn’t exactly scream ‘Michael Mann’.

But this film about the greatest boxer of all time works because of Mann’s interest in figures that don’t play by the rules. Specifically, Ali focuses on the period of time between Ali’s (Will Smith) first major heavyweight bout, the court case filed against him for refusing conscription for the Vietnam War, and his famous win against George Foreman to reclaim the heavyweight title.

Ali’s unilateral decision to not be conscripted was momentous for the fact that he was the heavyweight champion of the world, and making such a decision could affect his ability to box in his prime (which it did). He also reinvented who he was by changing his name and living on his own terms — a staple of Mann characters, but for different reasons. Often his characters are trying to protect others from who they truly are whereas Ali was trying to break away from the branding that others (white slavers) had given him and his people centuries ago.

The opening 15 or so minutes are also arguably Mann’s most compelling in the way that he establishes character, creates purpose and builds tension. At times there’s a suddenness to proceedings where the film makes abrupt leaps in time between the court case announcement, the Joe Frazier fight, and the George Foreman fight, but overall Ali is a portrait of one man’s journey to becoming in the face of adversary.

8. The Last of the Mohicans (1992)

Along with The Keep, The Last of the Mohicans represents a different sort of Mann.

Like with Peter Jackson’s first film experience with the classic King Kong (1933) and his eventual reimagining of that classic on his own terms in King Kong (2005), Mann’s first vivid film memory was of 1936’s The Last of the Mohicans.

Helmed by Daniel Day-Lewis as the adopted Mohican, Hawkeye, this period piece about everything from the damning effects of bureaucracy to the Tarzan-esque romanticism of the love affair between Hawkeye and Cora Munro (Madeleine Stowe), is the first Mann film to create a sense of scale that would have greatly shaped the way he approached his later films.

By that I mean Mann finds a balance between showcasing the wide and beautiful terrain of a primeval America against the harshness of the looming modernisation that threatens its existence. This translates onto how the characters react to each other, whether it be through Magua (a mesmerising Wes Studi) and his desire for revenge against the British (for what they took from him) as well as his forward thinking to help his tribe, or through the loud and rampant battle at Fort William Henry that threatens the peace of the land.

Guided by one of the greatest scores of any film ever by Trevor Jones and Randy Edelman which at once evokes hope and sadness, picturesque vistas, and gripping direction that never falters, this Mann-epic is Mann at his most untethered.

7. Public Enemies (2009)

When it comes to famous outlaws, there are few that are as iconic as John Dillinger, especially given he was a man who wasn’t interested in stealing from regular people, but the state itself.

That’s partly why he’s the perfect historical figure for a Michael Mann film given his self-defined approach to life.

Public Enemies follows Dillinger (Johnny Depp) as he makes prison escape after prison escape, continuously evading capture and robbing banks before finding an added purpose in life in the form of one French-American, Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard).

Like all of Mann’s anti-heroes, Depp’s Dillinger is charming and elusive all at once. He’s a character infused with an aura of mystique that Depp delivers with the casual suave that his own image beyond the screen has maintained.

But it’s in the reimagining of the period through a digital lens where Public Enemies really excels. The moody greys, dark passages and almost colourless world are so striking here that it creates a more profound hyper-realism — almost bringing the 1930s to life in a way that shooting on film wouldn’t.

6. The Insider (1999)

A film about a man’s grapple with doing what’s morally right or being forced into silence by forces greater than him; The Insider, in true Mann-style, is an exercise in patience — in waiting for the right moment to make a move before it’s too late.

Unlike Mann’s other thrillers though, The Insider doesn’t have vans of heavily armed forces hiding around the corner, but it instead puts its faith in the truth overcoming the odds. That truth is in the form of former tobacco chemical scientist, Jeffrey Wigand (Russell Crowe) and the 60 Minutes producer looking to help bring his story to light, Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino). The odds are the Brown and Williamson Tobacco Company who are trying to keep Jeffrey, and this story around what really happens to tobacco, silent.

Guided by Mann’s brilliant direction, a well-crafted script by Mann and Eric Roth, and a standout performance from Al Pacino in an unfamiliar but equally familiar performance, The Insider paints a perplexing portrait of the lengths to which vindictive multi-billion dollar organisations will go to in order to supress information. It brings various parties with differing interests together, and creates a wide web of uncertainty for all involved — with no clear contingencies, but everything to lose for everyone involved.

5. Blackhat (2015)

Michael Mann’s most recent film feels like a sum of all of his best parts (it’s also been eight years since it was released!).

The film follows hacker Nicholas Hathaway (a career-best performance from Chris Hemsworth) who, after a series of awry events happen by an unknown source, is released from prison for the purpose of helping discover the person behind these events.

Blackhat is where ideas meet, characters converge, and where the tangible coalesces with the intangible.

In a similar way to Manhunter (but without the straining of classic thriller conventions) and Heat, this film once again depicts two sides of the same coin — Hathaway as the hacker-turned-FBI collaborator, and the unknown hacker blowing up coolant pipes and infiltrating wall-street. One is front and centre for the audience, while the other is kept faceless. While their intentions are different, they occupy a similar space like almost all of Mann’s characters do, but Blackhat is different to his past films because of how it bridges the characters worlds together and carries and communicates messages.

Mann uses modern technology to create a divide (the intangible), and forces his characters to embrace human interaction and connection (the tangible) if they are to overcome this threat.

His portrayal of the L.A. and Hong Kong maze of buildings and their bright lights speaks to the lack of personality or distinguished features in these settings, which fizzles down to the people who fade into each other like ones and zeros. It’s a wider critique on getting lost in the masses at a macro level, and getting lost in the code on a micro level.

Hathaway is the vessel Mann uses here to try and break through the code and by extension, this front that a world lacking real connections, has maintained — with Hemsworth using his size and stature to brilliant avail.

The closing sequence sees Hathaway concoct weapons and armour out of everyday tools, as though Mann is returning man to a primitive state before the world of data and technology became the guiding force. Hathaway gets the upper hand, and walks away in perhaps Mann’s most optimistic ending.

4. Thief (1981)

The OG Mann, Thief introduced audiences to this true-crime loving director who focuses on characters that take pride in the work they do, sometimes fall in love in the process, and live life on their own terms.

For expert safe-cracker and straight-talker, Frank (James Caan), he embodies the above perhaps more than any other character in Mann’s oeuvre. It might be because this is Mann’s most contained film in that it isn’t made up of major set pieces and crowded settings, but instead allows Caan to revel in the dialogue and the weight behind his words.

Thief is about a man on a mission to tick off his checklist of wants before cashing out. It’s also about a man refusing to bow down to the interests of others, instead taking it upon himself to shape his own destiny at any cost.

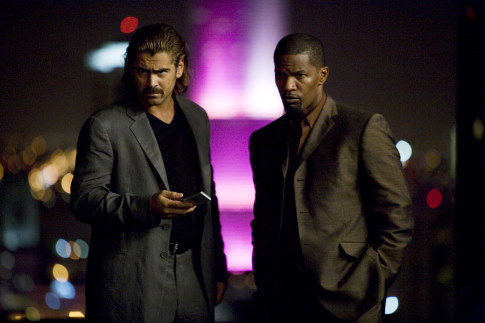

3. Collateral (2004)

Two guys in a car, strangers to each other, both operating on a routine, a structure that they rarely break from, moving as one through the luminous L.A. night but to different ends.

Collateral is a wonderous neo-noir that pivots two men with differing moral compasses against each other: Max (Jamie Foxx), a slave to his inhibition, to his failure to act and make a difference to his life; and Vincent (Tom Cruise), a man untethered, a multi-faceted nihilistic hitman who gets in, gets out, and keeps moving forward.

Much has already been written on Collateral, from its vivid imagery to the rawness of its digitised look — at once enticing and haunting. Vincent poses a threat to Max’s idealised vision of tomorrow, but also an opportunity to start making things happen and not idle by.

2. Heat (1995)

What does one even say about what, in the eyes of many, is Mann’s magnum-opus?

Heat is the sum of many parts, but it doesn’t work without its two key pieces: Al Pacino and Robert de Niro. The duo, reunited together on a feature for the first time (and for the first time ever in the same scene/s) since The Godfather Part II (1974), Pacino and de Niro are two sides of the same coin.

Vincent Hanna and Neil McCauley are like yin and yang — they don’t mix but they can’t function without one another. This speaks to Mann’s wider commentary on good vs evil, crime vs order which has been the focal point for 90% of his oeuvre. In Heat, Pacino and de Niro accentuate Mann’s fascination with these binary opposites to their full extent.

It’s as though these characters revel in the chase, of being the hunter and the prey, and they treat it like a drug that supersedes everything else in life. Mann brilliantly captures this through bright neon lights and the wider city which acts as its own sanctum that gives weight to the chase. Nothing is as beautiful as the city lights in a Mann film where cop cars race down the freeway in a storm of intensity.

But Heat is also made up of moments: the diner scene between Neil and Vincent is one of the greatest moments of character interaction in cinema history as these two men come face to face, pause the chase, and acknowledge each other; the downtown LA shootout where Mann shut down multiple blocks to shoot one of the most jaw-dropping scenes in any film ever; and the poignant finale where the two leads lock horns for the last time.

Without Heat, we may never have had The Dark Knight (2008), and that’s just one extra reason to watch this if you haven’t.

1. Miami Vice (2006)

I’m sure Miami Vice is a top-three Mann on anyone’s ranking of his work, but this bustling neo-noir about two under-cover detectives goes beyond the 80s show of the same name to become a gripping tale of people accepting that they’re living on borrowed time and learning how to manage the time they have left.

On the surface, Miami Vice is a buddy-cop thriller about two detectives infiltrating an offshore drug operation where they act as the middle-man between the international supplier and the local Miami buyer. Their mission is to find out who the buyer is, but the deeper they find themselves in the operation, the more they realise they’ll never have an opportunity like this again.

Jamie Foxx and Colin Farrell are the two leads here and (while already the case with Foxx) they instantly fit the Mann-model of characters who don’t always play by the books, are good at what they do, and sometimes make rash, emotionally led decisions.

But it’s through Mann’s ability to capture the fleeting nature of life, the suddenness of a bust and the shootouts that ensue, where Miami Vice makes a case for his best film. There’s a dream-like tranquillity to the use of digital footage here that might just be the best example of creating evocative images in the digital format. From the bright hues of the nightlife and its clubs to the more intimate sensual moments, there’s a sense of liveliness and temporality mixed together in the film’s visual language.

Mann’s growing fascination with the commodification and expendability of the human body really started gaining momentum here as well. Whether it be in the film’s final shootout where bodies drop at a whim or the use of people as shields for getting what you want (drugs, cash, obedience), it’s an aspect of his films that really does speak to how precious those moments of human interaction are for his characters when they do have them.

Empire of Light is Less than the Sum of its Parts

The Oscar-bait film too contrived even for awards voters, Sam Mendes’ follow-up to the acclaimed war film 1917 (2019) Empire of Light (2022) is a flat ode to the theatre made by some of the best industry professionals. Spanning the early 80s in the small British seaside town of Margate, we follow the workers of the quiet movie theatre including deputy manager Hillary (Olivia Colman), manager Donald (Colin Firth), projectionist Norman (Toby Jones), and bright-eyed new crew member Stephen (Michael Ward). We are mostly locked onto the world of Hillary, a depressive older woman burnt out and fading through life until a romance is sparked with the much younger Stephen.

Made with the best intentions with a world class crew and ensemble, Empire of Light stumbles not just in its underbaked racial and political underpinnings, but in its narrative contrivances that permeate every moment. Hillary is written into a dead end within 40 minutes, sucking the air out of the film before it even gets going. Mendes overreaches in so many narrative directions that no one moment is given the time it deserves, reducing everything to its thinnest ideas, making all the plot machinations nakedly visible.

There are many films inside this one, making it feel closer to a debut Sundance feature from an upstart filmmaker that is unsure whether they will ever make another film. Through its flat characters spouting unfelt political statements, Mendes has made a unmemorable film that takes for granted its extraordinary crew.

And enough cannot be said about the crew involved here; Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross craft an interesting piano score that unfortunately never seeps deeply into the drama; greatest living cinematographer Roger Deakins has mastered his craft to an absurd degree that we should be thankful doesn’t get relegated to a TV screen just yet; the ensemble of Colman, Firth, Jones, and the breakout of Michael Ward is punching well above the script, finding emotional depths to their characters that were clearly underdeveloped on the page.

One of the best technical filmmakers working, Mendes has always been successful when working with quality screenwriters (Skyfall, Jarhead, American Beauty if that’s your thing) while still pursuing his own point of view, often surrounded by top-tier craftspeople. He has been able to create quality features without working as the screenwriter, but was clearly emboldened by his original screenplay Oscar nomination for 1917, a film that is effective more as a set piece art installation than as a work of screenwriting, to pen his follow-up feature.

Much has been made about Empire of Light being a love letter to the theatre, which is reductive at best. This film is as much a movie about the movies as Snowpiercer (2013) is a movie about trains. Cinema has enough love letters to itself, but too few ones of quality and substance that values the audience on the other end of that beam of light.

The racial politics of the film are tired and dated, with the anti-black violence made in service of a white character’s emotional development that is a disservice to both performers. The few instances of racialised violence do not even give Ward the respect of a reaction shot. There is also the issue of the depiction of Stephen’s mother Delia (Tanya Moodie) in the film, a character who does not speak to her son for almost its entirety, having more lines of dialogue with Colman than Ward. Mendes shows little maturity to handle these racial aspects of his film, souring any goodwill in its pursuits of bringing to light the racism of 1980s England.

Colman does better than any actor could with her extraordinary mix of subtle rage, but the script lends her or the other actors little assistance. Her performance in 2021’s The Lost Daughter (which she should’ve won an Oscar for last year), is a better demonstration of her quality at playing a depressive older woman.

Ward’s performance as Stephen is above the level given to him, as a purely contrived character that is more aggressively attached to the film’s writing faults and poor writing than any other character. Even with the quality of individual performance from Ward and Colman, the pair’s growing romance never garners genuine interest or stirred emotions as it is just another one of Mendes’ undercooked ideas in a film without a strong perspective.

Mendes never trusts his actors and, to a greater self-critique, his own penned characters, to develop the story and romance organically, ending up with a collection of contrivances. Empire of Light is a beautifully shot but unsubstantial feature that will quickly be forgotten, adding up to less than the sum of the parts with its top-tier cast and crew.

Empire of Light is in theatres now.

Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania is the Most Inventive Marvel Film in Years

Marvel (by way of Star Wars and Rick and Morty), the surprising third instalment in the Ant-Man franchise, Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania (2023), is one of the most enjoyable and cohesive Marvel films in years, and a great entry point into the new Phase of the universe. With a wildly inventive world that enchants and inspires awe, Quantumania manages to create something that’s been lacking from Marvel of late: pure imagination and efficient storytelling.

Quantumania kicks off with a return to the Lang family. Scott (Paul Rudd) is touring his ant-pun-filled memoir; Hope (Evangeline Lily) is running the company to improve many noble causes from affordable housing to environmental rehabilitation; Hank (Michael Douglas) and Janet (Michelle Pfieffer) are reunited and retired; and Cassie (Kathryn Newton), now 18, is getting arrested protesting the police for tearing down displacement camps. The surprising heart of the film, Cassie both sparks the plot by creating a beacon to the Quantum Realm, as well as the thematic (socialist uprising via ants combats tyranny in a blockbuster? A+) and emotional story that is never beholden to other properties. The speed in which we are thrown into the world is appreciated and economical, especially in comparison to recent superhero films that have felt bloated and undercooked.

The Rick and Morty-fication of Marvel is complete in Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania, with longtime comedy writer Jeff Loveness (Jimmy Kimmel Live, Rick and Morty) given sole screenwriting credit here. Previous Rick and Morty writers landing at Marvel include Jessica Gao (She-Hulk: Attorney at Law), Michael Waldron (Loki, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, Avengers: Secret Wars), and Loveness. This connection to the cult TV show is felt particularly through its world-building and humour, as Loveness and Reed are clearly having a blast creating these unique quantum aliens, from snail horses to amoeba buildings and freedom fighters, all with a visual and comedic flair that feels considered. The parallel is also felt in its storytelling, as Loveness is able to craft an efficient and entertaining film that works independently of its outside world, maintaining a coherent thematic pull with compelling characters that feel genuinely changed through the experience.

Fears were rising that, with the emergence of the multiverse and glut of recent Marvel products, regular movie fans would be left in the dust. Thankfully, Quantumania is a refreshingly standalone film and a great entry point for this new phase of Marvel. The briskness of the storytelling allows you to get swept up in the world-building and creature design, sharing the sense of wonder Scott and Cassie have for the Quantum Realm. We are shown many sides to this new realm, from its refugee camps to its high society bars inspired by the Star Wars cantina (I was shocked not to have an original tune playing when they entered the room), all fully realised. The craft and consideration here are leagues ahead of recent entry Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022), where the biggest leap in the boundless opportunity of multiversal storytelling was an Earth where green means stop.

Director Peyton Reed, hot off helming a couple of great episodes of The Mandalorian, returns to complete his highly improbable but all-enjoyable Ant-Man trilogy. The list of directors crafting a full trilogy is short, with Reed joining Spider-Man directors Sam Raimi and Jon Watts on the superhero trilogy front. Through a consistently robust supporting cast, the Rudd-helmed franchise has always felt light on its feet and affable, mirroring its star.

Reed’s Ant-Man films thrive more in the conversational moments, both in comedy and tension than when action is required. Early entries allowed the action set pieces to play out like big-budget Honey I Shrunk the Kids (1989) homages, but in Quantumania, the action feels taken straight from the Marvel assembly line, with its rapid cuts, poor blocking, and hand lasers. Fortunately, Reed seems aware of these shortcomings, as the film does not rely on these moments for its crescendos, opting instead for more personal battles against Kang the Conqueror.

Jonathan Majors, the greatest recruit into the Marvel acting army thrives as the ominous but deeply felt villain Kang the Conqueror. Acting alongside Michelle Pfieffer for many scenes, Majors uses his physicality and always surprising depth of feeling to keep Kang more interesting and compelling to the audience, allowing him to balance out the film in ways we rarely see in Marvel villains. There is a tension and friction to his scenes that allows other actors to occupy space to play off of Majors, instead of merely dominating every moment of screen time, a rare gift to be used in a blockbuster film. The next Avengers film, Kang Dynasty (2025), is more likely to match the quality of Endgame with the emerging A-lister at its core.

No one would’ve imagined back in 2015 that Reed and Rudd would be completing a trilogy of Ant-Man films in 2023, with the third entry becoming crucial to the wider Marvel project with the emergence of Johnathan Majors’ Kang as the next Avengers villain (Loki appearance notwithstanding), let alone creating one of this quality. While still overfilled with messy CGI action set pieces, Quantumania thrives in its inventive world-building, with an economic and satisfying script by Loveness that allows its impressive ensemble to shine.

Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania is in theatres now.

Skinamarink is a Childhood Nightmare Shot on VHS

Early contender for the strangest and most fun internet explosion curio in film circles of the year, Skinamarink (2022) is an atmospheric, extremely lo-fi creepypasta horror seemingly born out of a haunted VHS tape. This may be the hardest film to have a blanket recommendation for due to its upsetting atmosphere centred around young children, durational cinema tendencies, and an active refusal to follow cinematic conventions that will annoy many audiences. It may be easier to recommend Skinamarink to lovers of Apichatpong Weerasethakul or Chantal Ackerman films than horror fanatics looking for a low-budget thrill, a place I sit on both ends of.

The filmmaker, Kyle Edward Ball, has been making horror short films for years based on user-submitted stories about their nightmares on YouTube. There is a simplistic effectiveness to many of these videos, with a certain aesthetic formed that grew into Ball’s debut feature, Skinamarink.

Set one night in a family home, Skinamarink follows two young children, Kevin (Lucas Paul) and Kaylee (Dali Rose Tetreault), who have seemingly been abandoned one night as their father disappears without a sound. This childhood nightmare of abandonment is immediately heightened as the doors and windows to their home also begin to disappear, and there is a distorted voice seemingly coming from upstairs beckoning them.

The effectiveness of the film’s horror is its depiction of a universal childhood fear shown from an actual child’s perspective. Ball is tapping into primordial fears that dwell within all of us, using the constraints of his very modest budget to heighten the atmosphere of dread across its extended run time. The film is certainly too long for its narrow scope coming in at 100 minutes, but when Skinamarink is working, it is one of the most effective horror experiences in years.

What has allowed Skinamarink to explode as a curio of indie horror cinema (including several in-demand screenings at The Astor Theatre and Palace Cinemas) is its experiential, durational cinema-styled horror that has a clear lineage in the genre, whilst feeling entirely new. Think Paranormal Activity (2007) but with actual aesthetic choices and storytelling ideas. Those films had some good scares scattered throughout the franchise, but the flat filmmaking in the name of realism makes them a chore to get through. The mixture of base human fears with an individual cinematic style that heightens digital noise and extremely low lighting, allows Skinamarink to feel familiar yet new, creating a deceptively compelling horror.

Its weaponisation of digital distortion is pretty special while still feeling familiar, turning one of indie cinema’s biggest issues (access to only cheap equipment), into its greatest strength. At its strongest moments, Skinamarink will have you questioning your own eyes, not sure if you’re seeing something that is not there or if Ball is manipulating everything on screen. Establishing an off-kilter immersion from the outset allows you to never be sure of that answer, drawing you further into each scene and the encroaching feeling of dread.

Ball gives us just enough narrative to get a sense of the family dynamic here before this fateful night. In a film centred around parental control, beginning with the four-year-old child Kevin apparently falling down the stairs (an act, like many in the film, we do not see but only hear) sets an early tone and has us questioning the children’s parents. The oldest child, six-year-old Kaylee, not wanting to speak to the mother further layers the themes of domestic issues and how they play a role in our childhood fears. In a regular horror film, a disembodied voice beckoning you to “come upstairs” would regularly have you questioning why our young protagonist would do such a thing, but here, we have an understanding about the likelihood this situation isn’t too far removed from their previous experience.

Its central set piece, which involves Kaylee going upstairs into her parent’s room, is one of the most haunting film sequences in years. After 40 minutes of atmospheric buildup, completely unsure of where we are being led, you will be wishing to return to watching cartoons downstairs and staring at Legos. The extended long take in this scene ratchets up the tension to a boiling point, with your palms a sweating mess in a sequence that seemingly goes for eternity. This is no doubt the peak of the film, with only smaller moments in the proceeding hour that match its tension and atmosphere. Structurally, Skinamarink could’ve taken some notes from its predecessors Paranormal Activity and Blair Witch Project (1999), by peaking in its final moments, but the atmosphere is definitely more of the Ball’s focus than the bigger scares the film has. Unfortunately, this makes the film drag in its second half, even for a great lover of durational cinema as I am.

A film sure to annoy and entice in equal measure, Skinamarink is a curious and mostly effective piece of atmospheric horror filmmaking from an interesting internet-focused filmmaker that is able to use his constraints to his advantage. Whilst not of the same quality as The Blair Witch Project, or the level of engagement culturally so far, Skinamarink is a more interesting and worthwhile horror experience than almost any found footage-style films in the genre.

Skinamarink is on Shudder now.

Babylon Is A Frenetic Fable on Silent-Era Hollywood

The only story more common in Hollywood than a film about filmmaking is an award-winning director cashing in a blank check to make a dream project they may never get the chance to do again. Babylon (2022), the new film by Oscar-winning director Damien Chazelle, is an all-in movie for a filmmaker who knows the opportunity to make a big-budget, silent-era Hollywood romp with A-list stars will not come around again. We should be grateful the prodigious filmmaker chose to use seemingly every ounce of industry capital he had to get this oddball movie made, as even if the film isn’t great, there are enough transcendent moments, particularly early on, that makes it a ride worth taking.

Inside this whirlwind of frenetic Hollywood excess is a group of artists striving for their place in the moviemaking circus as it begins to transition from the silent era into the talkies. These include the star-to-be Nellie LaRoy (pitched to eleven Margot Robbie); a hustling upstart looking for his place in the movies and true heart of the film, Manuel Torres (Diego Calva); and ageing star with a waning grip on the top, Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt); including a suite of other terrific performers in this frenetic tragicomedy that you won’t soon forget.

Calva is wonderful in the film and a true revelation, but the standouts for the film are Li Jun Li and Jovan Adepo, who play singer and artist Lady Fay Zhu and jazz trumpeter Sidney Palmer respectively. Both characters are great in limited time, but even in a film of this width, their stories are sidelined too easily. There are essentially four films worth of story in Babylon, from Manny and Nellie’s rise, to Palmer’s rise in the industry that does not value him, to Lady Fay’s weaving through a constantly changing industry without the recognition she deserves, to finally Jack Conrad’s slow decline from the heights of stardom into irrelevancy. All these dense stories deserve more time than they are given, sidelined in favour of ambitious dalliances into the debauchery of the industry Chazelle seems so persistent to explore.

Surprisingly, given the long runtime, Babylon is stretched thin by its wide array of storylines. Jack’s story rarely interweaves with Nelly and Manuel’s, making them feel isolated. Chazelle’s previous films, Whiplash (2014) and La La Land (2016) work emotionally as two-handers between the leads, whilst here the key characters are oftentimes isolated from each other, striving for their own ambitious goals alone in a chaotic world. This is clearly by design, as Jack’s declining trajectory works alongside his divergence from the young upstarts who are looking to take over the budding talkies boom, but the film ultimately falters because of it.

Where Babylon never falters is in the deliriously bombastic score from Justin Hurwitz, which will no doubt pick him up another Oscar. This may be his crowning achievement as a film composer as Chazelle allows him room to dominate. Full of bombastic horns and drums that propel us into each scene with boundless energy, Hurwitz is the shining light in an uneven film with easily the year’s best score.

A surprisingly dark film visually, with Chazelle and cinematographer Linus Sandgren opting for a more natural use of lighting which heightens the dynamic contrast between the debaucherous night sequences and the bright daylight where the work gets done. This is most effective through the opening two sequences from the coke-fuelled bacchanalia prologue into the extended scene of manic moviemaking. It is clear this is where Chazelle finds himself most comfortable and where Babylon truly shines. Watching Manuel organise a mass of skid row extras for Jack’s war film or Nellie’s first day on set is electric, set to Hurwitz’s bombastic score, all within the ticking clock structure of the single day shoot, is one of the best sequences of the year. While I am always in favour of directors taking big ambitious swings when given the opportunity, there is a tinge of sadness that Chazelle moves away from these high points later in the film.

Chazelle has always been a filmmaker who wears his influences on his sleeve, which has been felt in the past, with Whiplash and of course La La Land, like a prodigious young filmmaker attempting to brush shoulders with both modern and canonical directors simultaneously. Here, the Oscar-winning director is working to rewrite the legendary Singin in the Rain (1952) as a tragicomedy structured somewhere between Scorsese classics Goodfellas (1990) and The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), or Paul Thomas Anderson’s braggadocio Hollywood epic Boogie Nights (1997). This is a lofty goal that is certainly appreciated, even if it doesn’t hit the mark consistently.

By wielding PTA as a key inspirational pole instead of the Boogie Nights director’s idol Robert Altman, Chazelle is playing a game of telephone with this style of film, ending up with a story with smoothed-over edges. Scenes of freneticism are shown cleanly, never feeling dangerous to the audience or its key players. Nellie and Manuel glide through manic scenes as smoothly as Sandgren’s graceful camera, creating a certain inevitability to their landing point that while interesting as a decision, ultimately flattens most defining sequences.

There are thematic depths to mine in Babylon, but they feel oftentimes short-changed in favour of larger set pieces. Manuel’s narrative of assimilation and identity is compelling and the most consistent thread being pulled throughout this 188-minute cinematic feast. We follow this immigrant story of a man who must essentially remove his nationality in pursuit of his ambitions within a rigid Hollywood system. Total annihilation of personhood for your art is something that clearly compels Chazelle as it is a key driver for his characters across his filmography, but it is here with Manuel that these themes truly land. We see him transform throughout the film, shifting into whiter clothing, changing his name to Manny more diligently, and even telling producers that he is Spanish, all in the hope that it gets him closer to his goal.

What separates PTA’s writing from Chazelle’s is ultimately what is lacking in a garish epic like Babylon: romanticism towards its characters. This does not mean fawning over them but treating them with respect and humanity that allows us to connect with them. Chazelle too often uses his characters as vessels for obsession and ambition in a primordial sense, making them kinetic and engaging, but rarely emotionally involving. The most personal moment of the whole film is wedged between its two great opening set pieces, as we see the modest living arrangements of Nellie and Lady Fay after seeing them command the attention of the lavish Hollywood party through their powerful charisma.

Chazelle has made a career of crafting sequences with wide dynamics, thrilling highs hard cut into crushing lows that usually work wonders like in Whiplash and La La Land. Unfortunately, adding to its issues with being stretched thin, these dynamics end up compressing the emotionality into dust.

The anguish-laden death march that consumes much of the second half sucks all air and exhilaration from the theatre, so the film is unable to coast off his own momentum as it languishes to its finale. This total fever dream opening into a death spiral has been done to great effect before (Boogie Nights and Goodfellas), but in Babylon the work on characters is less involved on a human level so the feeling is widely cheapened.

Ultimately, Babylon feels like a terrarium of meticulous detail about a revered moment in Hollywood history, with the edges sanded down to create a smooth glass dome. Even its finale, which is attempting a Godard-esque swing for the fences, feels strained. Authenticity was not the predominant goal of the film (this is not 2009’s The Artist but with coke), but somewhere along the way, the heart of the film was sidelined in terms of gawking ambitious set pieces. There are incredible sequences here that will be burned into my retinas to the tune of blaring trumpets, but you may not feel anything at the end.

Babylon is in select theatres now.

Best of 2022: Arnie’s Picks

Picking out any 10 films from a year with stellar titles is never an easy task; this was especially the case for my 2022 list. In fact, not since 2017 have I had to think as much about the films on my end-of-year list. From David Cronenberg’s return to directing almost eight years since his last feature, to James Cameron’s return to Pandora almost 13 years since Avatar, right through to Tom Cruise’s return to the character that propelled him to A-class status — there was no shortage of the epic, iconic and memorable. That’s just a snippet of the below, so here’s my best 10 films of 2022.

10. Crimes of the Future

Having not directed a film since Maps to the Stars over eight years ago, David Cronenberg’s latest, Crimes of the Future, sees the body-horror mastermind return in resounding fashion.

The film, which I view as one of the dark-horse titles on my list, delivers all the signature Cronenberg goodies that audiences love (blood, guts and more guts) but in a much more toned down display. Of course, Cronenberg never does gore for the sake of it, but instead explores mankind’s deepest rooted fears —experiments gone wrong, tech turning on us etc.— while using the grotesque to amplify his concerns.

Crimes of the Future is no different in that regard, as it looks to a time ahead where humans have a changed digestive system and a hunger that can only be fed through the likes of plastic. Performance art meets the grotesque, with Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen) growing organs almost at a whim, and his partner in crime, Caprice (Léa Seydoux) removing them to a much appreciative audience.

Howard Shore’s hauntingly subtle score gives weight to the eeriness at play and even heightens Mortensen and Seydoux’s already brilliant, nonchalant performances. It’s a film that’s creepy but clever in its creepiness, one that captures the festering of the human body and the need to adjust the way we live as our bodies change. That’s only part of it, of course — the real crime is not watching the latest Cronenberg.

9. Hit the Road

There’s few films in 2022 that will throw you an emotional curveball like Panah Panahi’s Hit the Road. Panahi, son of legendary Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, crafts a road trip story that explores the struggle of separation, something that is a staple of Iranian filmmaking and a harsh reality in a country with a turbulent political standing.

Politics aside, the film is peppered in the humour often found in similar works from the region —Jafar Panahi’s, in particular— as it incorporates everyday family bickering and banter that I’m sure everyone who has ever been on an “are we there yet” type road trip with their family, has experienced. Films like this often require a convincing ensemble to help hit home that tense but loving family feel, and fortunately the ensemble here do an excellent job.

8. Kimi

A covid-era film that doesn’t make covid its main story point? Count me in.

With an overlooked performance by Zoe Kravitz who nails the agoraphobia-isolated character with her very blank, “leave me alone” facial expressions, Kimi sees Steven Soderbergh pack a lot of nuance into this smaller-scale crime-thriller. The result is a nail-biting search for answers as Angela Childs (Kravitz) is forced by circumstance to venture outside after hearing what she suspects is a sexual assault or a murder, on the Kimi device (this film’s equivalent to Amazon Alexa).

Obvious comparisons have been made to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), though the films are entirely separate in how they approach their subject matter.

7. The Batman

Matt Reeves’ The Batman represents a fresh take on the caped crusader, one that is more akin to the ‘Arkham’ video games in that it explores the Batman’s more detective leanings.

What follows is a crime-thriller worthy of the highest praise and one that is reminiscent of the likes of classics in the sub-genre including Seven (1995). Greig Fraser’s cinematography is wonderous and keeps in line with the very gothic leanings that Reeves is going for here. Michael Giacchino’s score is equally inspired, with the composer using church bells and low hums to create an eerie sensation.

Reeves no doubt looked to the Christopher Nolan and Tim Burton’s films when figuring out how he would approach this, and there are obvious correlations like the gothic-vibe from Burton’s films and the development of the Riddler being very similar to that of the Joker in Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008). Yet, this film is unequivocally Reeves’. Sure he drew on the films that came before his, but this is a film made up of close-knit conversations, measured action sequences, and clever storytelling. The rowdiest this film gets is during a truly memorable chase sequence involving Batman’s custom V8 Batmobile.

The cast is just as committed, with Robert Pattinson’s emo-like appearance being fitting for the darker aesthetic; Zoe Kravitz once again fits the part perfectly playing Catwoman; Collin Farrell shines as Oswald Cobblepot in what has been a stellar year for him; and the likes of Paul Dano and Jeffrey Wright do well in their parts as well. In fact, all aspects of production come together brilliantly like cogs in a machine. The end product is a welcome addition to the ever-growing Batman story.

6. Jackass Forever

When it comes to practicality in filmmaking, Johnny Knoxville and his crew of misfits are the ones you can count on to put on a show.

Jackass Forever is a film nestled in its own comfy corner of cinema. Yes, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin and Jackie Chan are incredible actors and stuntmen who have put their bodies on the line for the sake of entertainment, but it’s the man-child Jackass group who have done it because they find it fun to face death.

Yet, Jackass Forever isn’t just people doing things that are best left to the imagination, it’s also a culmination of 20+ years of commitment to pushing the boundaries of what can be done in front of the camera. For all of its death-defying moments, Jackass Forever feels like a warm hug that throws you a sucker punch when you’re least expecting it. Bringing in the classic faces that have laid the groundwork for Jackass, along with some new and equally risk-embracing ones, this is a film that celebrates the unimaginable, and doesn’t hold back on the bruises.

It’s a film, like the others in the series, that is built up of ‘firsts’ both in terms of what you’re seeing and for the cinema broadly, and deserves the highest of praise for what it achieves.

5. Ambulance

You either love him, hate him or tolerate him, but there’s no denying the Michael Bay is a man of the cinema — particularly action cinema.

Ambulance, like all of Bay’s previous films, is set on displaying the biggest and wildest action sequences you can get. The film hits like a heavy dose of adrenaline, and it keeps you infused right from its early stages until its heartfelt finale.

The film is a testament to Bay’s unabashed approach to direction where he keeps the tension boiling, turns up the temperature gradually, and then drops the heat to a boil again while never turning it off. The best examples of this are found in the way the film’s technical elements work together to sing Bay’s chaotic tune: the piercing score, the snappy cross-cutting, the canted camera angles, and the mobile drone camerawork that takes the audience and positions them in unfamiliar situations.

Ambulance works because even with all the absurdity leading up to the characters finding themselves in this dire chase situation (let’s face it, no one would escape that many LAPD officers and vehicles), there’s never any respite to dwell on that aspect of the film. Bay knows what he’s doing and you can either buckle up for the ride, or dive ride out the passenger seat.

4. The Banshees of Inishiren

In what is quite clearly a spiritual successor to McDonagh’s equally witty and heartfelt debut feature In Bruges (2008), The Banshees of Inisherin paints a perplexing picture of the human condition against the beautiful backdrop of a fictional Irish town during the Irish Civil War.

It’s a story of two friends —Colm (Brendan Gleeson) and Pádraic (Colin Farrell)— who decide not to be friends anymore (well, at least one of them decides). But more than that, The Banshees of Inisherin is about the fleeting nature of life; the realisation that nothing lasts forever even if we want it to.

McDonagh’s script here is easily his most realised — even if In Bruges still contains some of my favourite lines from any movie ever. He manages to mesh together humour and poignancy in ways that no other director does, and it leaves you in a state where you’re not sure whether to laugh, cry or both.

Gleeson and Farrell are at the top of their game (as is the rest of the cast), and I wouldn’t be surprised if we see the male acting categories be swept up by this duo in the coming awards season.

3. The Fabelmans

Anything I say about Steven Spielberg is superfluous at this stage, and honestly if The Fabelmans is anything to go by, Spielberg tells (or shows) you everything you need to know about him anyway.

This is ultimately Spielberg’s visual diary, one that at once examines the very youthful promise of endless possibility —with the only limitations being your imagination (as symbolised by the camera)—, and the navigation of expectation, of the un-imaginary and the tangible (the reality that hits when the record button is turned off).

It’s clear that Spielberg and co-writer and frequent collaborator, Tony Kushner, have dug into the nitty gritty of the directors’ life. There is a level of verisimilitude coursing through the film whether it be in the performances, the very raw and grounded screenplay that avoids glossiness, or John Williams’ moving score — the duo have cashed in all of the chips Spielberg has accrued and pulled no stops.

The Fabelmans paints an interesting portrait of self-actualisation, of finding your place in the world and pursuing what you love even if it means confronting hard truths in the process. This is Spielberg’s world, and we’re living in it.

2. Avatar: The Way of Water

No one does blockbusters quite like James “Jim” Cameron, and Avatar: The Way of Water is the proof in the pudding.

The Way of Water takes audiences to the far beyond of Pandora, namely to its oceanic vistas that, on their own, make the 13 year wait between the original and the sequel all the more worth it.

Cameron, of course, is no stranger to pushing the boundaries of what is achievable at such a scale; if a project isn’t ready to be pursued, be it because of a lack of technological development or the moment just not feeling right, he won’t pursue it. That was the case with Avatar (2009) which he decided to eventually make almost a decade after writing the treatment. He saw Peter Jackson’s development of motion capture with Gollum in The Lord of the Rings films and King Kong in King Kong (2005) as turning points for technology in cinema, as well as Davy Jones in Gore Verbinski’s The Pirates of the Caribbean films.

But The Way of Water blows all of these titles out of the water with what it achieves visually (and that’s coming from a died hard Jackson and Pirates fan). From the refined look of the Na’vi including the way they move under water and their human-like movement generally, to the bumped up frame rate at 48fps which adds extra fluidity to proceedings — The Way of Water is a visual masterpiece that represents a pivotal turning point in visual effects and motion capture.

Aside from its technical marvels, it’s also a sum of all of Cameron’s experiences up until now. His brilliance ultimately rests in his unmatched understanding of scale — of how to get all of his story points in a basket while showcasing them in the biggest way possible.

He clearly cares for this world and everything within it, and he pours his heart and soul into each and every frame to the point where you can’t help but care for it as well.

1. Top Gun: Maverick

Do you feel the need for speed? I sure did.

Top Gun: Maverick is the Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) of 2022. The perfect sequel to Tony Scott’s iconic Top Gun (1986) and one that goes above and beyond its predecessor in (almost) every department (save for maybe how iconic it is, though we should maybe give it 36 odd years).

Joseph Kosinski’s film is the one that I’ve though about the most throughout 2022, so much so that I’ve been desperate to buy its original poster which has now ignited a fascination with poster collecting that I never knew existed.

Whether it be the death-defying air-scapades that prove how much of a madman Tom Cruise truly is, or the care with which this sequel is able to revisit and reimagine its titular character — there’s no shortage of brilliance behind every decision. The stakes are raised, and Maverick is forced to come to terms with his past, find his place in the world, and pass the torch on to the younger generation — directions in characterisation that screenwriters Ehren Kruger, Eric Warren Singer, and frequent Cruise-collaborator, Christopher McQuarrie, do a great job of balancing.

This film will make you nostalgic, will leave you in awe, and will sit with you long after its end credits roll by.

Honourable Mentions: Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery, Ticket to Paradise, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, The Northman and Good Luck to You, Leo Grande.

The Fabelmans is a Surprisingly Thorny Origin Tale

Pauline Kael in her legendary review for Steven Spielberg’s pre-Jaws (1975) breakout feature The Sugarland Express (1974), a film she called “one of the most phenomenal debut films in the history of movies”, that Spielberg “isn’t saying anything special in The Sugarland Express, but he has a knack for bringing out young actors and a sense of composition and movement that almost any director might envy.” This note encapsulates the pantheon filmmaker’s now long-serving skill set and potential flaws as an empty escapist entertainer (a critique Spielberg agreed with as something he had to grow into).

This should be kept in mind while watching his most personal film yet, The Fabelmans (2022), both in following our budding protagonist’s journey as a filmmaker, but also in Spielberg’s own journey behind the camera to arrive at a place where he felt daring enough to put his life on screen in this openly vulnerable way.

The film follows Sammy (Mateo Zoryan as young Sammy, Gabriel LaBelle as teenage Sammy) and the family Fabelman from a child to 18, tracing the journey from New Jersey, to Phoenix, and finally to California as he discovers his love for film. This love, however, begins to complicate as Sammy grows more invested in cinema, an investment that intertwines and impacts his love, both internally and externally, for his family.

The opening scene is a microcosm of the film, with Sammy and his parents Mitzi (Michelle Williams) and Burt (Paul Dano), going to a showing of Cecil B. Demille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (1952), his first film experience. Sammy is scared to go in, with Spielberg opening the frame from his perspective, with his parents’ legs looming over the screen like Charlie Brown adults, so the pair do their best to reassure their child in their own ways. Burt believes this can be achieved by explaining to Sammy how the projector operates on a mechanical level, while Mitzi rebuts by expressing to him that “movies are a dream”. This duality plays throughout the film, with Spielberg with Sammy as his stand-in, as a budding craftsman that has the soul of a big-dreaming artist.

On its surface, The Fablemans has the appearance of the ultimate final Spielberg film. In a half-century-long career, the legendary filmmaker is looking back at his upbringing, mining the depths of his childhood to create a truly individual coming-of-age story that he has more than deserved to make. Whether intentional or not, Spielberg has created an aura around The Fabelmans as the film he has wanted to make his whole life and feels may not get another chance besides now. There is an urgency to the storytelling that creates propulsion from scene to scene. Spielberg is the ultimate sentimentalist filmmaker, but this may be his most naked and open-hearted. Surprisingly though, the film is a more biting reflection on one’s upbringing as a young artist than it is perceived and is a truly unique film experience by modern Hollywood’s most important filmmaker.

The film has a truly fascinating origin and is worth adding an extra chapter to the documentary Spielberg (2017), with the filmmaker shifting his focus during Covid, which forced West Side Story (2021) to delay a year, and for his children to be at home with him in lockdown. He also began working on this film shortly after his parents passed away (his father living to 103!) which should be noted in the context of the film. The pandemic is a large reason for this glut of memoiristic films by seasoned veteran filmmakers, with Spielberg being no exception. And, to no surprise, the master filmmaker has made the best film of the class.

Divorce is a defining aspect of Spielberg’s career so depicting the ur-separation that defines him is deeply compelling. Family units being separated can be seen throughout Spielberg’s filmography, from E.T. (1982), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Catch Me if You Can (2002), A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), all mining from similar experiences and placing them inside of other stories. In the Fabelmans, his relationship with his family changes and shifts in interesting and messy ways, especially in relation to his obsession with the camera and the power he wields in it. Seeing Sammy be oblivious to the power and destruction that his filmmaking obsession has on his family, with the emotional journey we see him go through, eventually unravels to him by the end of The Fabelmans that with great power comes great responsibility.

Frequent writing partner Tony Kushner has discussed how he believes Steven needed someone outside of the family to help work on the script. Anne Spielberg (Steven’s sister portrayed by Julia Butters in the film) wrote a script I’ll Be Home in 1999 about their childhood that they considered making into a film but never did. Their relationship is so connected at this stage, Kushner is able to balance the necessary mix of therapeutic memoir ghostwriter, and close filmmaking partner to create a truly special film. Using Kushner’s masterful skills in humanising and empathising with each character, Spielberg is able to create an honest love letter to his parents and those that made him who he is.

The power of Spielberg’s clear-eyed and impassioned filmmaking, mixed with Kushner’s deft hand at profound characterisation, allows the audience to see themselves in every character. This is as much a film about Mitzi and Burt as it is about Sammy, with Kushner able to establish an extraordinary amount of emotional depth out of these personal stories for Spielberg whilst never feeling overly soft or cruel to their lives.

The film mines aspects of Spielberg’s childhood that were not known, as he was clearly not ready to discuss in interviews or in the 2017 documentary, opting instead to express it the only way he knows how: by putting it on celluloid. The revelations made in The Fabelmans are clearly so personal to him that it is so heartwarming and heart-wrenching to see them rendered on screen for the world to see in some of the best scenes of the year.

A personal favourite scene of the film and perhaps of the year, is the pivotal scene of Sammy deciding to show Mitzi the camping trip edit that has been eating him up and could rupture his family. Every moment of this scene is emotionally charged and perfect, leading to perhaps the most important use of Spielberg Face in his career. Beginning with a collection of insert shots, delicately showing the tactile and personal process of setting up his projector, adding to the weight of Sammy’s decision. Nothing illustrates his character more than choosing to show this film to his mother as his voice in an argument, both in his fear and his unknowing power his camera has. This moment also illustrates the evolution Mitzi and Sammy’s relationship has with these films in the closet, from humble childhood beginnings to emotionally shattering ends.

What allows The Fabelmans to expand past an individual coming-of-age story is the connection Kushner and Spielberg give to supporting characters in Sammy’s life. Woven delicately underneath the film is Reggie, (played wonderfully by Once Upon a Time in Hollywood 2019 breakout Julia Butters) and her emotional connection with her mother Mitzi. In the mother’s dress rehearsal for her piano performance, on the camping trip as the men are enraptured by Mitzi’s dance, and after the parents announce their divorce, Reggie is defending her mother, someone she is clearly emotionally in tune with while others are merely drawn to it. The Fabelmans is more than just Sammy’s story, through these other characters the film has shown a wider lens at this family as it emerges through crisis and change in an emerging America.

Biopics often fall into a trap of whipping through the subject’s life at a rapid pace, never allowing the film to ground itself in a place for long stretches, with important figures whipping through their life scene to scene. The Fabelmans has several scenes that play out that way, like the abrupt entrance of Uncle Boris (with an awards-worthy performance by Judd Hirsch), as well as a chance meeting with John Ford (I won’t spoil who he is played by) that closes the film. But there is never an air of dishonesty or hokiness to these moments, especially the Uncle Boris scene which really illuminates to Sammy his connection to his mother and their familial bond to art which is sure to lead to heartbreak.

Spielberg’s whole heart is on the screen, warts and all. What makes The Fabelmans succeed is its lack of pure saccharine while still maintaining his signature warmth. It is a crucial scene that can be put up against any of his totemic scenes, showing Mitzi and Burt sitting down with their children to tell them about the divorce, which devolves into a shouting match. While frozen by what’s happening, Sammy isolates himself on the staircase while his family sits around the couch, he sees himself in the mirror, holding a camera up to this distressing confrontation. With an audible groan coursing through the audience, this is perhaps the most critical Spielberg has ever been about himself and how he uses filmmaking as a way to both reveal and hide behind his personal life.

Pair that with the pivotal scene of the antisemitic bully Logan (Sam Rechner in a quietly brilliant performance) confronting Sammy after the burgeoning filmmaker decided to capture him as the golden child of the school, and we have a truly unique experience of watching a masterful artist trying to come to terms with his camera-wielding compulsions.

The Fabelmans is in select theatres from January 5th.